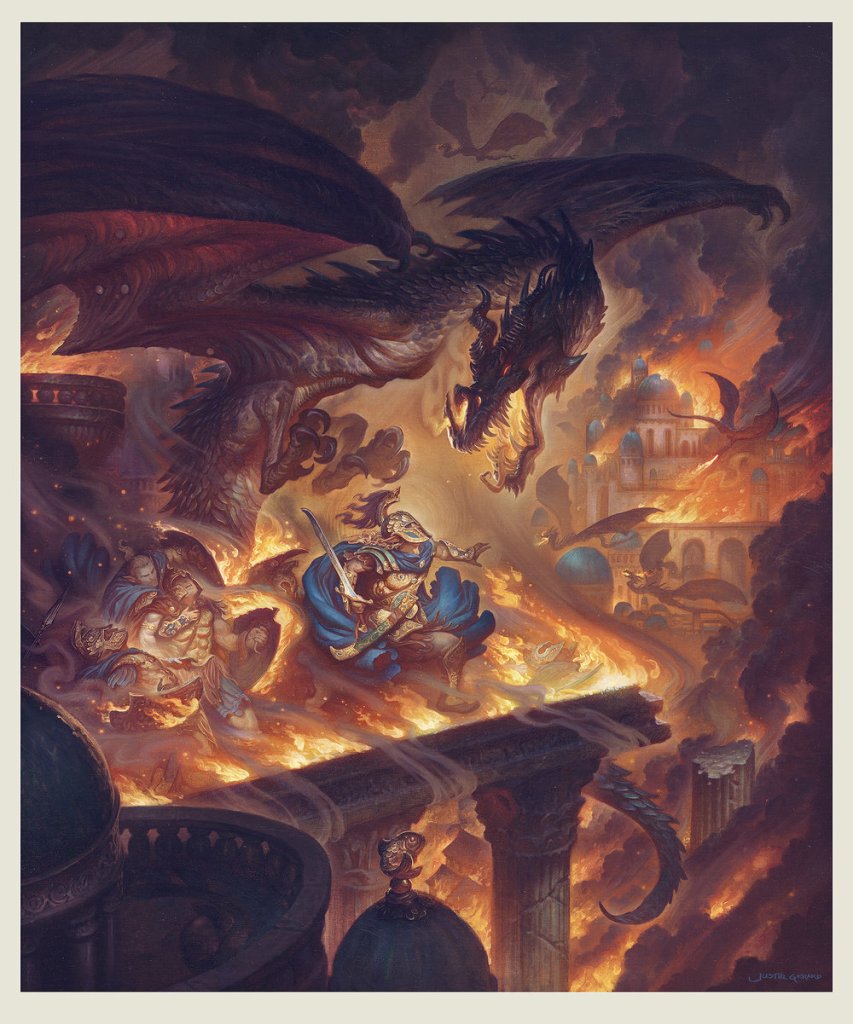

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2; Túrin’s last tragedy

“There did she stay her feet and standing spake as to herself: ‘O waters of the forest whither do ye go? Wilt thou take Nienóri, Nienóri daughter of Úrin, child of woe? O ye white foams, would that ye might lave me clean – but deep, deep must be the waters that would wash my memory of this nameless curse. O bear me hence, far far away, where are the waters of the unremembering sea. O waters of the forest wither do ye go?’ Then ceasing suddenly she cast herself over the fall’s brink, and perished where it foams about the rocks below; but at that moment the sun arose above the trees and light fell upon the waters, and the waters roared unheeding above the death of Nienóri (pg 109-110).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we conclude the tale of Turambar and the Foalókë and experience the last tragedies of Turambar’s life.

We left off last week with Turambar and Níniel deciding to ride out against the Foalókë, Glorund, to kill the drake. They gathered with them a group of men desperate to rid their land of the terrible beast, but on the way to the drake, they slowly abandoned the mission, leaving only a handful of mercenaries left, and “Of these several were overcome by the noxious breath of the beast and after were slain (pg 104).”

Eventually, only Turambar and Níniel were left to face the beast. “Then in his wrath Turambar would have turned his sword against them, but they fled, and so was it that alone he scaled the wall until he came close beneath the dragon’s body, and he reeled by reason of the heat and of the stench and clung to a stout bush.

“Then abiding until a very vital and unfended spot was within stroke, he heaved up Gurtholfin his black sword and stabbed with all his strength above his head, and that magic blade of the Rodothlim went into the vitals of the dragon even to the hilt, and the yell of his death-pain rent the woods and all that heard it were aghast (pg 107).”

The death of Glorund would seem like a cause for celebration, but unfortunately, Turambar’s efforts to end the scourge of the great worm only ended up in more tragedy.

His death was foretold from his early mistakes, and if he had only taken a little more time and been less impetuous, his life wouldn’t have ended up the way it was. Turambar is an echo of Hotspur, the firey prince of Shakespeare’s histories, where he has everything going for him, but because of his temper and strong desires, his life is degraded.

So how could Turambar’s life degrade from killing the drake, you might ask? Well, he passes out next to the Foalókë, and when Níniel comes to find him, she thinks he died along with the dragon in mortal combat. She weeps next to Turambar. She weeps for her husband. She cries for the man who killed the dragon and saved their people. But her weeping wakes Glorund for one last gasp.

“But lo! at those words the drake stirred his last, and turning his baleful eyes upon her ere he shut them for ever said: ‘O thou Nienóri daughter of Mavwin, I give thee joy that thou has found thy brother at last, for the search hath been weary – and now is he become a very mighty fellow and a stabber of his foes unseen (pg 109).”

Glorund died with these words, but what fell with the great beast was the glamor he held over Nienóri. She was suddenly aware of who she was and who Túrin was. Realization bombarded her that she had been married to her brother and had children with him. Aghast at the knowledge, she heads off to a waterfall called the Silver Bowl, contemplative. But instead of Nienóri coming to terms with the events of the last number of years, she is overwhelmed, and we get the quote that opens this essay.

Túrin wakes and quickly realizes that she is gone. He heads back to the village where the people already know the secret of their king and queen, and Túrin pulls it out of them. This being Túrin and his tragic story, he responds how you would expect him to:

“So did he leave the folk behind and drive heedless through the woods calling ever the name Níniel, till the woods rang most dismally with that word, and his going led him by circuitous ways ever to the glade of Silver Bowl, and none had dared to follow him (pg 111).”

Túrin turns to his sentient sword and begs for the only absolution his troubled life could understand.

“‘Hail Gurtholfin, wand of death, for thou art all men’s bane and all men’s lives fain wouldst thou drink, knowing no lord or faith save the hand that wields thee if it be strong. Thee I only have now – slay me therefore and be swift, for life is a curse, and all my days are creeping foul, and all my deeds are vile, and all I love is dead (pg 112).'”

“and Turambar cast himself upon the point of Gurtholfin, and the dark blade took his life (pg 112).”

The tale doesn’t end here, however; Tolkien switches us back to Mavwin and her search for her children. She wept and went into the woods, and the region of Silver Bowl became haunted by their past and presence.

Tolkien also lays on some of his Christianity, which is notably absent in the later editions:

“Yet it is said that when he was dead his shade fared into the woods seeking Mavwin, and long those twain haunted the woods about the fall of Silver Bowl bewailing their children. But the Elves of Kôr have told, and they know, that at last Úrin and Mavwin fared to Mandos, and Nienóri was not there nor Túrin thier son (pg 115).”

Both the children ended up as spirits because their transgressions forbade them from the afterlife.

Join me next week as we dive more into the religion of the story and break down just what Tolkien was going for with such a horrifically tragic story.

Magic Does Exist

It’s easy to write the phrase “with everything going on in the world.” There is, and will always be, a never-ending stream of horrible things happening, so perspective is more critical now than ever.

We live in a digital age, where news and op-eds are at our fingertips 24/7, and things like social media have fostered an interesting change to our psyche. We have created perspective silos, where we only see what we want to see, creating division between one another. Then we have politicians who are only out for themselves who are stoking this division.

These kinds of rifts have and will always be around, but one thing we have forgotten as a society, as humans, and as creative beings is that there is still magic in the world; and magic is what will save us from ourselves.

I was driving with my wife this past weekend on the central coast of California celebrating our tenth anniversary, and off the coast, oil rigs were sitting out in the ocean. I had no idea they were there (or that there was a drilling operation so close to our coast), so naturally, being a fantasist, I immediately thought they were some ship. My mind turned to Pirates out in the ocean, sailing the wide blue expanse in search of meaning and freedom and booty.

