Blind Read Through: The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2, Túrin’s Third Tragedy

“And thereupon Turambar leapt upon the high place and ere Brodda might foresee the act he drew Gurtholfin and seizing Brodda by the locks all but smote his head from his body, crying aloud: ‘So dieth the rich man who addeth the widow’s little to his much. Lo, men die not all in the wild woods, and am I not in truth the son of Úrin, who having sought back unto his folk findeth an empty hall despoiled (pg 90).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we delve back into Túrin’s story and reach a turning point in his life. In addition, we get to experience Túrin’s third tragedy.

We left off last week with Túrin leaning into the Outlaw mentality and choosing that lifestyle in the woods and wilds. As we’ve discussed, Túrin didn’t have the easiest childhood. His father was a thrall to Melko, as were many of his people, and his sister died young. Mavwin, Túrin’s mother, sent him to live with Tinwelint as a ward to that Elven King. He lived with this idea of being an orphan his entire life, even though his mother lived and gave birth to another sister.

In his head, Túrin always felt as though others were looking at him as an outsider, so when he killed Orgol (his first tragedy), he assumed that others were judging him based on his family. It isn’t until he kills Beleg (his second tragedy) that he begins to think less of himself and his contributions to society, so he begins to slide into being an outlaw.

Túrin does not account for the area’s history and how Melko had corrupted things. After we find out about his outlaw shift, there is a meeting with the Rodothlim. To rally them for battle, “for he lusted ever for war with the creatures of Melko (pg 83),” he called for them to: “Remember ye the Battle of Uncounted Tears and forget not your folk that there fell, nor seek ever to flee, but fight and stand (pg 83).”

Túrin needs to take a history lesson. The Battle of Unnumbered Tears (later called in The Silmarillion), also known as Nirnaeth Arnoediad, was so named because of the sheer amount of dead and the Doom of Mandos.

Mandos laid down that curse because the Noldori killed their kin to go after Melko and recover the Silmarils. In that titular curse, Mandos tells the Eldar, “Tears Unnumbered ye shall shed,” In this battle, also known as the Fifth battle in the wars of Beleriand, Morgoth gains ground and begins to take over the land.

So, while Túrin is internalizing the wrongs of his life and turning to violence to assuage his conscience, he forgets that everything that caused the issues was because of the Noldor, not because of him or his deeds, horrendous as they are.

So Túrin leaned into his anger and spoke to Orodreth, a smith, for a weapon because he could no longer touch the sword he killed Beleg with. This creation deviates from what the story later became because Orodreth and not Eöl fashioned Gurthang.

“Now then Orodreth let fashion for him a great sword, and it was made by magic to be utterly black save it’s edges, and those were shining bright and sharp as but Gnome steel may be. Heavy it was, and was sheathed in black, and it hung from a sable belt, and Túrin named it Gurtholfin the Wand of Death; and often that blade lept in his hand of its own lust, and it is said that at times it spake dark words to him (pg 83).”

Orodreth tried to speak against fighting against Melko’s armies, regretting his creation of the Wand of Death, but Túrin was both craving war and trying to atone for his past indiscretions, so he went out and fought every agent of Melko he could find. He became infamous, and it did not go past Melko’s sight. Melko released a great army, “and a great worm was with them whose scales were polished bronze and whose breath was a mingled fire and smoke, and his name was Glorund (pg 84).”

Glorund killed Orodreth, who, even on his death bed, reproached Túrin, blaming him for the destruction his range had caused. Túrin tried to fight, but the dragon had powers Túrin didn’t understand, and the drake charmed Túrin, holding him in place, while Failivrin waws carried away, crying out, “O Túrin Mormakil, where is thy heart; O my beloved, wherefore dost thou forsake me (pg 86).”

She didn’t understand that he had been charmed and thought he was letting the creatures kidnap her.

Túrin was trapped there with the mind games of Glorund until finally, the dragon set him free, allowing him to go after Failivrin or seek out his mother and sister, whom he only knew as a newborn.

He decides to go after his mother, only to find she has fled Dor Lómin. In her place, she left a local high-class man named Brodda to watch over her estate, but Brodda, seeing the wealth to be had, rebranded all her cattle and property as his own.

Túrin had already killed, and now he had someone directly blame him for their misfortune (in Orodreth), and he chose the wrong path to find his mother, succumbing to Melko and Glorung’s deception.

It is at this point that Túrin forsakes morality. He is no longer trying to be an upstanding citizen. Even in his outlaw stage, his actions were to help and save others. It is here that we get the quote at the beginning of this essay, and it is here that we see Túrin’s next tragedy. He has given into his anger and hate, gone over to the dark side (forgive the crossover), and decided to go with full-fledged murder.

Moving forward in his story, he is still an outlaw, but he is no longer an outlaw for the good of the people. He is now an outlaw hell-bent on his emotional trajectory.

Join me next week as we continue on Túrin’s journey!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Túrin’s first tragedy

“To ease his sorrow and the rage of his heart, that remembered always how Úrin and his folk had gone down in battle against Melko, Túrin was for ever ranging with the mosst warlike of the folk of Tinwelint far abroad, and long ere he was grown to first manhood he slew and took hurts in frays with the Orcs that prowled unceasingly upon the confines of the realm and were a menace to the Elves (pg 74).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we begin to learn a bit about Túrin and experience his first tragedy of character while trying to understand Tolkien’s purpose in the themes of this tale.

