Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2, Túrin Turambar Final Thoughts

“Turambar indeed had followed Nienóri along the black pathways to the doors of Fui, but Fui would not open to them, neither would Vefántur. Yet now the prayers of Úrin and Mavwin came even to Manwë, and the Gods had mercy on their unhappy fate, so that those twain Túrin and Nienóri entered into Fôs’Almir, the bath of flame, even as Urwendi and her maidens had done in ages past before the first rising of the Sun, and so were all their sorrows and stains washed away, and they dwelt as shining Valar among the blessed ones, and now the love of that brother and sister is very fair; but Turambar indeed shall stand beside Fionwë in the Great Wrack, and Melko and his drakes shall curse the sword of Mormakil (pgs 115-116).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we’ll give some final thoughts on Turambar and the Foalókë, including some semantics and religion, to better understand what Tolkien was trying to do in this history of Middle-earth.

I chose the opening quote of this essay because I think that religion is at the cornerstone of everything that Tolkien was doing at this point in his career.

This story iteration was a mixture of the third and fourth drafts Tolkien’s son, Christopher, edited together. That quote that starts this essay has so much to unpack, and it’s all about meaning, life, and the afterlife.

A few sentences above that quote, we find that Úrin and Mavwin go to Mandos after dying, heaven in this world. Úrin spent his life struggling against Melko as a thrall and a man who tried to better those around him. Mavwin tried to do her best for all of her children and for the town she lived in. So, it makes sense that these two would be gifted an afterlife.

Túrin and Nienóri were denied entrance to Mandos, so they went to Fui and Ve, which are Purgatory and Hell, respectively. Strangely enough, they are also denied entrance to these places of the afterlife. So what does that leave them?

This might be the first time in the history of Middle-earth that the possibility of a spirit (or spirits) wandering the lands comes into play. The Valar looks at these two humans and decides they are not worthy of any afterlife because of their actions. Túrin with the deaths he caused, and Nienóri because she had a child with her brother and killed herself.

Judgement rains down on the two despoiled people from every direction. They hold themselves accountable and let depression and hatred of their actions lead them to suicide. At the same time, they feel the disgust of those around them, and even the Gods (in the form of Valar) tell them that they are not worthy of the afterlife because of their actions.

You must remember that Humans at this time were the only conscious beings living on Middle-earth who actively died (Elves could die from martial means, but otherwise, they are immortal, and the Valar are eternal gods), so damning a human to eternal torment of staying in the place of their transgressions and forever having those reminders was a cruel punishment.

This brings me to my next point: Tolkien wrote this as a tragedy of the tallest order, much more so than the story of Beren and Lúthien. To illustrate this, here is the literary definition of tragedy from Encyclopedia Britannica (forgive the pedantry).

“Although the word tragedy is often used loosely to describe any sort of disaster or misfortune, it more precisely refers to a work of art that probes with high seriousness questions concerning man’s role in the universe.”

Tolkien saw some horrible things during his lifetime. He spent years of his youth in the trenches of World War I and saw what bullets, mortars, and Mustard Gas did to people—this time had an indelible mark on his life and his writing. Many people think that his battle scenes are where his time at the Front comes into play, but to be quite honest, that could be imagination (I have written battle scenes, as have many authors who have never seen war).

I contend that what Tolkien took from World War I was instead a deeper perspective on humanity and tragedy.

The humans in Middle-earth had to come to grips with a shorter life span and thus had to work through their emotions of the knowledge of death faster than the Elves or the Valar.

That understanding echoes the real-life experiences in war and better explains the impetuousness of Túrin.

The Elves and Valar had the time to contemplate their actions and trajectories, but humans were born knowing they would die. That knowledge, living with beings that knew they couldn’t die, affected humans strangely. They strove to make a name for themselves; they aimed for meaning and legacy. Once someone gets a taste of notoriety, pride enters, and there is no more tremendous anger than damaged pride.

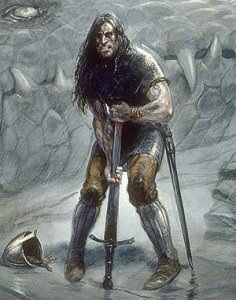

This is the start of Túrin’s fall and the beginning of his tragedy. He murders Orgof for being bullied, and though he is forgiven for this transgression, he is never able to forgive himself. His actions had to be more severe as he aged because a more significant action was the only way to make up for his earlier actions.

That is the true tragedy. Túrin, as all the people around him would probably attest, only ever wanted to help his fellow man and make the world better, but because of his past and his drive, it leads to wrong decision after bad decision, which creates murder and destruction in its wake.

Bringing this back to the definition of tragedy, this tale is only “high seriousness” and shows how mortality can change how people see the trajectory of their lives. Man’s mortality becomes the defining characteristic of their early existence on Middle-earth, and it takes them generations to come to grips with that mortality (which they never indeed do).

