Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of Beleriand and its Realms, pt. 1

“Thus the realm of Finrod was the greatest by far, though he was the youngest of the great lords of the Noldor, Fingolfin, Fingon, and Maedhros, and Finrod Felagund. But Fingolfin was held overlord of all the Noldor, and Fingon after him, though their own realm was but the northern land of Hithlum; yet their people were the most hardy and valiant, most feared be the Orcs and most hated by Morgoth.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we delve into the realm of Beleriand and gain a greater understanding of where each faction of the Eldar takes as their home.

The book has gone beyond being very dry to transitioning to some fascinating tales. So, unfortunately, this chapter takes a step backward, but for an important reason:

“This is the fashion of the lands into which the Noldor came, in the north of the western regions of Middle-earth, in the ancient days; and here also is told of the manner in which the chieftains of the Eldar held their lands and the leaguer upon Morgoth after the Dagor Aglared, the third battle in the Wars of Beleriand.”

We finally get some reference to the locations and people described.

Tolkien was known to love nature and hate what industry did to the purity of the world. We can see this in The Lord of the Rings movies on full display with the destruction of Fangorn Forest through the industry of Isengard. Here, in the First Age, Morgoth does much the same. First, he makes his fortress in the wastes of the north and calls it Angband, otherwise known as “The Hells of Iron.” He then built a great tunnel leading out of Ered Elgin (Ered is the Elvish name for Mountain. Thus, Ered Elgin is called the Iron Mountains) for his minions to spread throughout Beleriand. At the end of this tunnel, he built a mighty gate, “But above this gate, and behind it even to the mountains, he piled the thunderous towers of Thangorodrim, that were made of the ash and slag of his subterranean furnaces, and the vast refuse of his tunnelings.”

This passage shows the Evil (with a capital E) in Tolkien’s eyes. The destruction of the world in the (false) name of progress.

But since this chapter glosses over events, for want of explaining locals, we switch to the other residents of Beleriand who managed to live with and in the world, just as Yavanna’s song of creation would have them.

“To the West of Thangorodrim lay Hísilómë, the Land of Mist…Hithlum it became in the tongue of the Sindar who dwelt in those regions.“

From my meager knowledge, I believe that the lands of Beleriand make up much of what we know of the landscape of Middle-earth in the Third Age, and based upon the name of the region, could this be what will become the Misty Mountains? There is no direct correlation except through the wording. However, Tolkien was always so specific with his world and language that I will go out on a limb and say it’s so.

Then we come across another little gem hidden in the text. Within Hithlum to the south is a region known as Dor-Lómin:

“But their cheif fortress was at Eithel Sirion in the east of Ered Wethrin, whence they kept watch upon Ard-galen; and their cavalry rode upon that plain even to the shadow of Thangorodrim, for from few their horses had increased swiftly…Of those horses many of the sires came from Valinor,”

I have to wonder if these are the glorious beginnings of the wonderous horses of the Rohirrim, which we see in “The Two Towers” as the riders of Rohan, whose duty it was to guard the fields of that land. Again there is no definitive statement, but it makes quite a bit of sense.

Moving west still, we go to Nevrast, where “for many years was the realm of Turgon the wise, son of Fingolfin.” Nevrast was a marshy land settled between the sea and the mountains where most of the Grey-elves lived.

Directly east of Dor-Lómin, across Ered Wethrin and Tol (Elvish for River) Sirion, lay Dorthonion where “Angrond and Agnor, sons of Finarfin, looked out over the fields of Ard-galen.” and in the west of Dorthonion was the Tol Sirion, where Finrod ruled. It was there, “in the midst of the river he built a mighty watch-tower, Minas Tirith; but after Nargothrond was made he committed that fortress mostly to the keeping of Orodreth, his brother.“

Minas Tirith! I had no idea Minas Tirith was built in the first age! No wonder it is so massive and beautiful! It was created in the “Pass of Sirion,” the largest and most prominent passage to Beleriand from Ard-galen and where Morgoth would most likely take a straight shot to attack that land. Minas Tirith, and Gondolin, which were built on the opposite side of the river, are the two most significant guardians of the land created by the Eldar.

The last region we’ll talk about this week is the March of Maedhros, which was east of Dorthonian. It was here “dwelt the sons of Fëanor with many people, and their riders often passed over the vast northern plain, Lothlann the wide and empty, east of Ard-galen, lest Morgoth should attempt any sortie against East Beleriand.”

This region was known as Himring, the Ever-cold, “and that was wide-shouldered, bare of trees, and flat upon its summit, surrounded by many lesser hills.” I thought about this area quite a bit, and I wonder if this might be Weathertop, where Frodo took the poison of the blade of the nine. The description of the geography seems appropriate, but I’m unsure of the region.

What is so fascinating is that the Gray Elves, or Sindar, had never gone to Valinor. Instead, Thingol married a Maiar named Melian, and they took up residence in Beleriand (look back at the Girdle of Melian here). Still, it was Fëanor and Fingolfin who came after during the departure of the Noldor from Valinor. These two relations took a protective stance against the rest of the realm.

All locations described in this part of the chapter are lookouts or guards surrounding Ard-Galen so that they might protect against Morgoth and his minions. The opening quote of this essay describes their purpose nicely because it’s curious that Thingol, the Elf who had been there the longest, with a Wife who is more powerful than any Eldar, would hide within their girdle. At the same time, the Noldor would be the protectors. But it is because of that hatred Fëanor had for Morgoth that this came to being.

When he died, his sons took up his mantle, and where they didn’t have the fire, he had to go after Morgoth actively; they took it as their duty to guard the land and stop The fallen Valar from further destruction.

Join me next week as we cover the remainder of Beleriand and complete this chapter!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of the Return of the Noldor, Conclusion

“In many parts of the land the Noldor and the Sindar became welded into one people, and spoke the same tongue; though this difference remained between them, that the Noldor had the greater power of mind and body, and were mightier warriors and sages, and they built with stone, and loved the hill-slopes and open lands.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we conclude “Of the Return of the Noldor.” and have a deeper discussion about how the world progresses.

We completed the last chapter with Fëanor dying, Maedhros (Fëanor’s son) kidnapped by Morgoth, and Fingon, son of the rival clan of Fingolfin, saving him.

This second portion of the chapter is about the Eldar taking a stake in the land. In contrast, the first half of the chapter was about the fury of Fëanor and the repercussions of that drive to destroy Morgoth (which ultimately failed. Morgoth is still in power at Angband in the north, and he still has the Silmarils). Finally, after “twenty years of the Sun had passed,” this chapter takes place when Fingolfin held a great feast known as the “Feast of Reuniting.”

This gathering brought together Eldar of all kinds together in the woods of Beleriand. They began to learn each other’s languages and healing began to happen, but still, Morgoth brooded in the north.

Tolkien then takes us another thirty years further into the future, past the time of ease and Elves coming together. During this time, Finrod took precedence ahead of all other Elves. Ulmo, the Valar of the Seas, gives both Finrod and Fingolfin a vision that shows trouble caused by Morgoth streaming out from Angband. Both relatives internalize this message and design not to address it with each other, thus preparing for the coming war separately instead of on a conjoined front.

Finrod then brings his sister Galadriel to Doriath, the region which houses Menegroth, the underground mansion of Thingol. “Then Finrod was filled with wonder at the strength and majesty of Menegroth, its treasures and armouries and its many-pillared halls of stone; and it came into his heart that he would build wide halls behind ever-guarded gates in some deep and secret place in the hills.” This “secret place in the hills” soon became known as Nargothrond, which was based on Menegroth and aided in construction by the Dwarves of the Blue Mountains. This secret mansion was the beginning of Finrod’s plans to protect his people against the might of Morgoth when he decided to attack.

But what of Galadriel? She “went with him not to Nargothrand, for in Doriath dwelt Celeborn, kinsman of Thingol, and there was great love between them. Therefore she remained in the Hidden Kingdom, and abode with Melian, and of her learned great lore and wisdom concerning Middle-earth.“

Celeborn is still with her in the Third Age when the Fellowship goes to greet them. He is King to her Queen and stands beside her when they meet the nine wanderers. Here, she came to great power because she learned from Melian, a Maiar, second in power only to the Valar themselves (Gandalf himself is Maiar), which is why I believe she knows so much is so powerful by the time the Third Age comes around.

Concurrently, while Finrod is building his home, while Thingol is hiding in his girdle, while Fingolfin is making his lands in Mithrim, Morgoth stirred. “Believing the report of his spies that the lords of the Noldor were wandering abroad with little thought of war,” he decided to make his move. So his army of Orcs poured south through the fields of Ard-galen, “But Fingolfin and Maedhros were not sleeping,” and they led a host of warriors and utterly wiped out Morgoth’s brood.