Tolkien spends much of his time in this early version of Turmabar, striving to show the differences between Men and Elves (the more Tolkien created, the less he described Elves as Gnomes. It seems like he started to think of Gnomes as anything fay-like, as the moniker became a catch-all). Men tended to be less unkempt, more creatures of passion, whereas Elves were much better groomed and stoic.

Through this time, Tolkien was still developing his story, language, world, and its peoples, and these lost tales were written as an exploratory first draft to get the world out of his head and onto paper, but, as evidenced by The Silmarillion, Tolkien was not happy with these early drafts. They lacked cohesion and a thematic goal.

An example of this is as follows: “Now Túrin lying continually in the woods and travailing in far and lonely places grew to be uncouth of raiment and wild of locks, and Orgol made jest of him whensoever the twain sat at the king’s board; but Túrin said never a word to his foolish jesting, and indeed at no time did he give much heed to words that were spoken to him, and the eyes beneath his shaggy brows oftentimes looked as to a great distance (pg75).”

Túrin is a Man (as in every other Blind Read; read this as Human whenever capitalized), and Men are described as much more feral creatures. This classification was the original intent of Men, specifically because of Tolkien’s experiences in The Great War, he distrusted human instinct and saw humans as impetuous and violent creatures. Violent and feral is a very apt description of how Túrin (and almost every other Human in this story thus far) is described. He is animalistic; he “seemed to see far things and to listen to sounds of the woodland that others heard not (pg 75).” “He was moody (pg 75).”

One function of this could be because the majority of Men in these early stories that came from Hithlum were captured by Melko and held as thralls and slaves for many years, and Túrin (in The Book of Lost Tales, not The Silmarillion) is no exception, but more realistically Tolkien initially created Men this way because they were not born of the gods the way the Eldar were. Their lives are short; thus, they are much more emotional and prone to reaction because they need to feel the depths of emotion and experience much quicker than their immortal brethren.

This version of Turambar is much less tragic and much more vicious. Orgof, the Eldar we saw above who was a playground bully of Túrin, takes the place of Saeros. In the later Silmarillion version, Saeros is still a bully, but when Túrin finds him in the wilds, he turns the tide and strips Saeros naked, intending to embarrass the bully. Saeros, terrified, tries to jump a Fjord and falls to his death. This accidental death is the first event that makes Túrin an outlaw, but in this version, nearly everyone in Doriath sympathizes with Túrin and tries to get him to come back, but his conscience is what pushes him further into exile.

This earlier version is entirely different:

“Then a fierce anger born of his sore heart, and these words concerning the lady Mavwin blazed suddenly in Túrin’s breast so that he seized a heavy drinking vessel of gold that lay by his right hand and, unmindful of his strength, he cast it with great force in Orgof’s teeth, saying: ‘Stop thy mouth therewith, fool, and prate no more.’ But Orgof’s face was broken and he fell back with great weight, striking his head upon the stone of the floor and dragging upon him the table and all it’s vessels, and he spake nor prated again, for he was dead (pg 75).”

Túrin’s actions were murder in this earlier version. It was an act of a feral and impetuous being, as we should expect from any Human in these early tales of Tolkien.

To take that a step further and show the difference between Elves and Men, Tinwelint and his court show incredible understanding. “Yet they did not seek his harm, although he knew it not, for Tinwelint despite his grief and the ill deed pardoned him, and the most of his folk were with him in that, for Túrin had long held his peace or returned courtesy to the folly of Orgof (pg 76).”

Meanwhile, Túrin runs away and joins a group of people in the woods described as “wild spirits (pg76).” Again, Túrin is a Human and feeds into his animalistic tendencies. His emotions are so high that he cannot understand that there could be clemency for him in Doriath because he does not hold any for himself. His emotions again overpower him, and he runs off to the only place where he feels at home, in the forest with ruffians.

This kind of childish behavior is endemic to Men in early Tolkien, and it isn’t until the later versions (I believe The Silmarillion is either the Third or Fourth draft) that they begin to get more depth and character. The whole point of these stories evolved from being a general history of our world to actual ages of time, and this time was the Age of the Eldar. Tolkien’s main goal, however, was leading his fairy tale, through Eriol and The Cottage of Lost Play, to the fourth Age. The Age of Men.

Join me next week as we introduce one of The Silmarillion’s best characters, Beleg, and discover Túrin’s second tragic act.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Tale of Tinúviel, conclusion

“Lo, the king had been distraught with grief and had relaxed his ancient wariness and cunning; indeed his warriors had been sent hither and thither deep into the unwholesome woods searching for that maiden, and many had been slain or lost for ever, and war there was with Melko’s servants about all their northern and eastern borders, so that the folk feared mightily lest that Ainu upraise his strength and come utterly to crush them and Gwendeling’s magic have not the strength to withold the numbers of the Orcs (pg 36).”

Welcome back to another Blind read! This week, we finish The Tale of Lúthien and reveal more differences between The Book of Lost Tales and The Silmarillion.

We left off last week with Lúthien and Huan saving Beren from Tevildo and the cats. After escaping, they retreated and recovered, but there was still that everlasting desire to go and get the Silmaril back, so they devised a plan.

“Now doth Tinúviel put forth her skill and fairy-magic, and she sews Beren into this fell and makes him to the likeness of a great cat, and teaches him how to sit and sprawl, to step and bound and trot in the semblance of a cat… (pg 31).”