Of course, I didn’t verbalize this and asked what they were because I couldn’t get the visual out of my head (Though my wife is awesome and knew exactly what I was thinking and why I asked). When she told me what they were, I nodded, and we moved on, but there was magic in the world again for that brief moment. There was still the possibility of a real-life version of the Pirates of the Caribbean, where there were curses and magic and epic fights on the seven seas, where no one really dies, and you always find out that there is just one more item beyond reach that can give understanding and have the world make sense.

People, in this digital age, have forgotten that there is magic in the world. The drive to get clicks, and the pressure to be famous or influence and show how good your life is to strangers online has taken precedence over enjoying the little things.

Speaking of pirates, The Pirates of the Caribbean series was so popular (and Disney in general) because it introduced the world’s elements that were thought impossible.

On the one hand, you have the East India Company, which represents reality, corporations, and the everyday grind. Everything about that concept is about control and making the world smaller. About controlling the magic in the world for profit. The more we know about the world, the less magic there is, the less there is to wonder about, and we end up just accepting that the daily grind is all there is, and the company gets what it wants… good workers that realize there is nothing beyond their Friday paycheck.

Captain Jack introduces us to a character who knows there is magic left in the world. But not magic in the traditional sense. Not witches, wizards, and spells (though that can be a part of it), but wonder and imagination. We are asking people to grow up far too quickly, telling them that the harsh reality is all there is, and disparaging people who want to believe there is something more in the world. We tell people to “grow up,” stop being childish and take things more seriously.

But what does that do for you? If all you can do is internalize the cold, hard reality, it only leaves room for disdain, hatred, and sadness. Then disassociation is the only thing left, which isn’t a healthy alternative.

Fantasy isn’t necessarily escapism but a filter on the lens of the world. Fantasy allows you to experience the world in a way where magic still exists.

There is a reason that Disneyland is “the happiest place on earth,” and it’s because they focus on the individual details. They miss no brush stroke; every rock is overturned. There are hidden Mickeys throughout the park. Each land can let you immerse yourself in the wonder of that world. The details allow you to experience the magic that still exists in our world, so your mind can slip into that magic when you hear a song or see an article of clothing.

Magic and fantasy are not about escapism but realizing that the world isn’t myopic. Life isn’t dictated by corporations or political rhetoric. Life is created and run by magic, and things are still hidden. Look hard enough to find your hidden mickey in the sand, trees, or oceans. Be your own Imagineer and make your own mystery, create your own wonder. Discover your own treasure map that leads to some hidden fantasy, even if you can never find it.

Magic is still alive and well in the world, and we are here to experience it. Work will always be there; go and find your magic. Go and find your purpose.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Turambar

“Now coming before that king they were received well for the memory of Úrin the Steadfast, and when also the king heard of the bond tween Úrin and Beren the One-handed and the plight of that lady Mavwin his heart became softened and he granted her desire, nor would he send Túrin away, but rather said he: ‘Son of Úrin, thou shalt dwell sweetly in my woodland court, nor even so as a retainer, but behold as a second child of mine shalt thou be, and all the wisdoms of Gwendheling and of myself shalt thou be taught (Pg 73).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we introduce Túrin and his tragedy while getting some commentary about Tolkien’s decision to create a story throughline instead of the history that the tale became.

Christopher begins this chapter by speaking of the timeframe of the writing itself and how his father wrote Turambar in the time between the original script of Tinúviel and the edits of that tale:

“There is also the fact that the rewritten Tinúviel was followed, at the same time of composition, by the first form of the ‘interlude’ in which Gilfanon appears, whereas at the beginning of Turambar there is reference to Ailios (who was replaced by Gilfanon) concluding the previous tale (pg 69).”

I bring this to your attention because of the profound changes Tolkien was making at the time and the apparent fact that Christopher missed when he made the assertion of Beren always being intended to be Eldar.

Ailios or Gilfanon said, shortly after his introduction, “‘Now all folk gathered here know that this is the story of Turambar and the Foalókë, and it is,’ said he, ‘a favourite tale among Men, and tells of very ancient days of that folk before the Battle of Tasarinan when first Men entered the dark vales of Hisilómë (pg 70).'”

Tolkien establishes almost immediately that this is a story about Men, not Gnomes or Elves, and it is only a few pages later that we get this passage:

“…but the deeds of Beren of the One Hand in the halls of Tinwelint were remembered still in Dor Lómin, wherefore it came into the heart of Mavwin, for lack of other council, to send Túrin her son to the court of Tinwelint, begging him to foster this orphan for the memory of Úrin and of Beren son of Egnor (pg 72).”

Here, we get a direct correlation between Beren and Úrin, one of which is a Man and the other is an Elf in the established setting. To go even further, in the opening quote of this essay, Tolkien states that Beren and Egnor were friends, and before this passage, in early Tolkien, there was no love lost between Elves and Men. This is the first instance of the earlier works where an Elf and a Man were friends.

I contend that this was an accident on Tolkien’s part because he was already beginning to think of Beren and Egnor as Men. After all, it fits the story so much better. There is even a passage where Egnor is “akin to Mavwin.” Egnor is Beren’s father, and Mavwin is Túrin’s mother, thereby stating that Egnor was, at the very minimum, a half-elf, but such things never existed in Tolkien. (You might remember Elros and Elrond, who were born half-elves; however, the Vala made them decide which side they were to fall on, and Elros became a man and founded the Númenóreans and Elrond became an Elf…and we know how that story ends)

Tolkien also brings back the Path of Dreams, or Olórë Mallë, to explain how Ailios (Gilfanon) knows these stories firsthand (there is a reference that he also knows the story of the fall of Gondolin: “and I knew it long ere I trod Olórë Mallë in the days before the fall of Gondolin (pg 70).” The more that I read of these Lost Tales, the more I understand why Tolkien took Gilfanon out of the story, and why he also took out the transitions.

Tolkien initially wanted these stories to flow into one another with a central story hub (think Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man) because he was worried that people would not be interested in the dry history of a land that didn’t exist. To tell this tale in a “Hobbit” style might make it more accessible to the everyday reader. However, he ran into the problem of how to make it work. He knew who Eriol was, and there were plans for him (which I believe will come to light in the last chapter of The Book of Lost Tales, part 2), but how does he get the surrounding characters into the work? The people who tell the tale? Well, he created things like Olórë Mallë, a sleep bridge that can get men (and only men apparently, as no Elves needed it because of their immortality) to different areas of space and time. He also created spaceships (literally ships that could sail across the sky) but decided to limit that to elevate a single character, Eärendil, to a godlike being as he sails his ship Vingilot across the sky.

These ideas were a means to an end, and he only used them to tell the story. He eventually realized that these plot devices were only taking away from the story instead of enhancing it, but his quandary was that to take them away removes all credence of the story that was being told. For this reason, I believe Tolkien took out the transition pieces with Eriol learning the histories.

That leads us right into Turambar because, as Ailios describes Úrin and how he knew Beren and his travails. Mavwin, Túrin’s mother and Úrin’s wife, decided that Túrin would be safer staying with Tinwelint, than he would up north with the threat of Melko.

Thus, Túrin’s story begins.

“Very much joy had he in that sojourn, yet did the sorrow of his sundering from Mavwin fall never quite away from him; great waxed his strength of body and the stoutness of his feats got him praise wheresoever Tinwelint was held as lord, yet he was a silent boy and often gloomy, and he got not love easily and fortune did not follow him, for few things that he desired greatly came to him and many things at which he laboured went awry (pg 74).”

Join me next week as we continue the tragedy of Túrin Turambar!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Tale of Tinúviel, commentary

“In the old story, Tinúviel had no meetings with Beren before the day when he boldly accosted her at last, and it was at that very time that she led him to Tinwelint’s cave; they were not lovers, Tinúviel knew nothing of Beren bu that he was enamoured of her dancing, and it seems that she brought him before her father as a matter of courtesy, the natural thing to do (pg 52).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we’ll briefly cover Christopher’s commentary on The Tale Of Tinúviel and give some final thoughts on the story.

Much of what Christopher covers (Christopher is J.R.R. Tolkien’s son and editor. This book is posthumously published, and Christopher both compiled it and edited it) in his lengthy comments following the Tale of Tinúviel are the same or very similar to everything that I have covered in the previous Blind Reads, so we’ll speak about the most critical insights and give some context.

Before we jump into that, however, Christopher included a second draft (or at least pieces) of The Tale of Tinúviel just after the first edition and before his comments.