“That was the third great battle of the Wars of Beleriand, and it was named Dagor Aglareb, the Glorious Battle.”

The Noldor pushed Morgoth back to Angband and laid siege to the fortress, “Yet the Noldor could not capture Angband, nor could they regain the Silmarils; and war never wholly ceased in all that time of the Siege, for Morgoth devised new evils, and ever and anon he would make trial of his enemies.”

Through hundreds of years following this, there were many skirmishes where Orcs would make their way out of Angband but got consistently pushed back. Even Morgoth’s “new evils” such as “Glaurung, the first of the Urulóki, the Fire Drakes,” could not forge a wedge into the foothold the Noldor had in Beleriand. In fact, after Glaurung’s defeat and retreat to Angband, “…there was the Long Peace of well-nigh two hundred years” where the Noldor and the Sindar built lives and homes in Beleriand.

We are beginning to see how its residents separate Beleriand. The Dwarves are in the Mountains of the East, concerned only with mining and producing their minerals. Many mention their isolationist stance. They don’t care what’s going on above ground in Beleriand and only work with the Noldor and Sindar because they trade.

The Sindar take up residence right smack dab in the middle of the land. Still, the Noldor take the western coast and the northwest with Mithrim (which I also find interesting because of the notorious mineral the Dwarves make into some of the most fantastic armor in the world – Mithril is very close in name to this Noldor held land).

Then there is Morgoth, who is held in his citadel in Angband in the north, too far north, in fact, for any map I’ve seen to show where Angband is.

So what happens next? Do we get any more information about the land and its peoples? Next week, let us find out in “Of Beleriand and it’s Realms.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of the Return of the Noldor pt. 1

“The hearts of the Noldor were high and full of hope, and to many among them it seemed that the words of Fëanor had been justified, bidding them seek freedom and fair kingdoms in Middle-earth; and indeed there followed after long years of peace, while their swords fenced Beleriand from the ruin of Morgoth, and his power was shut behind his gates. In those days there was joy beneath the new Sun and Moon, and all the land was glad; but still the Shadow brooded in the north.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we delve into the lore of the Noldor Elves and begin to see that despite the chapter name’s promise, Valinor is now beyond the reach of our supposed protagonists.

I began this chapter assuming that the title “Of the Return of the Noldor” would have to do with them returning to Valinor; however, as the chapter progressed, I realized that the name intended to show that the name’s meaning was the Noldor had returned to Beleriand to stay.

This chapter shows many great struggles over the land of Beleriand between the Eldar (the elves) and Morgoth, including two different “wars for Beleriand.“

We begin by rehashing previous chapters, the landing of Fëanor and his sons “on the outer shores of the Firth of Dengrist.” They “made their encampment” in Mithrim, in the northwest of Beleriand. Morgoth, seeing the flames of the ships they burned to stop Fingolfin from following them, anticipated their arrival and brought a host of foes to attack them. The skirmish is “the Second battle in the Wars of Beleriand,” and in Elvish, Dagor-nuin-Giliath, or “The Battle Under the Stars.”

We have jumped around in time in telling these histories because this battle took place before the creation of the Sun and Moon that we saw a few chapters ago. The altercation is known as “The Battle Under the Stars” because neither the Sun nor Moon had risen. Any light in Beleriand came from the stars of Valinor.

But Morgoth made an error in judgment because he didn’t truly comprehend the fury of Fëanor and his vast hatred for Morgoth:

“The Noldor, outnumbered and taken unawares, were yet swiftly victorious, for the light of Aman was not yet dimmed in their eyes.”

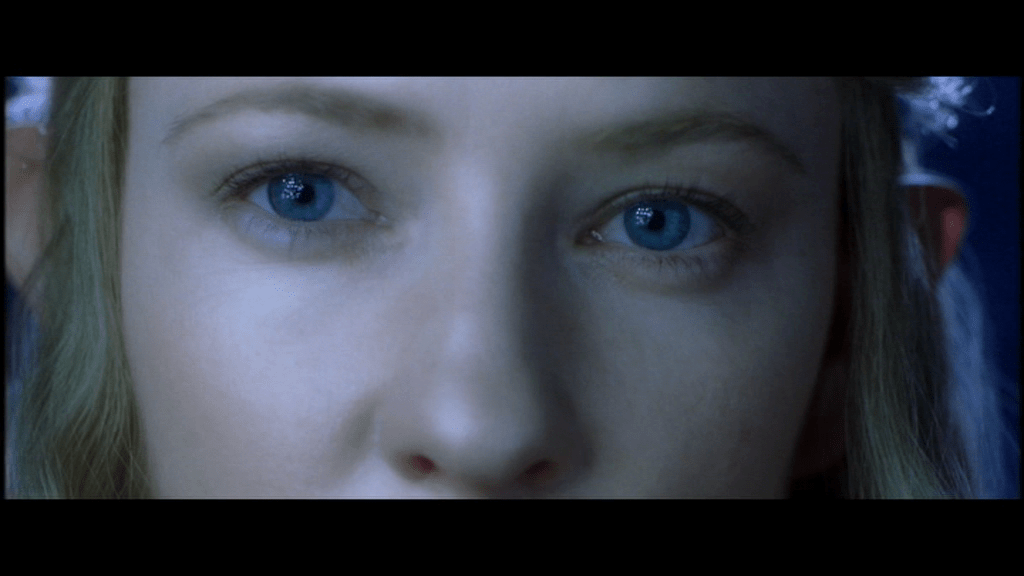

The starlight is the same light you see in Galadriel’s eyes in the movie, as she is the last of the Noldor who had lived to see the stars of Valinor.

Fëanor pushed Morgoth’s forces back to Ard-galen (above the mountains at the very north of Beleriand) and his stronghold at Angband. The Noldor had won, but Morgoth struck a victory because “Fëanor, in his wrath against the Enemy, would not halt, but pressed on behind the remnant of the Orcs, thinking so to come at Morgoth himself.“

Fëanor became surrounded by Balrogs, and “at the last he was smitten to the ground by Gothmog, Lord of the Balrogs.“

Fëanor’s sons rescued him from Gothmog and the Balrogs, but the blow was fatal and knew, just before “his body fell to ash, and was borne away like smoke” that “no power of the Noldor would ever overthrow” Angband.

Maedhros, Fëanor’s eldest son, took control of the Noldor and accepted terms from Morgoth, “acknowledgeing defeat, and offering terms, even the surrender of a Silmaril.” Still, it was a trap, and Maedhros was captured, his host slaughtered.

Maedhros’ brother’s retreated to regroup, and at this time, Fingolfin made his way across the icy torrential pass between Valinor and Beleriand. At this time, the Sun rose in the sky, and the dark loving host of Morgoth retreated to the darkness of Angband and its surrounding mountains.

Fingon, the son of Fingolfin, saw more similarities between the Eldar than differences and made a daring plan to save Maedhros and try to bring the Elves together. First, he went to Angband. “Then in defiance of the Orcs, who cowered still in the dark vaults beneath the earth, he took his harp and sang a song of Valinor that the Noldor made of old, before strife was born among the sons of Finwë; and his voice rang in the mournful hollows that had never heard before aught save cries of fear and woe.“

Maedhros hears this song and cries out for him to end him and his torment, but Manwë (the Valar) also hears this song of hope and sends help. “There flew down from the high airs Thorondor, King of Eagles, mightiest of all birds that have ever been, whose outstretched wings spanned thirty fathoms; and stayed Fingon’s hand he took him up, and bore him to the face of the rock where Maedhros hung.“

Strife and distrust continued for many years, but there was gradual acceptance between the different tribes of Elves in Beleriand. The Dwarves, also distrusting, agreed to assist in light of the terror of Morgoth’s influence over the land.

The one hold out was King Thingol, who was safely interred in his “girdle of enchantment.” However, Thingol gave leave for the Noldor and the Naugrim (Dwarves) to stay in the surrounding lands:

“In Hithlum the Noldor have leave to dwell, and in the highlands of Dorthonion, and in the lands east of Doriath that are empty and wild; but elsewhere there are many of my people, and I would not have them restrained of their freedom, still less ousted from thier homes.“

I get the feeling that Thingol will play a much more significant role in things to come, but thus far, he has decided to hole up and take an isolationist stance against Morgoth. We see this echoed in The Lord of the Rings, as initially, the elves want nothing to do with the war against Sauron. Will Thingol change his mind?

Next week, let’s find out as we cover the second half of the chapter “Of the Return of the Noldor.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of Men

“To Hildórien there came no Vala to guide Men, or to summon them to dwell in Valinor; and Men have feared the Valar, rather than loved them, and have not understood the purposes of the Powers, being at variance with them, and at strife with the world.“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we learn of a new species born into Beleriand, Men, and how they came to inherit the world.