They go to Angamandi and the court of Melko, where they come into contact with Karkaras (an early version of Carcharoth), who was suspicious of Lúthien, but her disguise on Beren held. Lúthien played her magic on the great wolf and put him to sleep “until he was fast in dreams of great chases in the woods of Hisilómë when he was but a whelp… (pg 31).”

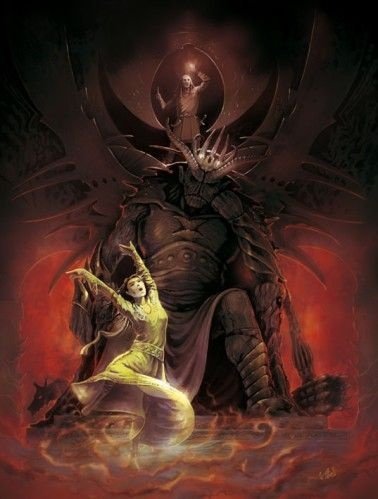

Both Lúthien and Beren make their way to Melko’s throne room, filled with cats and creatures, and Beren blended in with them, and took up a “sleeping” position underneath Melko’s throne. Lúthien on the other hand stood with pride before the Ainu, “Then did Tinúviel begin such a dance as neither she nor any other sprite or fay or elf danced ever before or has done since, and after a while even Melko’s gaze was held in wonder (pg 32).”

Everyone in the chamber, all the cats, thralls, Fay, and even Beren, fell asleep while listening to Tinúviel’s Nightingale voice. Her movements were just as hypnotizing, “and Ainu Melko for all his power and majesty succumbed to the magic of that Elf-maid, and indeed even the eyelids of Lórien had grown heavy had he been there to see (pg 33).”

Tinúviel woke Beren, careful to let everyone else continue to sleep. “Now does he draw that knife that he had from Tevildo’s kitchens and he seizes the mighty iron crown, but Tinúviel could not move it and scarcely might the thews of Beren avail to turn it (pg 33).”

They eventually pry one Silmaril off the crown, but Beren goes for a second one in his greed, only to break his blade and wake Melkor. Tinúviel and Beren fled Angamandi, pursued by Karkaras, the Great Wolf. They battled, and Karakaras bit off Beren’s hand bearing the Silmaril.

But, “being fashioned with spells of the Gods and Gnomes before evil came there; and it doth not tolerate the touch of evil flesh or of unholy hand (pg 34).” So Karkaras began to be burned alive from the inside out and screamed for all he had. The screams of the Great Wolf woke the castle, and Beren and Tinúviel fled for their lives.

They ran with an entire Orc army of Melko on their trail and had many encounters with them but eventually “stepped within the circle of Gwendeling’s magic that hid the paths from evil things and kept harm from the regions of the woodelves (pg 35).” Otherwise known as the Girdle of Melian.

They make their way to the king, and we get the quote that opens this essay, but Tinwelint saw no Silmaril, so they related the tale, and Beren stood before the king and said, “‘Nay, O King, I hold to my word and thine, and I will get thee that Silmaril or ever I dwell in peace in thy halls (pg 38).'”

So Beren went back out into the wilds to find the body of Karkaras and claim the Silmaril, but he didn’t go alone. “King Tinwelint himself led that chase, and Beren was beside him, and Mablung the heavy-handed, chief of the king’s thanes, leaped up and grasped a spear (pg 38).”

They eventually came upon a vast army of wolves, and among them was Karkaras, still alive but howling in agony. There was a great battle, “Then Beren thrust swiftly upward with a spear into his (Karkaras) throat, and Huan lept again and had him by a hind leg, and Karkaras fell as a stone, for at that same moment the king’s spear found his heart, and his evil spirit gushed forth and sped howling faintly as it fared over the dark hills to Mandos; but Beren lay under him crushed beneath his weight (pg 39).”

Beren was mortally wounded beneath Karkaras, and they tried to nurse him back to health. In the meantime, Tinwelint and Mablung found the Silmaril in Karkaras’ body. Tinwelint refused to take it unless Beren gave it to him to honor the fallen warrior, so Mablung grabbed the Silmaril and handed it to Beren, who, with his dying breath, said, “‘Behold, O King, I give thee the wondrous jewel thou didst desire, and it is but a little thing found by the wayside, for once methinks thou hadst one beyond thought more beautiful, and she is now mine (pg 40).'”

The tale ends with Beren dying, and we get a short interlude of Vëannë telling Eriol that there were many other tales of Beren coming back to life but that the only one she thought was true was the tale of the Nauglafring, otherwise known as the Necklace of the Dwarves.

The tale’s bones are the same all the way through, with some very significant character changes, like the addition of Celegorm and Curufin and the subtraction of Tevildo. Still, quite honestly, these things are entirely necessary because, on its own, this is just a tragic tale. When you add the other elements, the world expands, and the characters gain more agency. Suddenly, Beren’s quest affects far more than just the players in the story, and we get a much broader realization of what Beleriand is, was, and will become.

Join me next week for a short second edition of this tale, some commentary, and some final thoughts!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2; Beren and Lúthien

“One day he was driven by a great hunger to search amid a deserted camping of some Orcs for scraps of food, but some of these returned unawares and took him prisoner, and they tormented him but did not slay him, for thier captain seeing his strength, worn through he was with hardships, thought that Melko might perchance be pleasured if he was brought before him and might set him to some heavy thrall-work in his mines or in his smithies. So came it that Beren was dragged before Melko, and he bore a stout heart within him nonetheless, for it was belief among his father’s kindred that the power of Melko would not abide for ever, but the Valar would hearken at last to the tears of the Noldoli, and would arise and bind Melko and open Valinor once more to the weary Elves, and great joy should come back upon Earth (Pg 14-15).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we travail the beginning of the quest for a Silmaril and the humble beginnings of the story in The Book of Lost Tales.