Then we layer on that Tolkien meant for these tales to be a mythology for England, kind of a pre-history of our current lives, and it shows how our ancestors dealt with fame, love, and mortality, which informs us as a culture and species moving forward.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2; Túrin’s last tragedy

“There did she stay her feet and standing spake as to herself: ‘O waters of the forest whither do ye go? Wilt thou take Nienóri, Nienóri daughter of Úrin, child of woe? O ye white foams, would that ye might lave me clean – but deep, deep must be the waters that would wash my memory of this nameless curse. O bear me hence, far far away, where are the waters of the unremembering sea. O waters of the forest wither do ye go?’ Then ceasing suddenly she cast herself over the fall’s brink, and perished where it foams about the rocks below; but at that moment the sun arose above the trees and light fell upon the waters, and the waters roared unheeding above the death of Nienóri (pg 109-110).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we conclude the tale of Turambar and the Foalókë and experience the last tragedies of Turambar’s life.

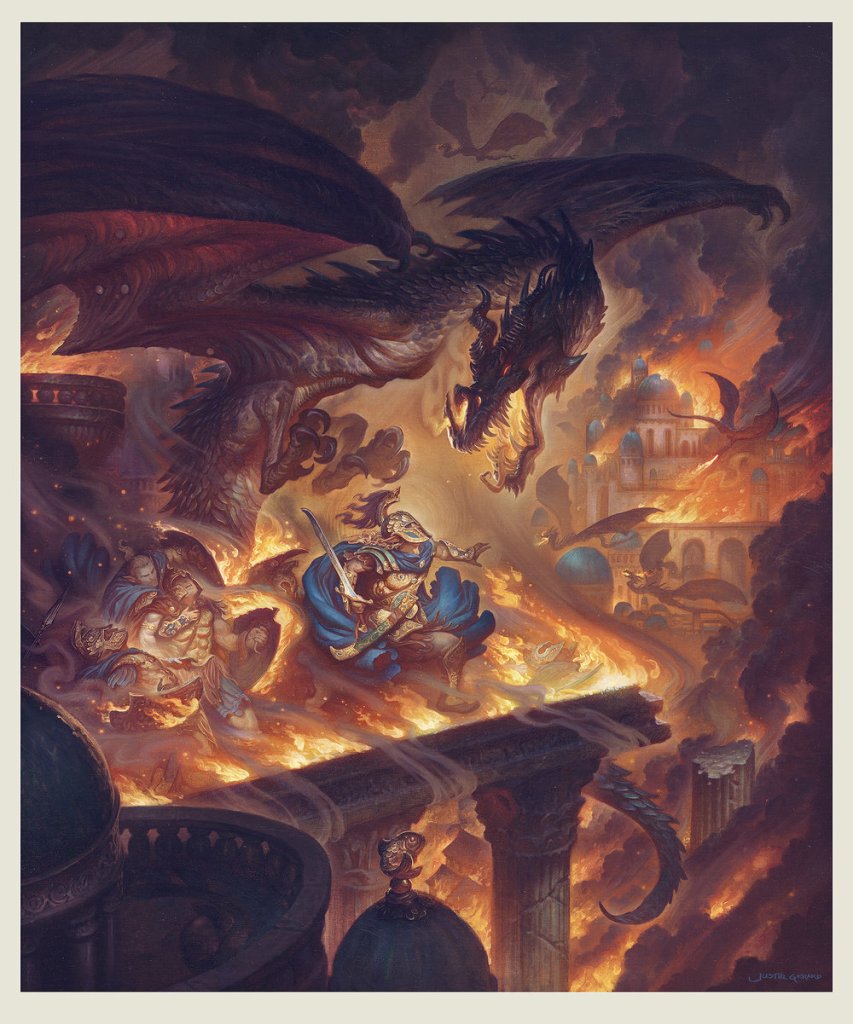

We left off last week with Turambar and Níniel deciding to ride out against the Foalókë, Glorund, to kill the drake. They gathered with them a group of men desperate to rid their land of the terrible beast, but on the way to the drake, they slowly abandoned the mission, leaving only a handful of mercenaries left, and “Of these several were overcome by the noxious breath of the beast and after were slain (pg 104).”

Eventually, only Turambar and Níniel were left to face the beast. “Then in his wrath Turambar would have turned his sword against them, but they fled, and so was it that alone he scaled the wall until he came close beneath the dragon’s body, and he reeled by reason of the heat and of the stench and clung to a stout bush.

“Then abiding until a very vital and unfended spot was within stroke, he heaved up Gurtholfin his black sword and stabbed with all his strength above his head, and that magic blade of the Rodothlim went into the vitals of the dragon even to the hilt, and the yell of his death-pain rent the woods and all that heard it were aghast (pg 107).”

The death of Glorund would seem like a cause for celebration, but unfortunately, Turambar’s efforts to end the scourge of the great worm only ended up in more tragedy.