This chapter is unique because it gives us a basic overview of how Men (Tolkien uses Men as a stand-in to mean Human-kind) came into being, but Tolkien does not expound upon the History of Middle-earth. Instead, this feels more like his effort to understand the motivations (and potential weaknesses) of Men as unknowing Children of Ilùvatar.

Tolkien tells us: “At the first rising of the Sun the Younger Children of Ilùvatar awoke in the land of Hildóren in the eastward regions of Middle-earth; but the first Sun arose in the West, and the opening eyes of Men were turned towards it, and their feet as they wandered over the Earth for the most part strayed that way.”

Men were called Hildor, otherwise known as the followers, not because they were sheep, but because they were born after Elves and Dwarves. They also had many other names, “the Usurpers, the Strangers, and the Inscrutable, the Self-cursed, the Heavy-handed, the Night-fearers, the Children of the Sun.“

Men were born after the glory of Valinor, and they knew only the cold, complex beauty of Beleriand. They awoke without the knowledge of the Valar or Ilùvatar, which was the Quendi birthright. They were born without knowledge of the light of the Trees of Valinor. All they had was the Sun.

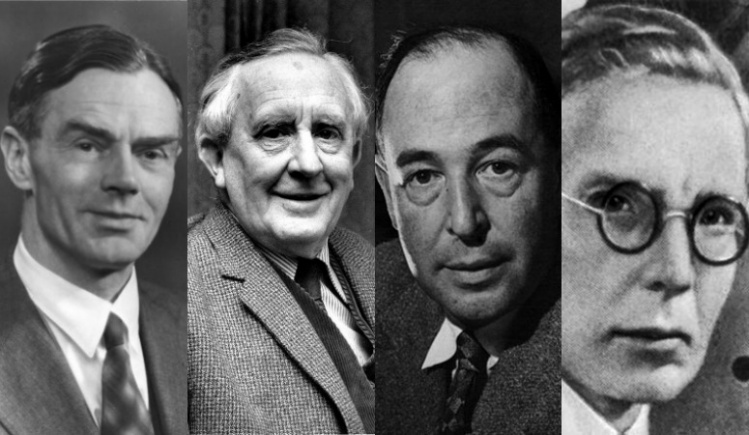

Tolkien fought in World War I, and where he contends that he doesn’t use or like allegory, much of his work is informed by the experiences of his life. In addition, he was a religious man, even co-sponsoring a writing group called the Inklings with C.S. Lewis. The concept of religion and God in The Great War led to his description of Men in The Silmarillion. A few chapters ago, I mentioned that Tolkien’s primary idea with these histories was to eventually tie it back to our Earth (which we caught glimpses of in the chapter last week (Of the Sun and the Moon and the Hiding Valinor). In this chapter, Tolkien tells us how humans were born into a world of ignorance and darkness, yet they strove for the light. As we saw in the quote earlier, Men went west following the Sun, despite their ignorance of its origin.

On top of that, Ulmo tried to get them messages without actually coming back to Middle-earth to inform Men: “and his messages came often to them by stream and flood. But they have not skill in such matters, and still less had they in those days before they had mingled with the Elves. Therefore they loved the waters, and their hearts were stirred, but they understood not the messages.“

I have never met a person who could stand before the Ocean and turn away. The waters bring life to us, and they stir our souls to peace. This connection to the water is what Tolkien was looking for to glue our world with Aman.

Beyond that, Tolkien tells us, “Men were more frail (than the Eldar), more easily slain by weapons or mischance, and less easily healed; subject to sickness and many ills; and they grew old and died.“

We also catch a glimpse of a story yet told; “None have ever come back from the mansions of the dead, save only Beren son of Barahir, whose hand had touched a Silmaril; but he never spoke afterward to mortal Men. The fate of Men after death, maybe is not in the hands of the Valar.”

This paragraph shows Tolkien’s framing of an afterlife, with a Persephone-like callback. Beren dies and then comes back because he has more profound knowledge of the world because of his connection with the Silmaril, which garners its power from The light of the Trees of Valinor. Beren is brought back from the dead through the power of Heaven.

We end the chapter by Tolkien telling us, “those of the Elven-race that lived still in Middle-earth waned and faded, and Men usurped the sunlight.“

Men, the ignorant, had now taken over the world. The magic of the world (the Music of Ainur) began to fade, and a feeling of hard-and-fast reality began to occur.

This chapter is fascinating and tragically beautiful. It is very short (which is why I wanted to discuss various theories rattling around in my brain), but there is perhaps more weight in this chapter than in any previous one.

And where do we go from here? Join us next week as we progress in the story in the next chapter: “Of the Return of the Noldor.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor

“Isil the Sheen the Vanyar of Old named the Moon, flower of Telperion in Valinor; and Anar the Fire-golden, fruit of Laurelin, they named the Sun. But the Noldor named them also Rána, the Wayward, and Vása, the Heart of Fire, that awakens and consumes; for the Sun was set as a sign for the awakening of Men and the waning of the Elves, but the Moon cherishes their memory.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! Instead of continuing on the tale of the Wars of Beleriand, Tolkien takes a step back this week and gives us some worldbuilding. We are prepping for the coming of Man, and this chapter paves the way for that to happen.

The chapter opens by returning us to Valinor and the council of Valar as they try to discern a course of action in the wake of the death of Telperion and Laurelin (the Trees of Valinor).

Yavanna goes to the trees, mourning their passing until she realizes that “Telperion bore at last upon a leafless bough one great flower of silver, and Laurelin a single fruit of gold.“

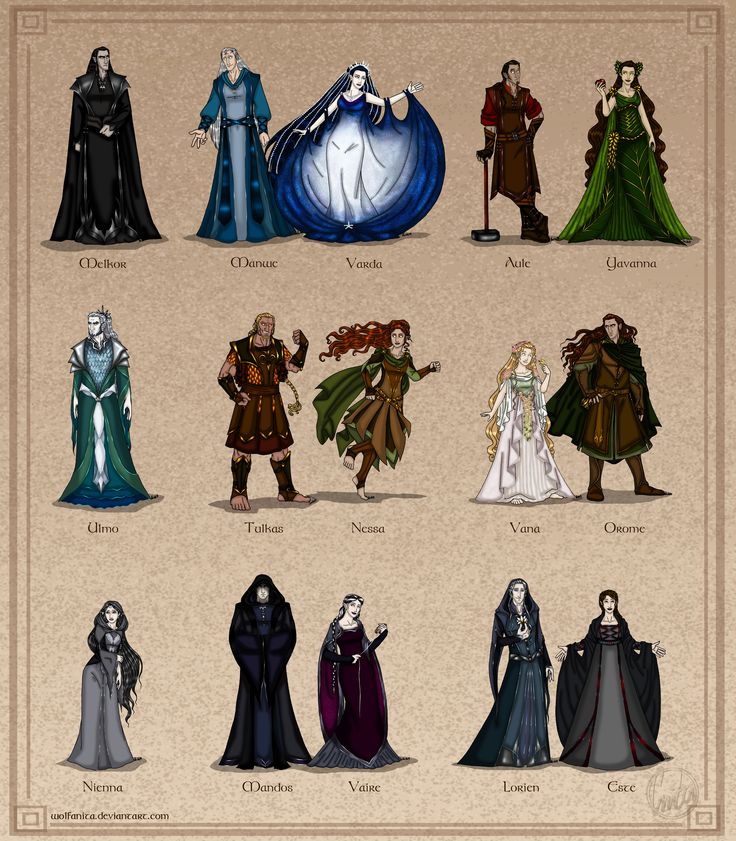

Manwë then hallowed them, and Aulë made a vessel to hold and protect them and their light. These vessels were to “become lamps of heaven,” so the Valar “gave them power to traverse the lower regions of Ilmen.” Ilmen is their word for the sky or the heavens (specifically, Tolkien called it “The region above the air where the stars are” in the name index).

The Valar did so to bring light back to Middle-earth, but also because “Manwë knew also that the hour of the coming of Men was neigh.” Since the Valar went to war with Melkor over the Quendi, they decided that they must then do something for the subsequent children of Ilùvatar. Men were to be mortal, whereas the Elves were not, so as a gift to them, these “lamps of heaven” were to become the Sun and the Moon, which we see in the opening quote of this essay.

We get two understandings from creating these two celestial bodies—the knowledge of mortality and the future sign of the Elves.

We know that Men are mortal, though, in Middle-earth, they had very long lives. But why would men be mortal when all other creatures are immortal (in Aman, beings can be killed at any time, Men are the only ones who have a definitive end to their life span)?

It’s the coming of time.

Before creating the Sun and the Moon, there was no absolute distinction of the passing of time. These started a day and an evening before Men even existed, thus establishing time benchmarks.