“This follows the manuscript version closely or very closely on the whole, and in no way alters the style or air of the former; it is, therefore, unnecessary to give this second version in extenso (pg 41).”

The most significant change that I noticed was the nomenclature. The forest’s name changed to Doriath, and the names Melian and Thingol are introduced here for the first time.

We also have the adjustment of Beren’s father from Egnor to Barahir and Angamandi to Angband. Most importantly, we first mention Melko as Morgoth (The Sindarin word for Melkor).

This last adjustment may seem like an alteration of monikers to streamline the narrative; however, knowing how The Silmarillion was published and the extensive lists of names, not to mention the number of names in each language many of the characters had, we know he did this intentionally.

Many people assume (and rightly so because the theory has become so ubiquitous) that Tolkien built a language (Elvish) and then developed a story and world based on that language. This theory makes a certain amount of sense because he was a linguist. Still, read these books (or, more importantly, Christopher’s annotation). You’ll understand that the world-building and the language came conjointly because of Tolkien’s desire to tell a fairy tale that would become England’s own. It was all supposed to start with this first story: The Tale of Tinúviel.

The names evolved because Tolkien was developing his language and the world the story took place in, and the names he originally used no longer made sense.

A prime example of this is in the second version of the story, “Beren addresses Melko as ‘most mighty Belcha Morgoth (pg 67).'” I’ll let Christopher explain:

“In the Gnomish dictionary Belcha is given as the Gnomish form corresponding to Melko, but Morgoth is not found in it: indeed this is the first and only appearance of the name in the Lost Tales. The element goth is given in the Gnomish dictionary with the meaning ‘war, strife’; but if Morgoth meant at this period ‘Black Strife’ it is perhaps strange that Beren should use it in flattering speech. A name-list made in the 1930s explains Morgoth as ‘formed from his Orc-name Goth ‘Lord of Master’ with mor ‘dark or black’ prefixed, but it seems very doubtful that this etymology is valid for the earlier period (pg 67).”

Tolkien was evolving and creating new languages for the Eldar and the Orcs, Dwarves, and Valar. Beyond that, he was developing dialects within these languages, so a Sindarin name would be different from a Noldoli name, which is where many people get confused about the number of names in The Silmarillion and how the rumor got started that Tolkien created the languages first and the world second. The above quote is the irrefutable proof (not to mention the extensive changes to The Lost Tales).

We can see the linguistic changes Tolkien is making, which in turn changes the story’s core, but there is some very interesting world-building that Tolkien has done in the augments between drafts.

The first example surrounds the Simarils; “The Silmarils are indeed famous, and they have a holy power, but the fate of the world is not bound up with them (pg 53).”

Tolkien understood the Maguffin (a plot device that sets the characters into motion and drives the story) early on. Still, his original intention was to tell the tale of two lovers, he and Edith, but in the names of Beren and Lúthien (Tinúviel). What he came to realize as he went through drafts and started to build the history of the world (this second version was also the first mention of Turgon the King of Gondolin because Tolkien had begun working on the story The Fall of Gondolin before he went back to the second draft of the Tale of Tinúviel), was that there needed to be a through line to bring the different tales together into one single history, rather than having a bunch of disparate short stories spattered throughout history. The Silmarils became that Maguffin. They grew in mystery and power in his mind. The tale of Valinor became the precursor and introduction to the power that the Silmarils contained so that they might tell a much larger story and have the whole of the world seeking the power they held (much like the One Ring in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings).

The Tale of Tinúviel is a fascinating addition to the Legendarium, but it does feel a little one-note beside its later counterpart, Of Beren and Lúthien. What is most interesting is the fairy tale manner in which Tolkien tells the tale. The first big bad we see is a cat who captures our hero and makes him hunt for them because they’re lazy cats. This anthropomorphized creature is a common theme in fairy tales, and Tevildo never truly poses a real threat, especially when Huan the Hound shows up. Then, when Tinwelint imprisons Tinúviel in a tall tower to keep her from going after her love, we get impressions of all the old Anderson Fairy Tales. In this early version, it is apparent that Tolkien was going for a fairy tale vibe (which in fact was his original intention before realizing that he wanted to make it more realistic, more gritty), but instead of eventually disneyfying it, he went deeper and darker and turned the tale into something bold and breathtaking, and seeing the transformation is something to behold.

We’ll take a week off before returning to the next story, “Turambar and the Foalókë.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Tale of Tinúviel, conclusion

“Lo, the king had been distraught with grief and had relaxed his ancient wariness and cunning; indeed his warriors had been sent hither and thither deep into the unwholesome woods searching for that maiden, and many had been slain or lost for ever, and war there was with Melko’s servants about all their northern and eastern borders, so that the folk feared mightily lest that Ainu upraise his strength and come utterly to crush them and Gwendeling’s magic have not the strength to withold the numbers of the Orcs (pg 36).”

Welcome back to another Blind read! This week, we finish The Tale of Lúthien and reveal more differences between The Book of Lost Tales and The Silmarillion.

We left off last week with Lúthien and Huan saving Beren from Tevildo and the cats. After escaping, they retreated and recovered, but there was still that everlasting desire to go and get the Silmaril back, so they devised a plan.

“Now doth Tinúviel put forth her skill and fairy-magic, and she sews Beren into this fell and makes him to the likeness of a great cat, and teaches him how to sit and sprawl, to step and bound and trot in the semblance of a cat… (pg 31).”

They go to Angamandi and the court of Melko, where they come into contact with Karkaras (an early version of Carcharoth), who was suspicious of Lúthien, but her disguise on Beren held. Lúthien played her magic on the great wolf and put him to sleep “until he was fast in dreams of great chases in the woods of Hisilómë when he was but a whelp… (pg 31).”

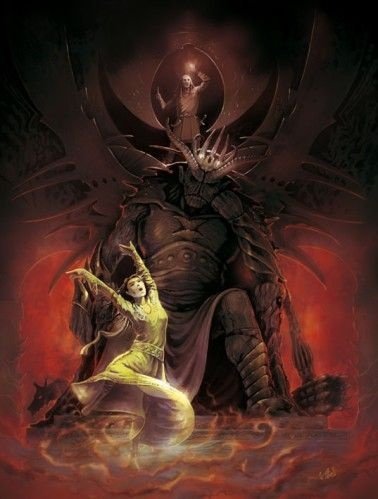

Both Lúthien and Beren make their way to Melko’s throne room, filled with cats and creatures, and Beren blended in with them, and took up a “sleeping” position underneath Melko’s throne. Lúthien on the other hand stood with pride before the Ainu, “Then did Tinúviel begin such a dance as neither she nor any other sprite or fay or elf danced ever before or has done since, and after a while even Melko’s gaze was held in wonder (pg 32).”

Everyone in the chamber, all the cats, thralls, Fay, and even Beren, fell asleep while listening to Tinúviel’s Nightingale voice. Her movements were just as hypnotizing, “and Ainu Melko for all his power and majesty succumbed to the magic of that Elf-maid, and indeed even the eyelids of Lórien had grown heavy had he been there to see (pg 33).”

Tinúviel woke Beren, careful to let everyone else continue to sleep. “Now does he draw that knife that he had from Tevildo’s kitchens and he seizes the mighty iron crown, but Tinúviel could not move it and scarcely might the thews of Beren avail to turn it (pg 33).”

They eventually pry one Silmaril off the crown, but Beren goes for a second one in his greed, only to break his blade and wake Melkor. Tinúviel and Beren fled Angamandi, pursued by Karkaras, the Great Wolf. They battled, and Karakaras bit off Beren’s hand bearing the Silmaril.

But, “being fashioned with spells of the Gods and Gnomes before evil came there; and it doth not tolerate the touch of evil flesh or of unholy hand (pg 34).” So Karkaras began to be burned alive from the inside out and screamed for all he had. The screams of the Great Wolf woke the castle, and Beren and Tinúviel fled for their lives.

They ran with an entire Orc army of Melko on their trail and had many encounters with them but eventually “stepped within the circle of Gwendeling’s magic that hid the paths from evil things and kept harm from the regions of the woodelves (pg 35).” Otherwise known as the Girdle of Melian.

They make their way to the king, and we get the quote that opens this essay, but Tinwelint saw no Silmaril, so they related the tale, and Beren stood before the king and said, “‘Nay, O King, I hold to my word and thine, and I will get thee that Silmaril or ever I dwell in peace in thy halls (pg 38).'”