We left off last week with Beren heading out to get the Silmaril from Melkor’s crown to curry favor of Tinwelint and acquire Tinúviel’s hand in marriage. Immediately Beren is in dangerous land:

“Many poisonous snakes were in those places and wolves roamed about, and more fearsome still were the wandering bands of the goblins and the Orcs – foul broodlings of Melko who fared abroad doing his evil work, snaring and capturing beasts, and Men, and Elves, and dragging them to their lord (pg 14).”

Beren was nearly captured by Orcs numerous times, battling all manner of creatures on his way to Angamandi (Melkor’s hold in the Iron Mountains). “Hunger and thirst too tortured him often, and often he would have turned back had not that been well neigh as perilous as going on (pg 14).”

These travels lead us right to the quote that opens this essay. Beren angered Melkor because he represented the kinship between Elves and Men “and said that evidently here was a plotter of deep treacheries against Melko’s lordship, and one worthy of the tortures of Balrogs (pg 15).”

Beren gave Melkor a speech that seemed inspired by the Valar and moved Melkor. Rather than killing him, Melkor decided that he should be sent to the kitchen and become a Thrall of Tevildo, Prince of Cats.

I want to step back here and review what changes Tolkien made to the tale over time.

The framework of the story is the same; however, In The Silmarillion, Beren left Neldoreth (The forests of Thingol and Melian) and made his way to Nargothrond to garner the help of Finrod Felagund, Elven King. He recalled Finrod’s vow to help Barahir’s (Beren’s father) kin, and Finrod agreed to help Beren in his quest for the Silmaril.

Finrod gathered a group and disguised them all as Orcs to get close to Angband, but Sauron, the future Dark Lord, became suspicious of the group and captured them. He sent them to a deep pit and sent werewolves to kill them, which Finrod killed with his bare hands. However, he was mortally wounded and thus ended one of the great Elven Kings of legend.

Tolkien’s process of bringing in Finrod fills out the whole Legendarium much more because The Book of Lost Tales is just that, tales; disparate and singular. These are a collection of stories rattling around in Tolkien’s head which built the history of a world, but he needed connective tissue (and a lot of editing) to bring everything together.

Finrod and Fëanor’s sons, Curufin and Celegorm, become the connective tissue, rather than Tevildo, the Lord of Cats, who doesn’t appear beyond The Book of Lost Tales.

So now that Beren is in captivity, Lúthien can feel that something has gone wrong, so she goes to her mother Gwendeling (Melian) and asks her to use her magic and see if Beren still lives:

“‘He lives indeed, but in an evil captivity, and hope is dead in his heart, for behold, he is but a slave in the power of Tevildo Prince of Cats (pg 17).'”

So she went to her Father, Tinwelint, who was angered that she would want to go after Beren. She also asked her brother Dairon, who scoffed at the idea of her heading off into the wilds, so he went to Tinwelint and tattled on his sister (Daeron in The Silmarillion was an unrequited lover instead of brother, and went to Thingol (Tinwelint) to stop her, and hopefully save her. Tinwelint, in his anger, put her as far away from danger as punishment as he could:

“Now Tinwelint let build high up in that strange tree, as high as men could fashion thier longest ladders to reach, a little house of wood, and it was above the first branches and was sweetly veiled in leaves (pg 18).”

Stuck in the tree, with servants bringing her food and water and then removing the ladders so she couldn’t follow, Tinúviel’s yearning for Beren grew. She stayed up there for a while until she got a vision from the Valar that Beren was still alive and held in captivity, a thrall to Tevildo tasked with hunting for the great cats. Horrified that he was there because of her, and more importantly, the love that kept growing because she could not stop thinking of him, she devised a plan.

“Now Tinúviel took the wine and water when she was alone, and singing a very magical song the while, she mingled them together, and as they lay in the bowl of gold she sang a song of growth, and as they lay in the bowl of silver she sang another song, and the names of all the tallest and longest things upon Earth were set in that song… and last and longest of all she spake of the hair of Uinen the lady of the sea that is spread through all the waters (pg 19-20).”

Remember that the whole point of writing these tales was to build a mythology for England. You can see from reading them that Tolkien was heavily influenced by other fairy tales he read, both in preparation and for study.

Tinúviel rubbed her head in the mixture, and her hair grew to great length, much like Rapunzel did to escape her tower.

Unlike Rapunzel, Tinúviel fashioned a rope out of her hair. She refused anyone from coming up to her little tree house until she finished. Then dressed in a black cloak, she escaped and headed north to go and rescue Beren.

This part of Lúthien’s story is the tale of Rapunzel, except that Tolkien flipped the script and created a strong woman to go and rescue her man.