Men came into being knowing that there were absolutes, and where Tolkien doesn’t come out and say so (at least not yet), there is little coincidence here because Tolkien chose his wording very carefully.

It is also the first time we see “Earth” in the text instead of using Aman or Eà. I had heard somewhere that Tolkien’s main goal was to tie the history of Middle-earth into our own, so it would make sense that this is an origin story of mythological levels.

The second understanding we get here is the sign of the Elves. The Leaf of Telperion becomes the sign for the Moon or of Twilight. The Elves in Middle-earth prefer to live in Twilight, and we even see this in “The Lord of the Rings” with Arwen, also called Arwen Evenstar. Remember that Tolkien was a linguist, so knowing how we think about language, the phrase “Evening Star” could become the contraction of Evenstar.

The Evenstar is quintessentially recognizable because it’s the trinket that holds her essence, which she gives to Aragorn.

Peter Jackson took some liberties with the movie because here in the text of The Silmarillion; it’s told that the Evenstar, the sign of the Elves, is a “Flower of Silver.“

There is a certain melancholy associated with the Elves because “Evening, the time of the descent and resting of the Sun, was the hour of greatest light and joy in Aman.”

The Elves didn’t like the light; they preferred the Twilight, which could be why they called the land in Valinor “The Grey Havens.” It was not to indicate depression, but of a final blessing, the last light to be with the Valar in Valinor where they are meant to be. The Grey Havens are almost a moniker for Heaven. The phrasing is so close that it’s hard to refute.

But it was also during this time that Heaven became challenging to attain. The Valar became concerned for Valinor because of Morgoth’s wrath. He settled into his rage, and the Valar finally came to realize that Morgoth was intractable; thus, they created a barrier around Aman:

“But in the Calacirya they set strong towers and many sentinels, and at its issue upon the plains of Valmar a host was encamped, so that neither bird nor beast nor elf nor man, nor any creature beside that dwelt in Middle-earth, could pass that leaguer.“

Thus the creed of Mandos we saw two chapters ago became true:

“Thus it was that as Mandos foretold to them in Araman the Blessed Realm was shut against the Noldor; and many messengers that in after days sailed into the West none came ever to Valinor – save one only: the mightiest mariner of song.“

So how does Fëanor take this? Does he get along with the new children of Ilùvatar, Men?

Find out next week in “Of Men.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of the Sindar

“And when the building of Menegroth was achieved, and there was peace in the realm of Thingol and Melian, the Naugrim yet came ever and anon over the mountains and went in traffic about the lands; but they went seldom to the Falas, for they hated the sound of the sea and feared to look upon it. To Beleriand there came no other rumour or tidings of the world without.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we take a step back from the Noldor and look at their Kin, the Sindar, who remained in Beleriand and forsook the light of Valinor. We also get a look at a brand new race, only glanced over in previous chapters.

This chapter looks to fill in the blanks from what transpired on Beleriand during the ages of Melkor on Valinor. In the first few sentences, Tolkien informs us of another famous legend of Middle-earth; a child of Eldar and Maiar. Next, we find that “at the end of the first age of Melkor… there came into the world Lùthien, the only child of Thingol and Melian.”

I don’t know much about Lùthien, but I know that she loved Beren and had such a well-known story; it’s even told during “The Lord of the Rings.” The good news is we won’t have to wait long because their tale is Chapter 19 in The Silmarillion.

This chapter goes back to the more complex language, as it’s more exposition than storytelling; however, I find it fascinating how many little details Tolkien inserts throughout the text. They are barely mentioned, but they give flavor to the world and take higher importance in “The Lord of the Rings.” For example:

“and there in the forest of Neldoreth Lùthien was born, and the white flowers of niphredil came forth to greet her as stars from the earth.”

The niphredil is a white flower that bloomed only in the moonlight with Lùthien’s birth, but they were also in Lothlorien during “The Fellowship of the Ring.”

These are the connections I was hoping to find in this project. They may be small and seemingly insignificant, but they bring together the world in such a way that makes it a cohesive history rather than just a series of tales. I’ll continue to point these little nuggets out as best as I can from my current understanding of the history of Middle-earth and its environs.

Back to the story:

“It came to pass during the second age of the captivity of Melkor that Dwarves came over the Blue Mountains of Ered Luin into Beleriand. Themselves they named Khazâd, but the Sindar called them Naugrim, the Stunted People, and Gonnhirrim, Masters of Stone.”

The Dwarves earned that name because they delved into the mountains, more specifically Ered Luin on the eastern side of Beleriand. There they built (or instead dug) their massive cities, Gabilgathol and Tumnunzahar, but the “Greatest of all the mansions of the Dwarves was Khazad-dûm, the Darrowdelf, Hadhodrond in the Elvish tongue, that was afterwards in the days of its darkness called Moria.”

If you are reading this essay, you know what Moria is and will be, as it’s central to The Fellowship of the Ring, but what’s noticeably absent is the animosity the Dwarves and Elves feel for each other. There is even a passage where Tolkien tells us: “but at that time those griefs that lay between them had not yet come to pass…”

The Dwarves were eager to learn the Elvish tongue, and even though the Naugrim (Dwarven) tongue was “cumbrous and unlovely.” the Elves learned it back as well.

They trafficked goods with each other and praised one another. Then, after years of this communion, Melian “councelled Thingol that the Peace of Arda would not last for ever.”

So Thingol sought council with the Dwarves, and they agreed to dig him out of a dwelling for protection against a possible incursion from Morgoth and his minions. They called this underground mansion Menegroth or the Thousand Caves.

They did it at the right time because “…ere long the evil creatures came even to Beleriand, over passes in the mountains, or up from the south through the dark forests.”

Of course, there are Orcs, but we also see new creatures, Wolves and Werewolves. Seeing these new and horrid creatures, the Dwarves made for the Elves armor, which”surpassed the craftsmen of Nogrod, of whom Telchar the smith was greatest in renown.”

The Sindar drove off the creatures of darkness with the help of the “war-like” Dwarves. For a time, there was peace. Then, Denethor gathered the Elves who did not make the journey into Beleriand (no, not that Denethor. This is an Elf, Son of Lenwë, and a chieftain of nomadic/hunter-gather elves.) and brought to Menegroth.

During this gathering and goodwill, Morgoth and Ungoliant were busy fleeting Valinor and soon headed east to clash with King Thingol and the Thousand Caves. Orcs descended upon Menegroth in ferocity, and there was “fought the first battle in the Wars of Beleriand.“

The Elves were victorious, but so brutal and quickly spawning the Orcs were, that Melian had to use some of her Maiar powers and formed “the Girdle of Melian, that none thereafter could pass against her will or the will of King Thingol.” They were thus protected, but unfortunately, outside of the field, the creatures of Morgoth roamed free.

But across the seas, things were stirring. It was just after the Girdle of Melian was created that Fëanor and his host made their way to Beleriand.

Now we have three forces coming together, and thinking back on the “Questionable decisions” Fëanor made that forced his wife from him, I have to wonder if this firey elf caused the Wars of Beleriand. Could he be the reason the Dwarves and Elves dislike each other? Could he be the cause of the Wars of Beleriand altogether?

Next week, let’s find out in “Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor.”

Post Script:

I had some difficulty with this chapter because my time frame kept getting confused. That’s because Tolkien uses “ages” as a time sobriquet. This chapter had the “first age of Melkor’s chaining.” which is different from the “first age of the Valar” and even more different from “the first age of man” or the “First age of Èa.”

It takes a minute to dig down into what’s happening, but this is Tolkien’s definition of time. The way he wrote these histories they were short stories he framed (or rather his son, Christopher, did) into a larger spectrum. So for his brain to formulate the times, they were ages, and the events could happen within those ages. We haven’t gotten to the language or time of Tolkien, but both of those will need individual essays.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion; Of the Flight of the Noldor

“Fëanor was a master of words, and his tongue had great power over hearts when he would use it; and that night he made a speech before the Noldor which they ever remembered. Fierce and fell were his words, and filled with anger and price; and hearing them the Noldor were stirred to madness. His wrath and his hate were given most to Morgoth, and yet well nigh all that he said came from the very lies of Morgoth himself; but he was distraught with grief for the slaying of his father, and with anguish for the rape of the Silmarils.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we delve into the mindset of the Noldor as they divest themselves from the rest of the Eldar. We’ll also catch a glimpse of a very well-known Noldor, and we’ll get a greater understanding of Fëanor’s motivations.

We begin this chapter right where the last one left off. Melkor and Ungoliant killed the Trees of Valinor and fled Aman. Yavanna, the Valar who created the Trees, mourns them but comes to realize, “The Light of the Trees has passed away and lives now only in the Silmarils of Fëanor. Foresighted was he!”

Yavanna asks him to give up his Silmarils because “had I but a little of that light I could recall life to the Trees.”