So Beren went back out into the wilds to find the body of Karkaras and claim the Silmaril, but he didn’t go alone. “King Tinwelint himself led that chase, and Beren was beside him, and Mablung the heavy-handed, chief of the king’s thanes, leaped up and grasped a spear (pg 38).”

They eventually came upon a vast army of wolves, and among them was Karkaras, still alive but howling in agony. There was a great battle, “Then Beren thrust swiftly upward with a spear into his (Karkaras) throat, and Huan lept again and had him by a hind leg, and Karkaras fell as a stone, for at that same moment the king’s spear found his heart, and his evil spirit gushed forth and sped howling faintly as it fared over the dark hills to Mandos; but Beren lay under him crushed beneath his weight (pg 39).”

Beren was mortally wounded beneath Karkaras, and they tried to nurse him back to health. In the meantime, Tinwelint and Mablung found the Silmaril in Karkaras’ body. Tinwelint refused to take it unless Beren gave it to him to honor the fallen warrior, so Mablung grabbed the Silmaril and handed it to Beren, who, with his dying breath, said, “‘Behold, O King, I give thee the wondrous jewel thou didst desire, and it is but a little thing found by the wayside, for once methinks thou hadst one beyond thought more beautiful, and she is now mine (pg 40).'”

The tale ends with Beren dying, and we get a short interlude of Vëannë telling Eriol that there were many other tales of Beren coming back to life but that the only one she thought was true was the tale of the Nauglafring, otherwise known as the Necklace of the Dwarves.

The tale’s bones are the same all the way through, with some very significant character changes, like the addition of Celegorm and Curufin and the subtraction of Tevildo. Still, quite honestly, these things are entirely necessary because, on its own, this is just a tragic tale. When you add the other elements, the world expands, and the characters gain more agency. Suddenly, Beren’s quest affects far more than just the players in the story, and we get a much broader realization of what Beleriand is, was, and will become.

Join me next week for a short second edition of this tale, some commentary, and some final thoughts!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2; The Tale of Tinúviel, cont.

“Now all this that Tinúviel spake was a great lie in whose devising Huan had guided her, and maidens of the Eldar are not wont to fashion lies; yet have I never heard that any of the Eldar blamed her therein nor beren afterward, and neither do I, for Tevildo was an evil cat and Melko the wickedest of all beings, and Tinúviel was in dire peril at their hands (pg 27).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! We left off last week with Beren getting captured by Tevildo, Prince of Cats, and Lúthien escaping the tower her father imprisoned her in to go and find and free Beren from his thralldom.

Before the story, let’s review what happened in The Silmarillion.

Lúthien escaped from Doriath and chased after Beren, but where there are cats in The Book of Lost Tales, The Silmarillion had Wolves. Beren was captured by Sauron, the Master of Wolves (many of his minions in this story were werewolves, and he even commanded the Wolf King Carcharoth), and on her way to find him, Lúthien meets up with Huan, the Hound of Valinor.

Huan takes Lúthien to his masters, Celegorm and Curufin, who were Fëanor’s sons (Eldar who swore to get the Silmarils back at the cost of all else). The Book of Lost Tales is a significant departure from the older story because these two brothers played a nefarious role in the remaining history of Beleriand. They caused strife and trouble for our heroes many times and generally stood in the way only because of their oath, and they never appear in the earlier version.

This deception is the first instance of their devious natures. They instructed Huan to bring Lúthien before them and once there, Celegorm devised a plan to marry her because of her beauty, but more importantly because of her lineage. Celegorm was seeking power, plain and simple. He tricks Lúthien, brings her to Nargothrond, and imprisons her until his plan can be complete.

Here, Huan felt pity for Lúthien, who only wanted to save her love, and felt disgust for his master. Huan frees Lúthien, leading her to Angband to confront Sauron and free Beren.

When they get there, Sauron sends his werewolves out to kill them, but Huan kills them one by one. Sauron then shapeshifts and changes himself into a werewolf (doubtless being one of those quintessential bad guys who say, “If you want something done right, you gotta do it yourself.”), and heads out to meet them. There is a pitched battle, with Sauron changing into different shapes and trying other tactics. Still, eventually, Huan defeats him, and Sauron flees in the form of a Vampire after leaving the keys to the prisons for Huan and Lúthien to take.

This fight shows the absolute power of Huan. Sauron gained strength and influence over the remaining years of his life, but the fact that Huan and Lúthien were able to best him in battle when, later on, it took armies to stand up to him is a testament to Huan’s strength and Lúthien’s ingenuity.

They freed Beren and fled Angband, only to come across our favorite dastardly Eldar, Celegorm, and Curufin. They battled, and Beren won, deepening their shame and anger. Not only were the great sons of Fëanor defeated, but a human bested them to boot!

Beren then snuck back to Angband after both Huan and Lúthien slept, determined to get the Simaril and prove his worthiness, but when they woke and found him gone, they disguised themselves as a vampire and werewolf and went after him. They got to Morgoth’s chambers, and Lúthien used her magic to put everyone to sleep and Beren cut a Silmaril from Morgoth’s crown before escaping from the stronghold.

As they exited, Carcharoth, the King of Wolves jumped out and attacked them, biting off Beren’s hand that held the Silmaril and thus halting their quest. Huan summoned The Eagles of Manwë (you might remember these majestic creatures from the end of The Return of the King when they rescued Frodo and Sam from Mount Doom), and they escaped from Angband.

In The Book of Lost Tales, Sauron is not present. Instead, it’s Tevildo who has Beren captured. Lúthien still meets up with Huan, but we have a sort of natural cat-and-dog relationship there:

“None however did Tevildo fear, for he was as strong as any among them, and more agile and more swift save only than Huan Captain of Dogs. So swift was Huan that on a time he had tasted the fur of Tevildo, and though Tevildo had paid him for that with a gash from his great claws, yet was the pride of the Price of Cats unappeased and he lusted to do a great harm to Huan of the Dogs (pg 21).”

Tinúviel travels with Huan to Angamandi (the early version of Angband) and finds a resting cat sentry just before its gates. Tinúviel asks to speak with Tevildo and plays to the guard’s pride to get her in to gain an audience.

When she is brought before Tevildo, she asks to speak with him privately, but he is not humored:

“‘Nay, get thee gone,’ said Tevildo, ‘thou smellest of dog, and what news of good came ever to a cat from a fairy that had dealings with dogs (pg 24)?”

Tinúviel sweet-talks her way in and spies Beren in the kitchen doing his thrall duties. She speaks loudly, letting Beren know that she’s there, and then we get the opening quote of this essay, where she divulges Huan’s plan: Huan is hurt and helpless just outside in the forest, the cats must kill him!

“Now the story of Huan and his helplessness so pleased him (Tevildo) that he was fain to believe it true, and determined at least to test it; yet at first he feigned indifference (pg 27).”

Tevildo and a small group of Cats went out to try and end Huan, only to fall into the trap. Huan killed all but Tevildo, who barely escaped and lost his golden collar before fleeing up a tree.

Tinúviel took the golden collar and brought it before Tevildo’s court and got all of his prisoners released, along with a curiously named Gnome.

“Lo, let all those of the folk of the Elves or of the children of Men that are bound within these halls be brought forth,’ and behold, Beren was brought forth, but of other thralls there were none, save only Gimli, an aged Gnome, bent in thraldom and grown blind, but whose hearing was the keenest that has been in the world, as all songs say (pg 29).”

This name was undoubtedly used again once the languages were fleshed out and Tolkien realized that Gimli was much more of a dwarven name than an Elvish name, but he doesn’t appear again in this story (that I’ve read so far), so I think it was just a name Tolkien loved.

Lúthien, Beren, and Huan escaped, and the cats were ashamed. Morgoth’s anger was so great that they lost face, and the power of the cats was never the same from then on.

We’re getting close to the end! Join me as we cover the first written ending to The Tale of Tinúviel next week!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Lineage of Tinúviel

“Lo now I will tell you the things that happened in the halls of Tinwelint after the arising of the Sun indeed but long ere the unforgotten Battle of Unnumbered Tears. And Melko had not completed his designs nor had he unveiled his full might and cruelty (pg 10).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we begin Tolkien’s premier work in earnest and dissect the differences between what is in The Book of Lost Tales and what would eventually come in The Silmarillion.

The opening quote of this essay introduces the story to the reader, setting the stage for the events to come, but then Tolkien takes a step back and talks of the Elves of Doriath (which were not called such in this early version).