Join me next week as we continue the story, find the differences with The Silmarillion, and generally have a great time!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, Final Thoughts

“Melko shalt see that no theme can be played save it come in the end of Ilúvatar’s self, nor can any alter the music in Ilúvatar’s despite. He that attempts this finds himself in the end but aiding me in devising a thing of still greater grandeur and more complex wonder:–for lo! through Melko have terror as fire, and sorrow like dark waters, wrath like thunder, and evil as far from the light as the depths of the uttermost of the dark places, come into the design that I laid before you. Through him has pain and misery been made in the clash of overwhelming musics; and with confusion of sound have cruelty, and ravening, and darkness, loathly mire and all putrescence of thought or thing, foul mists and violent flame, cold without mercy, been born, and Death without hope. Yet is this through him and not by him; and he shall see, and ye all likewise, and even shall those beings, who must now dwell among his evil and endure through Melko misery and sorrow, terror and wickedness, declare in the end that it redoundeth only to my great glory, and doth but make the theme more worth the hearing, life more worth the living, and the World so much the more wonderful and marvellous, that of all the deeds of Ilúvatar it shall be called his mightiest and his loveliest.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we recap The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, and in doing so, speak about the more fantastic aspect of Middle-earth and Tolkien’s intention.

The Book of Lost Tales is an amalgam of Tolkien’s work throughout his life. Christopher has included some of his father’s earliest poems, scraps of notes stuck into notebooks, various illustrations, and books and books of re-writes to show the thought and care Tolkien put into the work.

John wanted to tell a fantastic story that would give people meaning. He wanted a new fairy tale that would anchor into our world and give people wonder and hope (and perhaps even give reasoning for things like The Great War).

Many critics have said that The Lord of the Rings is an allegory to Tolkien’s time in the war, and if you only read the book itself, it is easy to understand why. Tolkien, however, hated allegory and had often stated that he pulled inspiration from his time in the war, but there was no allegory there. That can be hard to swallow, especially when his fellow Inkling (a society of writers who met to critique and edit each other’s work), C.S. Lewis, thought allegory one of the greatest literary techniques.

The story produced in The Lord of the Rings was a work of love developed over many decades, but to create a work so deep and well established Tolkien wanted a robust history of the world, that history is what eventually became The Silmarillion.

But Tolkien, like many authors, wanted the history of the world to be a story in and of itself, so in the earlier iterations, we get the tale of Eriol, who in turn is told the story behind The Silmarillion.

The problem Tolkien ran into, however, was that history is difficult to tell in a story format. There are fantasies, records, and fairy tales told in the Silmarillion, but they come late in the book and feel more like what he would eventually write in The Lord of the Rings. The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, is Eriol learning instead about the Valar and how the Eldar (Gnomes in this earlier version) came into being. However, even in these earlier versions, we still need to catch minor differences with how Tolkien later decided to frame everything.

Facts, like the Maiar being the children of the Valar, the Eldar being Gnomes, and the sparse inclusion of Fëanor are stark differences to how the story eventually played out, and what is great about reading through this book was being able to read Christopher’s analysis (Tolkien’s son and editor) of where Tolkien tried to take the story, and where he decided to end up. This process is the magic of reading The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Part 2, I’m sure, will have just as many quirks, but part 2 is where the stories that built the history of Mankind came into being. Stories like the Lays of Lúthien, the Tale of Túrin Turambar, and the Fall of Gondolin all take place in the second half of these histories. These tales inform our characters in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Beyond The Silmarillion, there is minimal mention of the Valar or Ilúvatar.

In Christopher’s sentiment, the first book is less interesting because it’s about the development of the world itself and not necessarily about the people; thus, it’s harder to give stakes because we know what will eventually happen.

Knowing all this, Ilúvatar is the most provocative being or concept in Tolkien’s oeuvre. Ilúvatar is God for this World (even though the Valar intermittently are called gods, Tolkien later stripped them of that title for The Silmarillion).

The quote to start this essay is a perfect example of the fallibility of gods in general. Tolkien was deeply religious, and I’m sure he wrote Ilúvatar to be Middle-earth’s Yahweh and much of the struggle and philosophy in Middle-earth is how to accept or deal with the concept of Death. Death is a “gift” given to Man when they are born, so they might make life more meaningful. Death was not a concept until Morgoth sang its theme into existence.

This path makes Melkor the most tragic character in the pre-history of Middle-earth because, as we see from the opening quote, he has no choice. Ilúvatar, as the master creator, knew every theme he wanted to put into the world, and Death, hate, and suffering would be part of existence.

Iluvatar created each Vala to inform specific parts of his themes, but themes were all they were, meaning that the Valar had free will over what theme they were given. Iluvatar created Melkor to suffer. He created him to be a Dark Lord because he knew that without a Dark Lord making people work for their freedom, they would take their lives for granted.

Tolkien didn’t write Allegory; he wrote philosophy. Death is a gift because we cannot appreciate light without darkness. We cannot fully appreciate life without death.

Come join me next week as we begin our foray into “The Book of Lost Tales, part 2,” the second book of the Histories of Middle-earth!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Two Towers, Re-read

“‘All right!’ he said, ‘Say no more! You have taken no harm, There is no lie in your eyes, as I had feared. But he did not speak long with you. A fool, but an honest fool, you remain, Peregrin Took. Wiser ones might have done worse in such a pass. But mark this! You have been saved, and all your friends too, mainly by good fortune, as it is called. You cannot count on it a second time. If he had questioned you, then and there, almost certainly you would have told all that you know, to the ruin of us all. But he was too eager. But come! I forgive you. Be comforted! Things have not turned out as evilly as they might.'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we’re back with a bit of a lie, this isn’t quite a Blind Read, but it’s been so long since I’ve read these books it might as well have been!

Before we discuss the books, I want to start by saying how amazed I am at how close the Movies were to the books. After reading them more critically, it is obvious how much the producers revered the core material. The ability to create a new medium that was inclusive of all who did not read the books but to be honest enough to the core material that hardcore fans love is a masterstroke in adaptation.