He was excited at this prospect, but many Valar pressured Fëanor to relinquish his prized creations. Still, Fëanor ponders this option until the deception of Melkor, which we learned of in chapter 7, comes back into Fëanor’s mind; it was all a trick. Wasn’t Melkor, now Morgoth, Valar as well? Was this just an elaborate scheme to get Fëanor to give up his creation?

But it was not a trick, and in the darkness, Morgoth returned and “slew Finwë King of the Noldor before his doors, and spilled the first blood in the Blessed Realm.” This single act solidified Morgoth’s transition to evil as he broke into the stronghold of Formenos and stole the Silmarils.

He then fled with Ungoliant across the frozen strait of Helcaraxë, which separated Aman (Valinor) from Middle-earth. Ungoliant demanded that Morgoth feed her the gems he stole, but he held back the Silmarils, and as punishment to him, “she enmeshed him in a web of clinging thongs to strangle him.” He was stuck there in a land which would be called Lammoth, “for the echoes of his voice dwelt there ever after, so that any who cried aloud in that land awoke them, and all the waste between the hills and the sea was filled with a clamour as voices in anguish.”

These cries woke the Balrogs who rested beneath Angband (Morgoth’s domain) and came with their flame whips to “smote the webs of Ungoliant asunder” and frightening her enough to flee.

She took shelter in Nan Dungortheb in the north of Middle-earth (then Beleriand) and mated with the giant spider creatures which lived there. After that, it is unknown what happened to Ungoliant, though “some have said that she ended long ago, when in her uttermost famine she devoured herself at last.“

On the other hand, Morgoth fled to Angband and grew his army of Orcs (made from corrupting Elves) and demons and beasts and made himself a crown of iron which he inlaid the Silmarils.

“His hands were burned black by the touch of those hallowed jewels, and black they remained ever after; nor was he ever free from the pain of the burning, and the anger of the pain.“

This pain fueled his hatred and made him an even more significant threat to the tenants of Ea.

Here we catch a page break and switch gears. Here, the quote that begins this essay appears, and we spend the rest of the chapter discovering why the Noldor left Valinor and the strife that arose amongst them.

What is interesting about this chapter is that Fëanor, who hates Morgoth more than anything else in the world, falls right into his trappings. All the lies Morgoth whispered to the Noldor somehow seep into his mind, and he stands before his kin and starts a revolution. He does from anger because of the loss of his father and the loss of his creations, the Silmarils. Remember in the chapter that describes the design of the Silmarils. These gems have much the same hold over people as the One Ring does in the Third Age. We have not yet seen the power that they can produce, but could it be that the loss of these gems has clouded Fëanor’s mind? Could this be their power represented without Tolkien coming right out and telling us?

In any case, Fëanor rallies his kin to take “…an oath which none shall break, and none shall take, by the name even of Ilùvatar, calling the Everlasting Dark upon them if they kept it not; and Manwë they named witness, and Varda, and the hallowed mountain of Taniquetil, vowing to pursue with vengeance and hatred to the ends of the World Vala, Demon Elf or Man as yet unborn, or any creature, great or small, good or evil, that time should bring forth unto the end of days, whoso should hold or take or keep a Silmaril from their possession.”

But there was friction amongst their ranks. The sons of Fëanor were staunchly in his corner. Still, Fëanor’s brothers, Finarfin and Fingolfin, disagreed with his harsh sentiments, but they stayed true to their course since they had already joined him in their departure. So they left Valinor, but they and their host left the company of Fëanor and his followers.

This chapter is much more accessible than previous chapters because the dialogue reveals Noldor’s desires. First, they bicker and argue about the best way to do things, and eventually, they split; though the endgame of their intentions is to destroy Morgoth, they go about it differently.

Fëanor uses some of his firey drive and uses the questionable decisions his wife left him for and stole the only ships which can make their way to Beleriand. In the process, they murder some of the Teleri who created the ships, only to flee the land.

His kin is left with no other option but to take the same path as Morgoth and Ungoliant and travel across the frozen pass, Helcaraxë. Unfortunately, many of them die from the passage through the icy straits, which deepened their disdain for Fëanor.

The Noldor became outcasts because of this sundering. They left the land they struggled so hard to get to because of misunderstanding, fear, and desire, and we are left wondering what is to come of the Noldor afterward because of a passage delivered by Mandos, a herald of Manwë:

“Tears unnumbered ye shall shed; and the Valar will fence Valinor against you, and shut you out, so that not even the echo of your lamentation shall pass over the mountains. On the house of Fëanor the wrath of the Valar lieth from the West unto the uttermost East, and upon all that will follow them it shall be laid also. Their Oath shall drive them, and yet betray them, and ever snatch away the very treasures that they have sworn to pursue. To evil end shall all things turn that they begin well; and by treason of kin unto kin, and the fear of treason, shall this come to pass. The Dispossessed shall they be forever.”

Some tales delve deeper into every transgression the Noldor did during this time. They are collected in a “lament which is named Noldolantë, the Fall of the Noldor.” Still, I’m beginning to wonder if these little offshoots are actually written down in other books like “The Book of Lost Tales” or if this is just a little flavor of history that Tolkien wanted to tell but never got around to completing. In any case, I’m very excited to see where the story goes next because we’ve transcended the Biblical style voice the beginning of this book held and have transitioned into a more storyteller fashion.

Will we finally get to see the fate of Fëanor and the Noldor next week? Join me as we review “Of the Sindar.”

PostScript.

I promised that we’d see a familiar face, and I was shocked at the character-building Tolkien was able to instill in a single paragraph:

“Galadriel, the only woman of the Noldor to stand that day tall and valiant among the contending princes, was eager to be gone. No oaths she swore, but the words of Fëanor concerning Middle-earth had kindled in her heart, for she yearned to see the wide unguarded lands and to rule there a realm at her own will.“

Galadriel held a wonder of the wider world to see, experience, and travel. Her curiosity about what life truly means drives her to leave Valinor to go to Beleriand.

It’s more than that, however. Galadriel wanted to be a queen in her own right. She had grown up and seen how the Noldor clung to history and tradition, even to their detriment. This was Galadriel’s time to make a mark. Unfortunately, I’ve not seen her past outside of the books and movies, and it’s been so long since I’ve read the books that I’m sure I’m missing something there, but even so, I hope she is a feature in the remaining story.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion; Of The Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor

“Thus with lies and evil whisperings and false council Melkor kindled the hearts of the Noldor to strife; and of their quarrels came at length the end of the high days of Valinor and the evening of its ancient glory. For Fëanor now began openly to speak words of rebellion against the Valar, crying aloud that he would depart from Valinor back to the world without, and would deliver the Noldor from thraldom, if they would follow him.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we inch forward through the history of the elves and get a deeper glimpse into the transgressions of Fëanor.

Last week we learned a bit about the Fëanor’s lineage and how much he progressed beyond his fellow elves. We dig down deeper into Fëanor this week and understand why his wife, Nerdanel, finally ended their relationship.

It’s important to know that Fëanor, the “heart of fire,” emerged as one of the most brilliant of the Noldor, not only in intelligence but in construction, learning much and creating even more. It’s at the beginning of this chapter that we discover a new and exciting revelation:

“In that time were made those things that afterwards were most renowned of all the works of the Elves. For Fëanor, being come to his full might, was filled with a new thought, or it may be that some shadow of foreknowledge came to him of the doom that drew near; and he pondered how the light of the Trees, the glory of the Blessed Realm, might be preserved imperishable. Then he began a long and secret labor, and he summoned all his lore, and his power, and his subtle skill; and at the end of all, he made the Silmarils.”

Ah, here it is! I’ve been waiting to see what the Silmarils are and what they have to do. But unfortunately, we don’t get much information, even in this chapter of their creation. Still, it’s good to know that Fëanor created them, using all the guile he developed from the Valar, and harnessing the light of the two trees of Valinor:

“And the inner fire of the Silmarils Fëanor made of the blended light of the Trees of Valinor, which lives in them yet, though the Trees have long withered and shine no more.”

The Valar were so taken with the “wonder and delight at the work of Fëanor” that “Varda hallowed the Silmarils, so that thereafter no mortal flesh, nor hands of unclean, nor anything of evil will might touch them” and also that “the fates of Arda, earth, sea, and air, lay locked within them.“

So we know immediately that something of that magnitude must have others who crave its power. “Then Melkor lusted for the Silmarils, and that very memory of their radiance was a gnawing fire in his heart.”

Melkor had been released on “good behavior” from his imprisonment but still held that anger in his heart (which we saw last week), but he doesn’t come right out and wage war to get the stones. Instead, he uses a much more subsumed tactic and begins spreading rumors amongst the Noldor:

“Visions he would conjure in their hearts of the mighty realms that they could have ruled at their own will, in power and freedom in the East.“

These visions were the first wedge in the rift between the Eldar and the Valar. Rumors abounded that the Valar were jealous of the Eldar ruling themselves, and that’s why they were brought to Valinor so that they might be subjects instead of free people.