“Two children had Tinwelint then, Dairon and Tinúviel, and Tinúviel was a maiden, and the most beautiful of all the maidens of the hidden Elves, and indeed few have been so fair, for her mother was a fay, a daughter of the Gods; but Dairon was then a boy strong and merry, and above all things he delighted to play upon a pipe of reeds or other woodland instruments, and he is named now among the three most magic players of the Elves… (pg 10).”

If you have read The Silmarillion, you will probably recognize Tinúviel, and also Dairon as close to a character who stuck around. Still, otherwise, the names of the rest of the characters are entirely different.

Starting with our Titular character, Tinúviel, we know she kept that name in The Silmarillion. It’s the name Beren gave her because it means Nightingale, and he called her that when he found her dancing and singing in the forest. Her name changed to Lúthien, but there is still enough of a thread that it’s easy to keep everything in order.

Next, we have Tinwelint, who gained many names in the future as Tolkien began to develop his languages. Tinwelint became Elwë Singollo, leader of the hosts of the Teleri Elves, along with his brother Olwë. When Elwë led his people from Cuiviénen to Beleriand (the Teleri were known as the Last-comers, or the Hindmost, because, well, they were the last to come to Beleriand of the Eldar), he settled in the forests of Doriath (Where Beren saw Lúthien dancing). He ruled there under his better-known name, Elu Thingol.

Gwendeling, his wife, was not mentioned in the above quote but was also known as Wendelin in the Book of Lost Tales. She is a fay who falls in love with Tinwelint, marries him, and has two children.

Gwendeling, in my opinion, is how Tolkien decided to make the shift for the Maiar because, through the development of the Lay of Lúthien, he understood that women should play a much more significant role than he had initially been written (probably because of the influence of Edith). Gwendeling needed to possess powers of influence, most notably creating the Girdle of Melian, a protective shield over Doriath.

Because of this more extensive influence, Tolkien changed her lineage, and she became a Maiar, along with all of the other “children of the Valar” or Fay who never had a specific history. Doing so enabled Tolkien to have the Maiar keep their power set while at the same time lessening the ability of the Valar to have children (because if they are immortal, what is to stop them from continuing to have children who could potentially mess with the timeline)?

So Gwendeling became Melian the Maiar but stayed wife to Eru Thingol. That enabled Tolkien to make Lúthien a more robust character because she is the daughter of a demi-god and an immortal, but it left him in a strange quandary. In the book of lost tales, Tinúviel had a brother Dairon, and if he were to remain, he would also have to be a little more potent than the other Eldar because of his mother’s blood.

Dairon in the Book of Lost Tales is very talented, but one of those kids without any drive, as we see from the quote above. What he did possess, however, was an uncanny ability for music. He was considered the third-best “magic player” in the land, behind Tinfang Warble and Ivárë. You might remember Tinfang Warble from The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, because he was the half-fay flutist in the Cottage of Lost Play.

To adjust this inequity of power, Tolkien decided to slightly change Dairon’s name to Daeron, who then became one of the greatest minstrels of all time; in fact, the only being to come close to him was Maglor, Fëanor’s son (who is probably the later iteration of Ivárë). However, he became just a regular Eldar, no longer Thingol and Melian’s son, but rather a trusted loremaster of Thingol. More importantly, he was deeply in love with Lúthien.

This adjustment makes for a slightly better tale because rather than her brother betraying her excursion after Beren, it is an unrequited lover looking out for her best interest when he betrays her trust and tells Thingol that she went after Beren.

That takes care of the family, but what then of Beren? The most provocative change that Tolkien made here is that in the Book of Lost Tales, part two, is that Beren is an elf, not a man.

I believe he did this for several reasons, but two of them stand out to me the most:

- Men were not awake yet. At the end of the Book of Lost Tales, part 1, we see that they are children lounging by the Waters of Awakening. Tolkien didn’t spend time developing them like in The Silmarillion. Plus, The Silmarillion is considered the history of the Elves, even though much more happens there, so it makes sense that Beren would be an elf early on.

- Changing Beren to a Man adjusts the Legendarium in a fun and dynamic way. Now we have the dichotomy of the difference between Elves and Men and what that would mean for them to come together, fall in love, and potentially have children. The remainder of the time in Middle-earth stems from this relationship, so Tolkien needed to adjust it.

That was a lot to break down in just the opening pages! Join me next week as we dive into the story proper!

Blind Read Through: J.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Link of Tinúviel

“Then there was eagerness alight, and Eriol told them of his wanderings about the western havens, of the comrades he made and the ports he knew, of how he was wrecked upon far western islands until at last upon one lonely one he came on an ancient sailor who gave him shelter, and over a fire within his lonely cabin told him strange tales of things beyond the Western Seas, of the Magic Isles and that most lonely one that lay beyond. Long ago had he once sighted it shining afar off, and after had he sought it many a day in vain (pg 5).“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we begin The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, with the story of Middle-earth, which was closest to Tolkien’s heart.

This story is the earliest written tale in the Legendarium, even earlier than the tales of Ilúvatar and the Valar. Tolkien wrote the first manuscript in 1917 amid the Great War, and I have to imagine that he did so because he wanted a release from the horrors of the war happening around him.

Tolkien wrote the Tale of Tinúviel about his wife, Edith Tolkien, and it is both a beautiful homage and the seed from which all Middle-earth blossoms.

Those who know the story of Beren and Lúthien realize it is the tale of a man who falls in love with the most beautiful elven maid alive. Not only is she beautiful and sings like a nightingale, but she is a strong woman, a warrior, and a leader. Tolkien has been very forthright with the fact that Lúthien is, in fact, Edith, and the story of Beren seeing Lúthien singing and dancing in the forest was a call back to their walks in the dense woods of England when they first met.

This also means that the world of Middle-earth that Tolkien built would not be possible without Edith. Everything that happens in the Legendarium stems from this first origin (though doubtless there are poems written before this story, this was the first instance Tolkien wrote a new world through the lens of prose instead of poetry). Lord of the Rings even stems from this story. It echoes in Aragorn and Arwen, the Third Age’s version of Beren and Lúthien. There is even a passage in The Lord of the Rings compares Aragorn and Arwen to Beren and Lúthien.

This love story was at the core of everything that Tolkien wrote, and he built the greater Legendarium to support the story of his love for his wife. Though the tale grew beyond this conception, it remains the core of everything in Middle-earth.

Reviewing this tale will take multiple weeks, so to kick it off, I’d like to start with Eriol’s story and the link between where we left off in The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Also with where this book begins with The Tale of Tinúviel.

The tome takes up days after the events of Book of Lost Tales, part 1, with Eriol wandering in Kortirion, learning Elvish language and lore. One day as he is talking with a young girl and in a role reversal, she asks him for a tale:

“‘What tale should I tell, O Vëanne?’ said he, and she, clambering upon his knee, said : ‘A tale of Men and of childrren in the Great Lands, or of thy home – and didst thou have a garden there such as we, where poppies grew and pansies like those that grow in my corner by the Arbour of the Thrushes?'”

It may seem strange to call out this quote, but I do so because the passage ends here. Tolkien must have had the idea that Eriol would tell the history of Men, whereas the people of the Cottage of Lost Play would tell the story of the early times and the Elves.

Christopher gives a few different iterations of this interaction. Still, in every one of them, the story gets taken out of Eriol’s mouth as Vëanne interrupts him and begins the Lay of Lúthien (I.E., The Tale of Tinúviel).

I wonder if the intent was for Eriol to have his section of the book (which never actually happened) because Tolkien spends time here to set it up:

“‘I lived there but a while, and not after I was grown to be a boy. My father came of a coastward folk, and the love of the sea that I had never seen was in my bones, and my father whetted my desire, for he told me tales that his father had told him before (pg 5.)'”

The opening quote in this section talks about his “wanderings.” Before we get into the Tale of Tinúviel proper, there is also Eriol’s unwitting interaction with a Vala:

“‘For knowest thou not, O Eriol, that that ancient mariner beside the lonely sea was none other than Ulmo’s self, who appeareth not seldom thus to those voyagers whom he loves – yet he who has spoken with Ulmo must have many a tale to tell that will not be stale in the ears even of those that dwell here in Kortirion (Pg 7).'”

Eriol, to me, is a fascinating character because he has such a history, and he’s a mariner. If Tolkien created some stories from Eriol’s perspective, we might be able to see Middle-earth from a slightly different perspective, that of a sea-faring folk.