The only significant difference the movies had was in Fellowship because they took out the entire Tom Bombadil sequence (rightly so). Still, even then, I’ve seen deleted scenes where the hobbits get swallowed up by Old Willow. We’ll cover the differences in The Two Towers below, but we also dive more into the world’s lore.

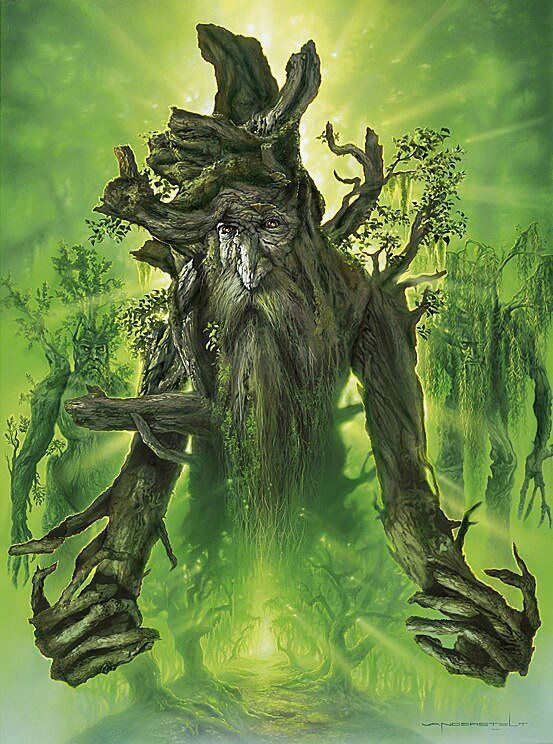

The first thing I’d like to mention is Treebeard and the Ents. The movie played up his slowness and mistrust, and where many lines are taken directly from the text, Treebeard was not very slow to action speaking of page count. Yes, he does suspect Merry and Pippin of being Orcs at first, but he quickly decides they aren’t. He then calls the council of Ents, and within a few pages, they choose to mount an attack on Orthanc. Again, the movie drew it out for drama, but the book had these events happening quickly.

However, the biggest oddity I noticed in the book was a seeming discrepancy between The Silmarillion and The Two Towers. When speaking of his race, Treebeard (also known as Fangorn) says the Elves created Ents. However, later in the book Gandalf (also known as Mithrandir, but more on that later) tells the remaining Fellowship that Fangorn is the oldest living creature on Middle-earth (remember that Elves, Vala, Maiar, and even Dwarves were created on Valinor). Tom Bombadil verifies this statement in The Fellowship of the Ring. I stopped and thought about this before I could move on because I know that Tolkien re-wrote much of the history and was still in his re-writes while writing The Lord of the Rings, but was there a discrepancy this bold?

I decided to go back and do some digging to figure it out.

Returning to The Silmarillion, I verified that Yavanna (the Vala who was the “lover of all things that grew in the earth”) created Ents as part of her music theme. Part of her reason for doing so was because of other creations, such as the Dwarves (who were created but kept at rest for many years). Yavanna feared the trees themselves would not have a means of protecting themselves against the push of other creatures’ industrial nature (something that echoes Tolkien himself), so she made the Ents to be shepherds and protectors of the trees and forests. Tolkien even had an early iteration where he called them Tree Ents because the word Ent was derived from the Old English word Eoten, meaning Giant, so they were Tree Giants meant to protect. Tolkien seeds this in The Fellowship of the Ring when Samwise relays a story from his cousin Hal, who saw a “treelike giant” north of the shire. This anecdote was Tolkien’s way of seeding their entrance into the books.

So we know that Yavanna created the Ents – why then does Treebeard say that they were a creation of the Elves? Looking back at the text, one can see where I went wrong. The Ents and Entwives were creatures of the earth, and where they were sentient, they couldn’t communicate with other animals. They were meant solely to be of and for nature, so Treebeard says that the Elves taught them to speak Elvish and opened their minds to interact with other sentient creatures. The Elves brought the Ents to life; they didn’t create them.

I could go on and on about Ents and make it their own essay, but since this is about a re-read of The Two Towers, I want to dig into a few other short items.

The first is Gandalf. In The Fellowship of the Ring, he is of the gray order of the Istari (Maiar wizards), but because of his fall against the Balrog in that first book, he came back as an Istari of the White order, which is one of the most powerful, second only to the Black Order. This book teaches that the Istari are immortal like their masters, the Valar. Gandalf returned as a white-order Istari because of the power vacuum of Saruman, who abandoned his order for power. Saurman did not specifically side with Sauron (which we learn in The Silmarillion). Still, the Palantir corrupted him enough that he thought he could become the most powerful being in Middle-earth.

It isn’t until Gandalf returns that the party nearly ceases calling him by his common “gray” name, Gandalf. Instead, once he takes up the white mantle, most characters call him Mithrandir for the remainder of the series.

Lastly, I would be remiss if I didn’t bring up what confused me the most when I read through the books before reading The Silmarillion—the Dúnedain and Aragorn’s lineage.

Throughout this book, there are constant references to Elendil and Eärendil, but I didn’t know who those people were other than they were Aragorn’s ancestors. Having that foreknowledge made the events and exposition of the story that much more lush and meaningful. It adds weight to Aragorn’s decisions and makes him a more dynamic character. Upon the first read, much of his character felt very one note and much more severe than was necessary. Still, after getting the history behind his lineage, one can genuinely feel the dynamics at play and the choices he must make as he forges his way to coming back to be King of the world of Men.