In addition to that, the Eldar (elves) didn’t know about the coming of Men, so Melkor used this lack of knowledge and put thoughts within the Eldar’s heads that the Valar would call Men to the world to supplant them.

This Melkor did to the Elves in general because of his hatred for them, but Fëanor was the focus of his ardor because of the Silmarils, which Fëanor would flaunt and wear; he kept them to himself. In fact, “Fëanor began to love the Silmarils with a greedy love and grudged the sight of them to all save to his father and his seven sons; he seldom remembered now that the light within them was not his own.“

This passage reminds me of something else we’ll see later in the Second and Third Ages. The One Ring. Something with such power and wonder makes people subject to its will.

The influence of the Simarils and the whisperings of Melkor caused the quote at the beginning of this essay. Fëanor created incredible weapons and armor at his secret forge and spoke out against his half-brother Filgolfin and drove him from the house.

Strife billowed out from the house of Finwë (Fëanor’s father), and finally, the Valar understood the unrest brewing within the Noldor. The problem was “since Fëanor first spoke openly against them, they judged that he was the mover of discontent.“

They held a council and found that Melkor was indeed who began the conflict. However, Fëanor still had to answer for the strife he caused, so he was moved to the north of Valinor into the mountains where he had a vault any Dwarf would be proud of, complete with an iron vault that held the Silmarils. This incident was the beginning of the rift between the sons of Fingolfin (Elrond’s ancestor) and Fëanor, which lasted for generations.

Melkor, trying to extend his deception and get a hold of the Silmarils, went to Fëanor and tried to continue his illusion. Still, if you remember from the last chapter, Fëanor held only hatred for shifty Valar, and he banished Melkor (whom Fëanor named Morgoth) from his home. Not having much choice, Melkor fled Valinor back to Araman, giving false hope to all those who dwelt in Valinor, for the shadow moved beyond their vision and grew. To what end?

Next week, let’s find out while we review the chapter “Of the Darkening of Valinor.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion; Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor

“Then he looked upon their glory and their bliss, and envy was in his heart; he looked upon the Children of Ilùvatar that sat at the feet of the Mighty, and hatred filled him; he looked upon the wealth of bright gems, and he lusted for them; but he hid his thoughts, and postponed his vengeance.“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we focus on an individual and witness the beginning of the rift, which brought the first age to a close.

The chapter begins right where the previous one left off. The Elves were all brought together in Valinor, seemingly happy and together for the first time since the sundering. “This was the Noontide of the Blessed Realm, the fullness of its glory and its bliss, long in tale of years, but in memory too brief.”

This quote seems very appropriate for Elvenkind because they live forever (unless killed), but time does the same thing to everyone. Life passes by quickly, unbeknownst until the time is already gone. I wonder if there is a bit of autobiography here with Tolkien and if his feelings about life and time commingle with the complexity of Middle-earth and Elves.

We soon dive into the reasoning behind this feeling of how long and beautiful and how fleeting life can be.

“In that time was born in Eldamar, in the house of the King in Tirion upon the crown of Tùna, the eldest of the sons of Finwë, and the most beloved. Curufinwë was his name, but by his mother he was called Fëanor, Spirit of Fire; and thus he is remembered in all the tales of the Noldor.”

Thus began days of bliss, but “bearing of her son Míriel was consumed in spirit and body,” and she soon realized that, “Never again shall I bear child; for strength that would have nourished the life of many has gone forth into Fëanor.” She left for the gardens of Lórien to rest but instead passed from the world of Aman.

There is considerable foreshadowing in this sequence. The first is Finwë’s name, Fëanor, because it means Spirit of Fire. The other being that we know of so far in the whole book who has a connection with fire is Melkor; and even created servants for himself through the Maiar made from the deepest of flames – the Balrog.

We also have a trope that Tolkien is introducing. Fëanor has lost his mother and has to deal with the knowledge that his birth pulled the life force from his mother. His internal guilt fuels that Spirit of Fire within him, but beyond that, Finwë then finds another wife not of the Noldor but the Vanyar. Fëanor then has two siblings from a different sect of elves and has a new stepmother.

Finwë did try hard; in fact, we are told, “All his love he gave thereafter to his son.” Fëanor soon “became of all the Noldor, then or after, the most subtle in mind and the most skilled in hand.” Fëanor even “discovered how gems greater and brighter than those of the Earth might be made with skill.”

This essay is a Blind Read, so the only knowledge I have of the world is from the public ethos and reading The Lord of the Rings (which I read before the movies came out). Nevertheless, I remember hearing that the Silmarils (which is what this book is based upon…The Silmaril-lion) were gems the Elves held dear. Could this be the first time we see them?

There is also a connection with the avian creatures which pop up. However, again, “The first gems that Fëanor made were white and colourless, but being set under starlight they would blaze with blue and silver fires brighter than Helium; and other crystals he made also, wherein things far away could be seen small but clear, as with the eyes of the eagles of Manwë.” So there must be some connection between the sentience of the eagles and the gems produced by the Noldor.

Getting back to the story, Fëanor eventually marries Nerdanel, “daughter of the great smith named Mahtan.” “Nerdanel also was firm of will…and at first she restrained him when the fire of his heart grew too hot; but later his deeds grieved her, and they became estranged.” Fëanor and Nerdanel had seven children together, but even that connection was not enough for Fëanor, and his temperament burned too intensely.

Fëanor hotly disliked his two new siblings, Fingolfin and Finarfin, who sired Elrond and Galadriel, as we saw last week. As we move deeper in the story, we can assume this might be where the rifts came from between Fëanor and Nardanel and Fëanor and the rest of the Noldor.

We soon came to the end of the Noontide of Valinor, as Melkor came up for parole (or rather, the Valar gave him a definite “term for his bondage“). However, still, “hatred filled him” and “envy was in his heart.”

How could the Valar possibly do such a thing, you might ask? Nevertheless, Manwë was the one who gave Melkor his release because he believed “that the evil of Melkor was cured.“

How could he possibly believe that imprisonment had cured Melkor? “For Manwë was free from evil and could not comprehend it, and he knew that in the beginning, in the thought of Ilúvatar, Melkor had been even as he; and he saw not the depths of Melkor’s heart and did not perceive that all love had departed from him forever.”

So now Melkor was free. He knew that some of the Valar, like Ulmo, did not believe his repentance, but he hid his vengeance well. He hated the Eldar with everything he had, so he started corrupting them. The Vanyar, however, “held him in suspicion,” but the “Noldor took delight in the hidden knowledge that he could reveal to them; and some hearkened the words that it would have been better for them never to have heard.”

Uh oh. Now we have Melkor released and Fëanor with his soul filled with fire. Would these two spar together and become a new power rising? No.

“Melkor indeed declared afterwards that Fëanor had learned much art from him in secret, and had been instructed by him in the greatest of all his works; but he lied in his lust and his envy, for none of the Eldalië ever hated Melkor more than Fëanor son of Finwë, who first named him Morgoth.“

Apparently, “Fëanor was driven by the fire of his own heart only, working ever swiftly and alone.”

This is where the chapter ends, but we have the beginnings of a wonderfully epic confrontation between the Noldor and Morgoth. From what I understand, Morgoth was the antagonist of the First Age, and it seems as though I may have been wrong. Maybe the power of the fire of Fëanor’s soul is the only thing that saved the Eldar from the matching fire of Morgoth.

Next week, let us find out how the fight began in “Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of Thingol and Melian

“In after days, he became a king renowned, and his people were all the Eldar of Beleriand; the Sindar they were named, the Grey-elves, the Elves of Twilight, and King Greymantle was he, Elu Thingol in the tongue of that land.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we have a concise chapter, so I thought it would be the perfect time to review and dig into theories about what we’ve read so far in The Silmarillion.

This chapter follows Melian, a Maiar (the servants of the Valar), and Elwë, the Lord of the Teleri, whom we saw in the last chapter.

Melian “dwelt in the gardens of Lórien, and among all his people there were none more beautiful than Melian, nor wiser, nor more skilled in songs of enchantment.” She came to middle-earth at the same time as Yavanna, “and there she filled the silence of Middle-earth before the dawn with her voice and the voices of her birds.”

The Teleri who “tarried on the road.” across Middle-earth to Valinor were led by Elwë and Olwë, two brothers. Elwë Singollo, which surname we found in the previous chapter signifies Greymantle, heard the song of the lómelindi (the Nightingales), and in that song he heard the beautiful voice of Melian.