We know that all the history had come before this discussion. All of the first age (The Silmarillion) and the Second age (Akallabeth), and even the Third Age (The Lord of the Rings) came before Eriol’s time. So we can think of this soft opening in Kortirion as a Fourth Age, where Men (read Humans) run the world, the Elves have retreated to hidden Valinor, and much of the pain from the Dark Lord has disappeared, or at very least forgotten, from the world.

Join me next week as we start The Tale of Tinúviel!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, Final Thoughts

“Melko shalt see that no theme can be played save it come in the end of Ilúvatar’s self, nor can any alter the music in Ilúvatar’s despite. He that attempts this finds himself in the end but aiding me in devising a thing of still greater grandeur and more complex wonder:–for lo! through Melko have terror as fire, and sorrow like dark waters, wrath like thunder, and evil as far from the light as the depths of the uttermost of the dark places, come into the design that I laid before you. Through him has pain and misery been made in the clash of overwhelming musics; and with confusion of sound have cruelty, and ravening, and darkness, loathly mire and all putrescence of thought or thing, foul mists and violent flame, cold without mercy, been born, and Death without hope. Yet is this through him and not by him; and he shall see, and ye all likewise, and even shall those beings, who must now dwell among his evil and endure through Melko misery and sorrow, terror and wickedness, declare in the end that it redoundeth only to my great glory, and doth but make the theme more worth the hearing, life more worth the living, and the World so much the more wonderful and marvellous, that of all the deeds of Ilúvatar it shall be called his mightiest and his loveliest.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we recap The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, and in doing so, speak about the more fantastic aspect of Middle-earth and Tolkien’s intention.

The Book of Lost Tales is an amalgam of Tolkien’s work throughout his life. Christopher has included some of his father’s earliest poems, scraps of notes stuck into notebooks, various illustrations, and books and books of re-writes to show the thought and care Tolkien put into the work.

John wanted to tell a fantastic story that would give people meaning. He wanted a new fairy tale that would anchor into our world and give people wonder and hope (and perhaps even give reasoning for things like The Great War).

Many critics have said that The Lord of the Rings is an allegory to Tolkien’s time in the war, and if you only read the book itself, it is easy to understand why. Tolkien, however, hated allegory and had often stated that he pulled inspiration from his time in the war, but there was no allegory there. That can be hard to swallow, especially when his fellow Inkling (a society of writers who met to critique and edit each other’s work), C.S. Lewis, thought allegory one of the greatest literary techniques.

The story produced in The Lord of the Rings was a work of love developed over many decades, but to create a work so deep and well established Tolkien wanted a robust history of the world, that history is what eventually became The Silmarillion.

But Tolkien, like many authors, wanted the history of the world to be a story in and of itself, so in the earlier iterations, we get the tale of Eriol, who in turn is told the story behind The Silmarillion.

The problem Tolkien ran into, however, was that history is difficult to tell in a story format. There are fantasies, records, and fairy tales told in the Silmarillion, but they come late in the book and feel more like what he would eventually write in The Lord of the Rings. The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, is Eriol learning instead about the Valar and how the Eldar (Gnomes in this earlier version) came into being. However, even in these earlier versions, we still need to catch minor differences with how Tolkien later decided to frame everything.

Facts, like the Maiar being the children of the Valar, the Eldar being Gnomes, and the sparse inclusion of Fëanor are stark differences to how the story eventually played out, and what is great about reading through this book was being able to read Christopher’s analysis (Tolkien’s son and editor) of where Tolkien tried to take the story, and where he decided to end up. This process is the magic of reading The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Part 2, I’m sure, will have just as many quirks, but part 2 is where the stories that built the history of Mankind came into being. Stories like the Lays of Lúthien, the Tale of Túrin Turambar, and the Fall of Gondolin all take place in the second half of these histories. These tales inform our characters in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Beyond The Silmarillion, there is minimal mention of the Valar or Ilúvatar.

In Christopher’s sentiment, the first book is less interesting because it’s about the development of the world itself and not necessarily about the people; thus, it’s harder to give stakes because we know what will eventually happen.

Knowing all this, Ilúvatar is the most provocative being or concept in Tolkien’s oeuvre. Ilúvatar is God for this World (even though the Valar intermittently are called gods, Tolkien later stripped them of that title for The Silmarillion).

The quote to start this essay is a perfect example of the fallibility of gods in general. Tolkien was deeply religious, and I’m sure he wrote Ilúvatar to be Middle-earth’s Yahweh and much of the struggle and philosophy in Middle-earth is how to accept or deal with the concept of Death. Death is a “gift” given to Man when they are born, so they might make life more meaningful. Death was not a concept until Morgoth sang its theme into existence.

This path makes Melkor the most tragic character in the pre-history of Middle-earth because, as we see from the opening quote, he has no choice. Ilúvatar, as the master creator, knew every theme he wanted to put into the world, and Death, hate, and suffering would be part of existence.

Iluvatar created each Vala to inform specific parts of his themes, but themes were all they were, meaning that the Valar had free will over what theme they were given. Iluvatar created Melkor to suffer. He created him to be a Dark Lord because he knew that without a Dark Lord making people work for their freedom, they would take their lives for granted.

Tolkien didn’t write Allegory; he wrote philosophy. Death is a gift because we cannot appreciate light without darkness. We cannot fully appreciate life without death.

Come join me next week as we begin our foray into “The Book of Lost Tales, part 2,” the second book of the Histories of Middle-earth!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1; The Hiding of Valinor, part 2

“Thereat did Tulkas laugh, saying that naught might come now to Valinor save only by the topmost airs, ‘and Melko hath no power there; neither have ye, O little ones of the Earth’. Nonetheless at Aulë’s bidding he fared with that Vala to the bitter places of the sorrow of the Gnomes, and Aulë with the mighty hammer of his forge smote that wall of jagged ice, and when it was cloven even to the chill waters Tulkas rent it asunder with his great hands and the seas roared in between, and the land of the Gods was sundered utterly from the realms of the Earth (pg 210).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we conclude the tale of The Hiding of Valinor, as Tolkien delves deep into how he wanted to create the world.

This week is a perfect example of what a plotter writer does to create their world. Speaking from my own experience, worldbuilding is one of the hardest things to do as a writer because you want to thread the needle between creating a full, lush, believable world and muddling that same world with incessant useless details.

The Book of Lost Tales was never an actual book but a collection of notebooks, poems, anecdotes, and loose scrap paper Tolkien used to create his world over decades. From The Great War’s trenches to The Hobbit’s eventual publication, he filtered these notes to make what would later become The Silmarillion.

The Book of Lost Tales holds all the different cockamamie concepts which could comprise a fairy world. Christopher tells us many times that some of the detail has been cut because the text was re-written so many times (potentially multiple times in pencil and erased until Tolkien had a version he liked enough to write it out in pen… which many times was still not the last iteration)

What I’d like to cover this week for some fun differences is the detail Tolkien went to explain how the world came into being, which he later cut because much of it has little or nothing to do with the actual world.

The first instance I’d like to cover is the minutia of the Sun and the Moon route.

The Valar have a council for multiple pages concerning how they would go about hiding Valinor: “Nonetheless Manwë ventured to speak once more to the Valar, albeit he uttered no word of Men, and he reminded them that in their labours for the concealment of their land they had let slip from thought the waywardness of the Sun and the Moon (pg 214).”

We’ve previously discussed the path the Sun and the Moon had taken because of where different Valar (and Ungoliant) took up their residence. Still, they worry about “removing those piercing beams more far, that all those hills and regions of their abode be not too bringht illumined, and that none might ever again espy them afar off (pg 214).”

Yavanna worried that the change in the movement of the light from either the Sun or the Moon could create strife in the world, so Ulmo told them they had nothing to worry about. The Ocean is so large that the Valar don’t even fully comprehend its magnitude, nor have they ever interacted with any of the creatures of the world, “but Vai runneth from the Wall of Things unto the Wall of Things withersoever you may fare…ye know not all wonders, and many secret things are there beneath the Earth’s dark keel, even where I have my mighty halls of Ulmonan, that ye have never dreamed on (pg 214).”

Ulmo tells the other Valar they have nothing to worry about because the world is so vast that Ilúvatar’s children could never find them after centuries of looking. To counteract that worry, Ulmo and Aulë say they will build ships that can sail into Valinor so that Men and Eldar can come home.

The way Tolkien writes it, it’s unclear whether he means for the “children” to come home to heaven, or something a little more fairy tale-esque, like the Elysian Fields of Greek Mythology fame or Valhalla of the Norse. In any case, it’s a clunky bit of logic. I find it fascinating to see how Tolkien began devising the world, but I agree with Christopher that this level of detail is unnecessary for the greater story.