Come back next week as we continue “The Music of the Ainur” in the Book of Lost Tales!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1, The Music of the Ainur part 2

“Through him has pain and misery been made in the clash of overwhelming musics; and with confusion of sound and have cruelty, and ravening, and darkness, loathly mire and all putrescence of thought or thing, foul mists and violent flame, cold without mercy, been born, and death without hope. Yet is this through him and not by him; and he shall see, and ye all likewise, and even shall those beings, who must now dwell among his evil and endure through Melko misery and sorry, terror and wickedness, declare in the end that it redoundeth only to my great glory, and doth but make the theme more worth the hearing, Life more worth the living, and the World so much the more wonderful and marvellous, that of all the deeds of Ilùvatar it shall be called his mightiest and his loveliest (pg 55).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we delve into the philosophy of Tolkien as we review “The Music of the Ainur,” the second chapter of The Book of Lost Tales.

Tolkien himself was a deeply religious and highly intellectual man. He surrounded himself with others of all opinions (see his writing group The Inklings, which included C.S. Lewis), and at the forefront of his mind was an anthropologic focus on the world. This curiosity of how the world works is what created the fantasy world we all respect so much.

This chapter, in particular, is about how Ilùvatar (God in this iteration) created the world through his Angels, which he named Valar.

Rúmil tells the story to Eriol and begins his tale by saying, “Before all things he sang into being the Ainur first, the greatest is thier power and glory of all his creatures within the world and without (pg 52).”

This passage marks Ilúvatar as a great creator. There is nothing closer to authentic Christianity than this first chapter, as it shows Ilúvatar’s great power and ability of forethought and humility.

Rúmil goes on, “Upon a time Ilúvatar propounded a mighty design of his heart to the Ainur, unfolding a history whose vastness and majesty had never been equalled by aught that he had related before, and the glory of it’s beginning and the splendour of its end amazed the Ainur, so that they bowed before Ilúvatar and were speechless (pg 53).”

Thus enters the theme of Predestination. Ilúvatar creates a concept that has a beginning and an end. But for such a grand creator, that is not satisfactory because there is no surprise in the world, no joy in watching the events of his grand scheme unfold. To counter this problem, Ilúvatar tells his Angels (they are interchangeably called Ainur and Valar), “It is my desire now that ye make a great and glorious music and a signing of this theme; and (seeing that I have taught you much and set brightly the Secret Fire within you) that ye exercise your minds and powers in adorning the theme to your own thoughts and devising (pg 53).”

Ilúvatar allows the Vala to create the middle of his great tale with their own “secret fire.” We learned in The Silmarillion (and to a lesser extent here) that the Vala all have their own minds, and they all have their passions. This is what the secret fire is, a passion for seeing something created, which is mirrored in Tolkien himself as he created the world of Middle-earth. That is not to say that Tolkien thought himself a god, or even to the level of the Valar, but he saw it as his duty to show that there was great beauty in the world. He wanted to elicit this emotion from people because of his experiences in the Great War. Let me explain:

“Yet sat Ilúvatar and hearkened till the music reached a depth of gloom and ugliness unimaginable; then did he smile sadly and raised his left hand, and immediatly, thoguh none clearly knew how, a new theme began among the clash, like and yet unlike the first, and it gathered power and sweetness (pg 54).”

This passage shows both the power and the weakness of the Valar, which in turn displays just how human they were. Which makes sense because we, as people, are the antecedents of the Angels. Humans are called Ilúvatar’s second children (after the Elves). The Valar wanted to create something with the same power as Ilúvatar, but they became despondent when things turned dark, and their grand theme became black with peril.

Indeed it was Melkor, later called the Dark Lord and master of Sauron, who saw this darkness and believed it was the only way to the end of the story.

“Mighty are the Ainur, and glorious, and among them is Melko the most powerful in knowledge (pg 54).”

Tolkien believed there was a balance to the world, making Predestination possible. Each Valar had their power or strength; Ulmo had control over water, Manwë had power over the air (The great eagles which bore Gandalf away from Orthanc and Frodo and Sam away from Mount Doom were agents of Manwë), and Aulë had control of the earth. But it was Melkor who had the greatest knowledge, and what Tolkien learned in World War I was that one could have a perception of darkness or a general concept of pain, but until you have the experience, you never really have knowledge of it.

Knowledge equals pain, which is a prime theme in Tolkien’s work. That may seem particularly depressing, but you cannot appreciate the most glorious mornings until you see the darkest of nights (this echoes in Sam’s speech at the end of The Two Towers. “They were holding on to something…”). Ilúvatar created Melkor to have the knowledge and sing about that knowledge which fostered despair in the world, but he could do nothing to change it. He became the Dark Lord because once the Children of Ilúvatar were created, they received gifts to experience the world’s joys and perils, whereas Melkor could only see troubles and darkness.

The Eldar were given long life and foresight that they would live to see the end of all time, which made them happier than humans. But to humans, Ilúvatar gave the gift of death.

Doesn’t it seem like much of a gift? Well, it harkens back to the question of knowledge. If you knew your time was short, you would live a more extraordinary life, a life filled with great pain and great joy, rather than being stuck in the middle and being “emotionless” as the Elves were.

This ability to have great highs and lows was specifically why Ilúvatar sang Melkor (also known as Morgoth) into existence. He knew what the Valar would do, but also knew it was necessary for a full experience of the world.