He set out to follow that song, and in doing so, “He forgot then utterly all his people and all the purposes of his mind,” and he was lost in the forest. He met Melian there, lost under the twilight stars, “and straightaway, a spell was laid on him.” He had fallen deeply in love with her and stayed with her in eastern Beleriand, starting their own faction of Eldar, which is what we see in the opening quote of this essay. He became Elu Thingol, King Greymantle of the Sindar, where Olwë, his brother, assumed kingship of the Teleri in his absence and took them to Valinor.

“And of the love of Thingol and Melian there came into the world the fairest of all the Children of Ilùvatar that was or shall ever be.” Namely the Sindar, or Grey-elves.

That is the chapter; not a lot to it, but there are some key points here to latch onto and I’d be remiss if I didn’t touch on them. First, we are currently discovering the creation of the peoples of Middle-earth at this point known as Beleriand (from my basic knowledge, Beleriand was sundered in the wars of the first age, which I’m sure will be covered in the remaining text of the Silmarillion.)

The first point I’d like to discuss is song. There was much made of music and song in Peter Jackson’s seminal trilogy and even more in the text of the books. There were characters like Tom Bombadil who basically spoke in music (and I’m inquisitive to see if we get a glimpse of where he came from), poems, and songs sung throughout the books, culminating in Pippin’s song near the end of Return fo the King.

Song and music are rampant throughout Tolkien’s world, and it wasn’t until I began this journey into The Silmarillion that I began to notice that there is a reason behind this. Music is the cornerstone of life; it’s what brings the people of Middle-earth life and happiness and sorrow. Indeed the entire world was built by song…The song of the Valar and Ilùvatar. The music that we’ve all experienced while traversing this incredible creation is an offspring of this idea. The old themes are sung to elicit feeling and emotion and give a glimpse of the past and the future. There is a theory that all music is derivative; all music comes from just a few early and core songs. This shows more gloriously here than anything else because all music portrayed echoes past, an echo of the songs sung by the Valar as the world was being created. One must assume that they all have their own tone and theme incorporated into their song, as varied as a love of nature to the agony of war. The pieces of this music are what create the world and the destination of those within it. I’m so excited to see what other music or song is incorporated moving forward.

The second point I wanted to touch on was language. Tolkien famously created this world based on language, and everything else came from that. This is what makes The Silmarillion so hard to read because there are multiple names for each character and sobriquets based upon whom they interact with. However, the more I dig into the history, the more I’m beginning to understand the language (with the help of the index, of course). Once you come across a name (like Beleriand, the land beyond the bay of Balar), if you’ve paid attention to the core of the word, there’s a good chance you’ll understand where the story is going to go surrounding that character.

The best example of this I can imagine is the introduction of Elwë Singollo. Immediately we are told that Singollo indicates the Greymantle, then everything that follows points towards the creation of the Grey Elves. The Nightingales sing at Twilight, the grey mist when Thingol and Melian meet, right down to their children and followers tribe name…Sindar, which is a derivative of Singollo. They are the Grey Elves, not because of their skin color, but because they were not of the light, meaning that they never went to Valinor, nor are the Sindar from the Dark; they are Elves of Twilight, both of time and location. It is these nuggets I’ll work to uncover as we continue on throughout this blind read.

What will we uncover next?

Join me next week as we move into “Of Eldamar and the Princes of the Eldalië!”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor

“Yet be sure of this: the hour approaches, and within this age our hope shall be revealed, and the Children shall awake. Shall we then leave the lands of their dwelling desolate and full of evil? Shall they walk in darkness while we have light? Shall they call Melkor lord while Manwë sits upon Taniquetil?“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week the First of Ilùvatar’s Children (Elves) awaken, Melkor is thwarted, and we get some in-depth understanding of the creation of Middle-Earth, its peoples, and its antagonists.

We begin this chapter of the history of Middle-earth by finding that the Valar grew comfortable with their creations. Melkor was defeated, and they put him out of their minds, staying away from his lands and “the evil things that he had perverted.” Melkor created a stronghold, commanded by his lieutenant, Sauron (sound familiar?), named Angband. It was here we find the perverted things including the Maiar who followed him: “those spirits who first adhered to him in the days of his splendour, and became most like him in his corruption: their hearts were of fire, but they were cloaked in darkness, and terror went before them; they had whips of flame. Balrogs they were named in Middle-earth in later days.”

This is where we get the opening quote of this essay. The Valar, on their seats in Valinor, had a great debate on what to do with Middle-earth and the impending Awakening of the first Children of Ilùvatar, the Elves.

Varda, Manwë’s spouse, decided that the Elves should not be born into the darkness that blanketed Middle-earth, so she created the stars (which is why the Elves then called her Elentári in their tongue means ‘Queen of Stars’). I’ll leave the passage for this in the postscript because several names aren’t pertinent to this portion, but I have a sneaking suspicion they will be later!

Anyway, the Elves woke next to Cuiviénen (a lake in Middle-earth, otherwise known as “The Water of Awakening“), and the first thing they saw were the beautiful stars and “Long they dwelt in their first home by the water under the stars...” They even developed their own speech, then naming themselves the Quendi, “signifying those that speak with voices” as the Valar had no need for voice.

These Children of Ilùvatar were “stronger and greater than they have since become;” and the Valar decided that they needed to get these children to join them in Valinor, so Oromë had them follow him back, and those that did he named the Eldar, or the people of the stars.

But why didn’t they all follow Oromë, you ask? Melkor put stories into their heads to scare them off from the great hunter. Reports of “a dark Rider upon his wild horse that pursued those that wandered to take and devour them.” Melkor was able to ensnare some of these unfortunate Elves by this deception, and “those of the Quendi who came into the hands of Melkor, ere Utumno was broken, were put there in prison, and by slow arts of cruelty were corrupted and enslaved; and thus Melkor breed the hideous race of the Orcs in envy and mockery of the Elves, of whom they were afterwards the bitterest foes.“

So Melkor created Orcs from the Elves, but not just from the Elves… from the Quendi, who were stronger and greater than what the Elves later became. So it makes sense why the Orcs are thought of as so terrifying.

Understanding that Melkor was gaining in power the Valar decided that they must do something about it, so they decided to ride out against Melkor and capture him; to save the Quendi from the spread of his darkness. Apparently little is known of this battle because it didn’t take place in the view of the Quendi, except that “the Earth shook and groaned beneath them, and the water moved, and in the north there were lights as of mighty fires.”

The battle was so savage that the shape of the land itself was altered permanently, but eventually Melkor “was bound with the chain Angainor that Aulë had wrought, and led captive; and the world had peace for a long age.” The Valar discovered and defeated many of the ranks of Melkor, but they never did find his lieutenant, Sauron.

The world was at peace, and after long years of discussion, the Valar decided that the Quendi should join the Valar in Valinor far to the west. They sent for Ingwë, Finwë, and Elwë, who were ambassadors of the Elves and later became their kings, but free will got in the way.

“Then befell the first sundering of the Elves.”

The kindreds of these ambassadors followed Oromë to the west and became known as the Eldar. The ones who stayed behind loved their home of Middle-earth, the seas, the trees, and the stars and they refused the summons. These Elves became known as the Avari, or the Unwilling.

But beyond this first sundering, even the Eldar split as well. The three different ambassadors had their own followers, each with their own predilections. The followers of Ingwë were known as the Vanyar, or the Fair Elves, who are closest to the Valar and few men have ever seen.

Then there are the Noldor, the people of Finwë, otherwise known as the Deep Elves, who were known as great fighters and laborers.

Lastly there were the followers of Elwë Singollo (Singollo signifies Greymantle. I have a feeling we’ll find more out about that next week!), who were named the Teleri, who “tarried” on the roads and were the last to appear in Valinor. They are known as the Sea Elves, or Falmari, because of their love for the sea and making music beside the breaking waves.

These three kindreds of Elves who made it to Valinor are called the Calaquendi, or Elves of the Light (or a very literal translation, “Those who speak of the light“)

These Elves do not take much part in the story of the Silmarillion, but rather those they left behind, those that the “Calaquendi call the Umanyar, since they came never to the land of Aman and the Blessed Realm.” These Umanyar and the Moriquendi (or the Elves of Darkness who came later and “never beheld the Light that was before the Sun and Moon.” are who the remaining history of Middle-earth pertains to.

The Nandor, who were led by Lenwë and “forsook the westward march, and led away numerous people, southwards down the great river, and they passed out of the knowledge of their kin for long years were past.” until years later Denethor (not to be confused with Denethor II the steward of Gondor from the Third Age. Aka, father to Boromir and Faramir), son of Lenwë, decided to lead his people west over the mountains and into Beleriand (the westernmost land of Middle-earth).

We have finally gotten past the rich history of gods and angels and are getting into the creation of Middle-earth as we know it. I’m most curious to see where the coming of men, the second of the Children of Ilùvatar, come into play as the Elves begin to build their roots in the land. Do you have an idea of where we’re headed?