Finally, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention one more cut—the creation of time.

“‘Lo, Danuin, Ranuin, and Fanuin are we called, and I am Ranuin, and Danuin has spoken.’ Then said Fanuin: ‘And we will offer thee our skill in your perplexity – yet who we are and whence we come or whither we go that we will tell to you only if ye accept our rede and after we have wrought as we desire (pg 217).'”

Instead of having time be attributed to the movement of the Sun and the Moon, Tolkien went much more mythological and created Tom Bombadil-type characters to create a way to understand the passing of time.

Danuin is the anthropomorphized concept of a Day, Ranuin is Month, and Fanuin is Year. They appear out of nowhere and approach the gods, offering gifts that later become this understanding of the passing of time.

Tolkien tells this tale at the end of the Hiding of Valinor because it is meant to be a passage of responsibility of the world to the next generation, the Eldar. The Valar are hiding away in Valinor, and the coming of these brothers created the concept of an “age.”

Before this moment, time didn’t exist, so the Valar just went about doing what they thought necessary, but this is also why the Eldar are immortal as well because they were born before time existed, men were born just after, so they were beholden to its aspect:

“Then were all the Gods afraid, seeing what was come, and knowing that hereafter even they should in counted time be subject to slow eld and their bright days to waning, until Ilúvatar at the Great End calls them back (pg 219).”

The brothers bestow this curse (or gift) of time and then say, “our job is done!” and peace out.

It’s curious how the brothers came into being, seeing as the Valar created everything in the world, but then again, there are deeper and unknown places in the world that others don’t know about, so this is a slight possibility; it’s just a clunky and unnecessary addition and one that even Christopher is glad he eventually cut:

“The conclusion of Vairë’s tale, ‘The Weaving of Days, Months, and Years’, shows (as it seems to me) my father exploring a mode of mythical imagining that was for him a dead end. In its formal and explicit symbolism it stands quite apart from the general direction of his thought, and he excised it without a trace (pg 227).”

Even Tolkien creates things where he looks back at it and realizes how out of sorts they are. Stand proud when you find mistakes because you know you FOUND them!

Join me next week as we jump into the last chapter of The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, “Gilfanon’s Tale: The Travail of the Noldoli and the Coming of Mankind.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Tale of the Sun and the Moon, part 2

“Everywhere did its great light pierce and all the vales and darkling woods, the bleak slopes and rocky streams, lay dazzled by it, and the Gods were amazed. Great was the magic and wonder of the Sun in those days of bright Urwendi, yet not so tender and so delicately fair as had the sweet Tree Laurelin once been; and thus whisper of new discontent awoke in Valinor, and words ran among the children of the Gods, for Mandos and Fui were wroth, saying that Aulë and Varda would for ever be meddling with the due order of the world, making it a place where no quiet or peaceful shadow could remain; but Lórien sat and wept in a grove of trees beneath the shade of Taniquetil and looked upon his gardens stretching beneath, still disordered by the great hunt of the Gods, for he had not had the heart for their mending (pg 189).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we conclude the Tale of the Sun and the Moon, and while doing so, we’ll talk about worldbuilding, and Tolkien’s penchant for detail.

We left off last week with the Valinor getting the fruit of knowledge from Laurelin and seeing that it held the light of the tree that once illuminated Valinor. It is a revelation for the Valar, but they still don’t have any way to make the illumination more global.

They contemplate for a bit while until Aulë takes Tulkas’ earlier idea:

“‘Then said Aulë: ‘Of this can I make a ship of light – surpassing even the desire of Manwë.’ (pg 186)”

Thus Aulë created the sun, and it sailed through the sky, illuminating the world, but “Ever as it rose it burned the brighter and the purer till all Valinor was filled with radiance and the vales of Eúmáni and the Shadowy Seas were bathed in light, and sunshine was spilled on the dark plain of Arvalin, save only where Ungweliantë’s clinging webs and darkest fumes atill lay too thick for any radiance to filter through (pg 188).”

They realized they had created an issue, a sun that never truly set, and the light bathed the world. One of the most central tenets of Tolkien (if you’ve read anything he had written) is that there can’t be light without darkness. The Valar recognized this as they saw that too much of a good thing (I.E., perpetual sun) eventually hurt them. They harkened back to when they had the two Valinor trees created with Ilúvatar’s themes; they sang into existence and decided to do something with the light of Silpion (the twilight tree).

Lórien sang to Silpion and touched the wound where Ungoliant sucked the life from it, and that little bit of music stirred something in the tree and got the sap moving. A single rose bloomed, holding the silver light of Silpion.

Lórien, proud of their work, “would suffer none to draw near, and this he would rue for ever: for the branch upon which the Rose hung yielded all its sap and withered, nor even yet would he suffer that the blossom to be plucked gently down… (pg 191).”

Both of these instances I wrote about earlier matter when we talk about the Valar. They show their ignorance, Hubris, and their childishness. Aulë has no problem stealing ideas from Tulkas and making them his own, notwithstanding that he also claimed to create the Sun. However, that was a group effort to stumble upon a solution, and Aulë only built the last portion, which would sail across the sky.

Meanwhile, the pranks of Melkor lead him to be imprisoned, but because the other Valar are creating and not pranking, they are above reproach.

Tolkien, as Ilúvatar, created these Vala in his image, just like the Christian God. By extension, these attributes were transferred to the Children of Ilúvatar, the Elves, and Men (technically, the Dwarves were created by Aulë, so they wouldn’t be considered one of the Children).

We also see the avarice of Lórien, guarding the Rose of Silpion, not letting anyone else get the benefits out of fear that they would destroy it. This reminds me of a child playing with a toy they don’t allow their friends to touch. Predictably, the branch holding the rose withers, and the rose falls from the tree, and they use the rose to make the Moon.

The result is the creation of the Sun and the Moon and the alternating cycles of celestial illumination. Tolkien matched the movement of these ships sailing the ether to our own, making his mythology nearly complete.

We’ve mentioned before that his main goal was to create a mythology for England, and at this point, he had his early history created. The Elves who went to Middle-earth have an account of murder and violence in their journey to find solace, and humans are yet to be born.

Tolkien puts both sun and night with the corresponding feelings they contain:

“‘and in memory of the waxing and waning of these Trees for twelve hours shall the Sunship sail the heavens and leave Valinor, and for twelve shall Silpion’s pale bark mount the skies, and there shall be rest for tired eyes and weary hearts (pg 191).”

The Sunship brings hope and opportunity, but if that hope and desire fail, or if one were amidst the trials, Silpion’s bark will rise in the Sunship’s place and give melancholy solace.

There is only one more point that Tolkien has to hit before he has his early mythology complete. The story of the world’s creation, moving into the first age of Middle-earth, needs one more step: to hide away the gods from the mortals before they are born.

Join me next week as we move to the penultimate chapter, The Hiding of Valinor.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Tale of the Sun and the Moon

“Then there was silence that Manwë might speak, and he said: ‘Behold O my people, a time of darkness has come upon us, and yet I have it in mind that this is not without the desire of Ilúvatar. For the Gods had well-nigh forgot the world that lies without expectant of better days, and of Men, Ilúvatar’s younger sons that soon must come. Now therefore are teh Trees withered that so filled our land with loveliness and our hearts with mirth that wider desires came not into them, and so behold, we must turn now our thoughts to new devices whereby light may be shed upon both the world without and Valinor within (pg 181).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we get back into Tolkien’s religious background as we cover the Tale of the Moon and the Sun.

We’ve come to a point in the story where Melkor has killed the Trees of Valinor, and the Noldor killed many of their kin to steal ships to chase Melkor to Middle Earth.

The Vala faced the difficulty of what they should do. Melkor had left Valinor in darkness, and the trees were dead. What should their first action be? To go after Melkor and imprison him again, or try to figure out how to bring light back to Valinor.

The Spoke to Sorontur (who later became Thorondor), the King of Manwë’s eagles, and asked him to spy on Morgoth.

“…he tells how Melko is now broken into the world and many evil spirits are gathered to him: ‘but,’ quoth he, ‘methinks never more will Utumna open unto him, and already is he busy making himself new dwellings in that region of the North where stand the Iron Mountains very high and terrible to see (pg 176).'”