Come back next week for a recap and reread of “The Two Towers!”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1, Chapter 2: The Music of the Ainur

“Then slept Eriol, and through his dreams there came a music thinner and more pure than any he heard before, and it was full of longing. Indeed it was as if pipes of silver or flutes of shape most slender-delicate uttered crystal notes and threadlike harmonies beneath the upon upon the lawns; and Eriol longed in his sleep for he knew not what (pg 46).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we head back to The Book of Lost Tales and tackle Chapter Two’s opening, “The Music of the Ainur.” Christopher added something new to this chapter from the notes of this father and the result sheds light on the meaning of the chapter. When he began writing Eriol’s story, Tolkien created a transitional piece between the beginning of the story of the Ainur and The Cottage of Lost Play. We’ll be covering that transitional piece this week because there is so much in it that warrants discussion before we move on!

Before we get too far into it, I want to delve a little deeper into the difference between Gnomes and Elves, which has been a strange adjustment because I wasn’t sure if Tolkien was calling all Elves (otherwise known as Eldar) Gnomes or if it was only Noldor (also known as Noldori) Elves. Part of the confusion comes in because of all the different names involved.

Tolkien wanted the world to be lush and complete, but because of who he was and his background, Worldbuilding to Tolkien didn’t mean delving into culture, landscape, or image. Instead, to Tolkien, what made people unique was how they communicated, meaning language. Thus, the language and the beings who utilized this language changed through his world’s creation.

For example, the Teleri later become the Vanyar, The Noldoli (Gnomes) later become the Noldor, and the Solosimpi later become the Teleri. Why did he make all of these changes? Because of language.

The perfect example of this is what we began with: Gnomes. The word Gnomes brings to mind that small bearded garden variety with red pointy hats. I’m sure at some point in the writing of this epic; an editor approached Tolkien who mentioned that that word did not elicit that “They were a race high and beautiful… They were tall, fair of skin and grey-eyed, though their locks were dark, save in the golden house of Finrod (pg 44).” (just to be clear we are explicitly talking about the Gnomes or Noldor Elves. Christopher goes out of his way to make sure that is clear: “Thus these words describing characters of face and hair were written of the Noldor only, and not of all the Eldar… (Pg 44)“

So why did Tolkien call them Gnomes? Yep, you guessed it. Language! “I have sometimes used ‘Gnomes’ for Noldor and ‘Gnomish’ for Noldorin. This I did, for whatever Paracelsus may have thought (if indeed he invented the name) to some ‘Gnome’ will still suggest knowledge.”

In Greek, gnome meant thought or intelligence. Which then translated into words such as gnomic or gnostic. When Tolkien mentions Paracelsus, he refers to the 16th-century writer who used gnome as a synonym for pygmaeus, which means “earth-dweller.”

Tolkien was trying to establish that the Noldor were intelligent creatures who understood how the world worked. But he was also trying to create a distinction between the Noldor and the Valar. The two types of beings were almost interchangeable because they were both created by Ilúvatar.

At the beginning of this interlude, Eriol asks for clarification (Tolkien’s way of trying to clarify it himself): “Still there are many things that remain dark to me. Indeed I would fain to know who be these Valar; are they the Gods?” to which Lindo responds “So they be (pg 45).” And yet later, when describing gnomes, “nor might one say if he were fifty of ten thousand (pg 46).”

So he creates differences through the use of language. Both from the meaning of their names and the languages they speak. These themes also carry over into The Lord of the Rings because everyone has their distinct dialect, from Rohan to Gondor, from The High Elves of Rivendell to the woodland elves in Lothlórien. Here on Tol Eressëa, “there is that tongue to which the Noldoli cling yet – and aforetime the Teleri, the Solosimpi, and the Inwir had all their differences (pg 48).”

Language was a big theme in this introduction to make sure the reader understands what they are getting themselves into, but there are two other themes Tolkien stamps down, which carry over into all of his other writing; dreams and music.

All of these things are interconnected, and I chose the quote to open up this essay because it holds the essential themes Tolkien has brought into this tale.

If we remember from the first chapter (or go back and read it here), Eriol is a human of modern times. He travels and finds his way to Tol Eressëa, and he is a means to an end to tell the story of the beginning of time and the first age. What I find particularly interesting is that Tolkien intended there to be a “dream bridge” between Tol Eressëa and the rest of the world. So that outsiders could not find it while awake, and their knowledge of the isle would fade upon waking as dreams do; but dreams also leave us with subconscious memory, and feeling that stick with us, though we don’t remember details.

This intermittent chapter begins with Eriol heading to a room and falling asleep, and in that sleep, “came a music thinner and more pure than any he had heard before (pg 46).”

The Music of the Ainur, which we will get more into next week, is how the Valar (also known as Ainur) created the world. Their music brought into being plants, animals, and earth, as well as emotion and consciousness. This “pure music” is what Eriol hears in his mind as he sleeps. It is not the sound as it was when it created the world, but Tol Eressëa is so close to the center of everything that it echoes what came before. He hears the music of creation, and he doesn’t consciously recognize it, but he subconsciously melds into it.

I also find it interesting that he falls asleep and delves into dreams directly before being told the tale. Could it be that the entirety of The Book of Lost Tales is told through the Music of the Ainur while Eriol is sleeping?

Let’s see if we find out next week as we begin the Music of the Ainur!

You must be logged in to post a comment.