Let’s find out next week as we discover “Of Thingol and Melian.“

Post Script:

As promised, here is your passage…

“Then Varda went forth from the council, and she looked out from the height of Taniquetil, and beheld the darkness of Middle-earth beneath the innumerable stars, faint and far. Then she began a great labor, greatest of all the works of the Valar since their coming into Arda. She took the silver dews from the vats of Telperion, and there-with she made new stars and brighter against the coming of the First-born; wherefore she whose name out of the Deeps of Time and the labours of Eä was Tintallë, the Kindler, was called after by the Elves Elentári, Queen of the Stars. Carnil and Luinil, Nénar and Lumbar, Alcarinquë and Elemmírë she wrought in that time, and many other of the ancient stars she gathered together and set as signs in the heavens of Arda: Wilwarin, Telumendil, Soronúmë, and Anarríma; and Menelmacar with his shining belt, that forbodes the Last Battle that shall be at the end of days. And high in the North as a challenge to Melkor she set the crown of seven mighty stars to swing, Valacirca, the Sickle of the Valar and sign of doom.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of Aulë and Yavanna

“But I will not suffer this: that these should come before the Firstborn of my design, nor that thy impatience should be rewarded. They shall sleep now in the darkness under stone, and shall not come forth until the Firstborn have awakened upon Earth; and until that time thou and they shall wait, though long it seem. But when the time comes I will awaken them, and they shall be to thee as children; and often strife shall arise between thine and mine, the children of my adoption and the children of my choice.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we continue on the journey through the Quenta Silmarillion, learn about a few new races of beings, and discover the evolution of life in Middle-earth!

This second chapter is short and answers a question I’d been wondering since we started the journey through this history: Where did Dwarves come from?

Through the first few chapters as we got to know the beginning of Middle-earth we came to understand that Ilùvatar created his own children, the Elves and Men. There were so many other races not represented here which had me questioning their origins, none more than Dwarves. The Dwarves of Middle-earth are a prideful and powerful bunch and knowing just a bit about their history with Elves, I wondered where and how they came into the story.

Well this chapter starts us off in the first sentence: “It is told that in their beginning the Dwarves were made by Aulë in the darkness of Middle-earth; for so greatly did Aulë desire the coming of the Children, to have learners to whom he could teach his lore and his crafts, that he was unwilling to await the fulfillment of the designs of Ilùvatar.“

So Aulë created the dwarves at the same time Elves and Man were being created, and “because the power of Melkor was yet upon the Earth” he made the Dwarves “stone-hard, stubborn, fast in friendship and in enmity.” He also made their lives long, longer than Men, but not eternal like the Elves.

When he created them (in the true fashion of Prometheus disobeying Zeus and giving humans fire), Ilùvatar was angered, because he had yet to finish creating his own children; but when Aulë showed that he was willing to smite them with his hammer, Ilùvatar took pity on them and we get the opening quote of this essay.

Aulë had promised the Dwarves they would sit at the End of the World with the Children of Ilùvatar, led by the Seven Father’s of Dwarves, “of whom Durin was the most renowned in after ages, father of that kindred most friendly to the Elves, whose mansions were at Khazad-dûm.” In case you don’t recognize this name from either the books or the movies, the better known name for Khazad-dûm is The Mines of Moria.

So now we know the Dwarves were created by Aulë as the “Second Born.” and were sequestered in Moria to await the coming of the First Born, aka the Children of Ilùvatar, aka Elves and Men.

But what of Yavanna? We’ve only spoken of Aulë and the chapter head has both of their names! Well, because Aulë kept his creations a secret even from Yavanna, the Dwarves ended up not caring much about her creations, instead, “they will love first the things made by their own hands, as doth their father. They will delve in the earth, and the things that grow and live upon the earth they will not heed.“

Yavanna was afraid for her great creation…nature. The bountiful trees and the beautiful forests were potentially in danger, because of the nature of Aulë, the smith, he instilled in his children that they should be desirous of making their own creations through industry. If Melkor got his desires into these industrial Dwarves, what was to stop them from cutting down Yavanna’s beautiful forests to use in their production?

Yavanna went to Manwë, the Valar of Wind and Sky and spoke her fears:

“Because my heart in anxious, thinking of the days to come. All my works are dear to me. Is it not enough that Melkor should have marred so many? Shall nothing that I have devised be free from the dominion of others?” They discussed it for a while until Manwë finally responded, “When the Children awake (the Dwarves), then the thought of Yavanna will awake also, and it will summon spirits from afar, and they will go among the kelvar (the fauna of Middle-earth) and the olvar (the flora of Middle-earth), and some will dwell therein, and be held in reverence, and their just anger shall be feared.”

This breath of spirits and life created two powerful and fascinating beings, The Great Eagles and the Ents. Yavanna was able to work with Manwë to build a defense system into her creations, thus bringing sentience to the Great Eagles (which you’ll remember from the end of The Lord of the Rings, when Gandalf speaks with them and gets them to assist in gathering up the Hobbits) and the Ents (Yay Treebeard!) as guardians, so that even if Melkor’s influence encroaches upon the Children (both first-born, Elves and Man, and Second Born, Dwarves) and they foster a desire to mar the land further than even Melkor was able to, these sentient beings would be there for protection.

We are finally getting a broader understanding of how the world came into being, but what transpired to bring the Children to wake into the world? Let’s find out next week as we unfurl “Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of The Beginning of Days

“Behind the walls of the Pelóri the Valar established their domain in that region which is called Valinor; and there were their houses, their gardens, and their towers. In that guarded land the Valar gathered great store of light and all the fairest things that were saved from the ruin; and many others yet fairer they made anew, and Valinor became more beautiful even than Middle-earth in the Spring of Arda; and it was blessed, for the Deathless dwelt there, and there naught faded nor withered, neither was there any stain upon flower or leaf in that land, nor any corruption or sickness in anything that lived; for the very stones and waters were hallowed.“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we begin our pathway into the Quenta Silmarillion and learn of the beginning of the First Age, while getting some very useful backstory into the elves and man.

In the past few weeks we were introduced to the Valar and their predilections and abilities, which is imperative back story as we jump into the Silmarillion.

The story starts with mention of the First War, and if you remember, we don’t really know anything about it, because we’re getting everything from the Eldar, and the First War was before they came into their own in Arda. What we do know is that Melkor fought the Valar for control of the land, until Tulkas the Strong came down and “Melkor fled before his wrath and his laughter.“

With Melkor gone, at least temporarily, the Valar began to build Arda bringing “order to the seas and the lands and the mountains.” Once Yavanna planted seeds, the Valar realized they needed light to help life flourish, so Aulë “wrought two mighty lamps for the lighting of Middle-earth… One lamp they raised near the north of Middle-earth, and it was named Illuin; and the other was raised in the south, and it was named Ormal.”

The land flourished with the Valar and the light of the lamps, but Melkor had spies among the Maiar, “and because of the light of Illuin they did not perceive the shadow in the north that was cast from afar by Melkor.”

Because they didn’t notice Melkor, he came south and “began the delving and building of a vast fortress, deep under the Earth, beneath dark mountains… That stronghold was named Utumno.” His corruption spread from Utumno “and the Spring of Arda was marred.”

Another war broke out and Melkor “assailed the lights of Illuin and Ormal, and cast down their pillars and broke their lamps.” causing “destroying flame (which was) poured out over Earth,” scarring the land. The Valar were able to stop Melkor after this, but it was too late and “Thus ended the Spring of Arda.“

The Valar decided that there was no appropriate place to live, “Therefore they departed from Middle-earth and went to the land of Aman,” and to protect this land “they raised the Pelóri, the Mountains of Aman, highest upon Earth.” Upon the highest mountain Manwë (the Lord of Air and Winds) build his throne. “Taniquetil the Elves name that holy mountain.” Then we get the quote which opens this essay, and we understand that this land of Aman, had now become Valinor.

It was then, once they made their home in Valinor that Yavanna helped grow (through her song) the “Two Trees of Valinor;” Telperion and Laurelin. Telperion bloomed for six hours then stopped, then Laurelin bloomed for another six hours: “And each day of the Valar in Aman contained twelve hours, and ended with the second mingling of the lights, in which Laurelin was waning and Telperion was waxing.” It was a time of great joy for the Valar, to be free of Melkor and to continue to develop Valninor:

“Thus began the Days of the Bliss of Valinor; and thus began also the count of time.”

What significant about this is the aspect of time. The age of the Children of Ilùvatar was coming and the instance of time was it’s catalyst. The Elves are immortal, they “die not till the world dies, unless they are slain or waste in grief.” But men are mortal and they need to have a concept of time to understand what their life capability is. We’ll see more of this later in the essay.