So the Valar doesn’t have to worry about Melkor for the time being because he will be spending all his time trying to make a home for himself. After hearing the Eagle’s report, it’s their opinion that Melkor will not be returning to Valinor, so he is now the Noldor’s problem, which they deserve because of the transgressions they laid on their fellow kin.

So that brings them back to their other issue. How do they deal with the loss of the light of Valinor? They decide that they must build a great ship and use the remainder of the light of the Trees, and this new ship can be like the stars, but it will travel the sky and light Valinor once again.

The prospect of the ship is exciting because it calls to mind the Greek God Helios, who rode a great chariot across the sky, and that is how the sun was to rise and set. Remember that Tolkien’s ultimate work was to create new mythos and mythology for England because Spencer’s work was sub-par (to Tolkien). This ship across the sky, built by gods, was a way that he could make things unique enough to fit within his landscape of fantasy. He even had a reason for the ship to rise and set:

“Now Manwë designed the course of the ship of light to be between the East and West, for Melko held the North and Ungweliant the South, whereas in the West was Valinor and the blessed realms, and in the East great regions of dark lands that craved for light (pg 182).”

But while they built this idea, he collected mythology from other areas and brought it into his ethos. Eventually, the ship was a failure. The downfall shows that Tolkien believed he was writing the ultimate mythology because the portion he took from another culture ultimately failed.

The Vala went back to Yavanna, who had created the Trees in the first place, but she had run through the energy needed. She poured everything she had into the trees, but it was Vána (another Valar who only appears in these early iterations) who made the most significant difference:

“Now was the time of faintest hope and darkness most profound fallen on Valinor that was ever yet; and still did Vána weep, and she twined her golden hair about the bole of Laurelin and her tears dropped softly at its roots; and even where her first tears fell a shoot sprang from Laurelin, and it budded, and the buds were all of gold, and there came light therefrom like a ray of sunlight beneath a cloud (pg 184).”

The tears of love brought Laurelin back to life enough to get those sprouts. “One flower there was however greater than the others, more shining, and more richly golden, and it swayed to the winds but fell not; and it grew, and as it grew of it’s own radient warmth it fructified (pg 185).”

The fruit that grew from the tree of Laurelin grew from tears, death, and rebirth. This fruit was, for Tolkien, his introduction to the Christian ideal of the Fruit of Knowledge. Still, instead of one of the Valar eating it and causing sin, the sin has already been created. The knowledge of death, destruction, jealousy, and Hubris has already taken hold of the peoples of Middle-earth because of Tolkien’s fallen Angel Melkor.

“Even as they dropped to earth the fruit waxed wonderfully, for all the sap and radience of the dying Tree were in it, and the juices of that fruit were like quivering flames of amber and of red and its pips like shining gold, but it’s rind was of a perfect lucency smooth as a glass whose nature is transfused with gold and therethrough the moving of its juices could be seen within like throbbing furnace-fires (pg 185).”

The Valar had found the fruit of knowledge that could shine the light on the land and destroy the darkness. The fruit knew what came before, and its sole meaning was to shine the morning so that others didn’t have to carry the burden of its dark understanding.

Join me next week as we complete the Tale of the Sun and the Moon.

Elsie Jones is Coming on 08/01

Hey everyone! I’m taking a week off from writing the Blind Read Blog and focusing on some extra editing, and I wanted to give everyone a special sneak peek of the upcoming Author’s editions of the New Elsie Jones Adventures, which will kick off with Elsie Jones and the Book Pirates on 08/01 of this year!

The Elsie Jones Adventures are a children’s chapter book series where Elsie Jones finds a mysterious secret room in her local library. In that room are fifteen books that, when she reads them, she is transported into their world and adventures with those characters.

Every book has action, humor, adventure, and fun little facts, so join me on this fun adventure!

Check out that special sneak peek below:

Beyond the door was an old wooden rickety staircase leading down. The walls on either side were brick, which was unlike the rest of the library. It looked so much older than everything else.

Elsie looked around to see if she could ask anyone if she was going in the right direction. When she didn’t see anyone, she considered returning to the main desk and getting her dad to accompany her.

“But I’m in the library,” she said to herself. “Nothing ever goes wrong in the library!”

“Shhhhh!” The person hissed again.

She took a deep breath and one more look around before walking down the steps. At the bottom of the staircase, she found another room filled with books. These books, however, were far older than any of the ones upstairs. Their covers were all shades of brown and red, and the titles faded on their spines. The other thing about this room was that the smell was different too. It smelled like old books. It reminded her of her grandfather’s office, and the memory made her smile.

She scanned the shelves, looking from history book to history book. She saw all kinds of interesting books. She ran her hand across the spines, enjoying the feeling of the old bindings when something odd happened. One of the books on the shelf had a red seven on the spine, just above the title, and when she touched the book, the red seven began to glow.

She pulled her hand back as if the book was hot and then looked at the title: Treasure Island by Robert Luis Stevenson.

“Why is there an adventure about Pirates in the history section?” Elsie asked.

She turned around, expecting the person to shush her again but didn’t hear anything. In fact, she thought she was alone down here in this old History section.

She paused just before touching the book again, but her curiosity got the better of her. It had a faded brown spine, the same as the ones next to it, but on the book’s cover, another bright shiny red seven glowed in the upper right corner.

“Whoa!” she exclaimed.

Excited, she flipped the cover open and saw an intricate drawing of a giant Pirate ship and a pirate with a pegleg and a large hat who held a sword in his hand.

The book was heavy, so she laid it on the ground for a better look. As she leaned over and flipped through it there were awesome color pictures of pirates fighting with swords, burying treasure, and sailing through storms. She also saw photos of a young boy doing all these things with the pirates.

“Oh, that would be so cool!” Elsie said.

“Squire Trelawney, Dr. Livesey, and the rest of these gentlemen having asked me to write down the whole particulars about Treasure Island,” She read.

Then something strange happened; the moment she spoke the pages started to turn on their own, flipping faster and faster until the pictures seemed to move. The pirates jumped on the ship and fought each other with their cutlasses. Elsie leaned back in surprise. One of the pirates turned to her and waved his hand, gesturing for her to join them.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Darkening of Valinor

“Now Melko having despoiled the Noldoli and brought sorrow and confusion into the realm of Valinor through less of that hoard than aforetime, having now conceived a darker and deeper plan of aggrandisement; therefore seeing the lust of Ungwë’s eyes he offers her all that hoard, saving only the three Silmarils, if she will abet him in his new design (pg 152).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we’re going to dive into the philosophy of Tolkien’s world through the events of The Darkening of Valinor.

We’ve discussed it before, but Tolkien relied heavily on his Christian background while creating this mythology. He wanted something new and unique for England, and as we know, mythologies are all origin stories.

The people of Middle-earth (Elves, Men, Dwarves, etc.) are all iterations of our evolution, and it shows from the beginning of The Book of Lost Tales that Tolkien intended for Middle-earth to be a precursor to Earth (he even calls it Eä in the Silmarillion).

Because this is mythology, Tolkien brings his version of the afterlife and the angels he introduces to the world. Melkor, who is Tolkien’s version of Satan, is ostracized for stealing the Eldar gems and Silmarils. Cast out of Heaven as it were:

“Now these great advocates moved the council with their words, so that in the end it is Manwë’s doom that word he sent back to Melko rejecting him and his words and outlawing him and all his followers from Valinor for ever (pg 148).”

But it was still during this period that Melkor was mischievous, but he had not transitioned to evil yet, even after being cast out of Valinor. So instead, he spent his time trying to create chaos using his subversive words:

“In sooth it is a matter for great wonder, the subtle cunning of Melko – for in those wild words who shall say that there lurked not a sting of the minutest truth, nor fail to marvel seeing the very words of Melko pouring from Fëanor his foe, who knew not nor remembered whence was the fountain of these thoughts; yet perchance the [?outmost] origin of these sad things was before Melko himself, and such things must be – and the mystery of the jealousy of Elves and Men is an unsolved riddle, one of the sorrows at the world’s dim roots (pg 151).”

The great deceiver has been created out of jealousy and anger for these beings of Middle-earth, believing that they were given more than their fair share and his own acts were ruined from the beginning of the Music of the Ainur.

But what did the Elves do? Was there anything they received that made anything Melkor did excusable?

“And at the same hour riders were sent to Kôr and to Sirnúmen summoning the Elves, for it was guessed that this matter touched them near (pg 147).”

It was nothing that they did, but the fact that the Valar treated them as equals to the Valar and Melkor’s slights against them weren’t considered pranks he felt they were, so his anger grew.