His death was foretold from his early mistakes, and if he had only taken a little more time and been less impetuous, his life wouldn’t have ended up the way it was. Turambar is an echo of Hotspur, the firey prince of Shakespeare’s histories, where he has everything going for him, but because of his temper and strong desires, his life is degraded.

So how could Turambar’s life degrade from killing the drake, you might ask? Well, he passes out next to the Foalókë, and when Níniel comes to find him, she thinks he died along with the dragon in mortal combat. She weeps next to Turambar. She weeps for her husband. She cries for the man who killed the dragon and saved their people. But her weeping wakes Glorund for one last gasp.

“But lo! at those words the drake stirred his last, and turning his baleful eyes upon her ere he shut them for ever said: ‘O thou Nienóri daughter of Mavwin, I give thee joy that thou has found thy brother at last, for the search hath been weary – and now is he become a very mighty fellow and a stabber of his foes unseen (pg 109).”

Glorund died with these words, but what fell with the great beast was the glamor he held over Nienóri. She was suddenly aware of who she was and who Túrin was. Realization bombarded her that she had been married to her brother and had children with him. Aghast at the knowledge, she heads off to a waterfall called the Silver Bowl, contemplative. But instead of Nienóri coming to terms with the events of the last number of years, she is overwhelmed, and we get the quote that opens this essay.

Túrin wakes and quickly realizes that she is gone. He heads back to the village where the people already know the secret of their king and queen, and Túrin pulls it out of them. This being Túrin and his tragic story, he responds how you would expect him to:

“So did he leave the folk behind and drive heedless through the woods calling ever the name Níniel, till the woods rang most dismally with that word, and his going led him by circuitous ways ever to the glade of Silver Bowl, and none had dared to follow him (pg 111).”

Túrin turns to his sentient sword and begs for the only absolution his troubled life could understand.

“‘Hail Gurtholfin, wand of death, for thou art all men’s bane and all men’s lives fain wouldst thou drink, knowing no lord or faith save the hand that wields thee if it be strong. Thee I only have now – slay me therefore and be swift, for life is a curse, and all my days are creeping foul, and all my deeds are vile, and all I love is dead (pg 112).'”

“and Turambar cast himself upon the point of Gurtholfin, and the dark blade took his life (pg 112).”

The tale doesn’t end here, however; Tolkien switches us back to Mavwin and her search for her children. She wept and went into the woods, and the region of Silver Bowl became haunted by their past and presence.

Tolkien also lays on some of his Christianity, which is notably absent in the later editions:

“Yet it is said that when he was dead his shade fared into the woods seeking Mavwin, and long those twain haunted the woods about the fall of Silver Bowl bewailing their children. But the Elves of Kôr have told, and they know, that at last Úrin and Mavwin fared to Mandos, and Nienóri was not there nor Túrin thier son (pg 115).”

Both the children ended up as spirits because their transgressions forbade them from the afterlife.

Join me next week as we dive more into the religion of the story and break down just what Tolkien was going for with such a horrifically tragic story.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2, Turambar’s Fourth Tragedy

“Now as the days passed Turambar grew to love Níniel very greatly indeed, and all the folk beside loved her for her great loveliness and sweetness, yet was she ever half-sorrowful and often distraught of mind, as one that seeks for something mislaid that soon she must discover, so the folk said: ‘Would that the Valar would lift the spell that lies upon Níniel (Pg 101).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we continue with Túrin’s tale as it turns from dark to strange and learn how his bad decisions lead to his next tragedy.

This portion of the tale switches gears and focuses on Túrin’s mother, Mavwin, and his sister, Nienóri. We know already from the previous portions of the story that Mavwin and Nienóri left Hislómë and went down to try and find Túrin in Tinwelint’s hidden home, but when they got there, they found that Túrin had fled.

“Now the tale tells not the number of days that Turambar sojourned with the Rodothlim but these were many, and during that time Nienóri grew to the threshold of womanhood (pg92).”

Being a young lady, Nienóri would not accept being a ward of Brodda, so she convinced her mother that she would join Mavin on the sojourn to Tinwelint and to find her long-lost older brother.

They went through perils to get there, braving the creatures of the wilds, and then when they finally reached the Elven home, they found that Túrin was gone. They received conflicting reports that he was either dead or had been captured by Orcs and was made a thrall, like his father before him.

They soon find that the Foalókë (dragon) Glorund is in the area and might have Túrin in his grasp, so Mavwin and Nienóri steel themselves and head out to face the Foalókë and try to save him.

During this time, there were some exciting transitions that Tolkien was still working through (which is apparent in the notes). Túrin had changed his name to Turambar (or Mormakil) when he became an outlaw, which is at the same time Mavwin and Nienóri are looking for him. So when they questioned the people of the wood looking for Túrin, many of the Rodothlim they questioned didn’t know who Túrin was, because they only knew him as The Mormakil or Turambar. Without this comedy of errors, they wouldn’t have had to venture out and try to fight against Glorund because Turambar (as we’ll call him moving forward) had already escaped.

But alas, they sought the Foalókë and were caught in his glamor: “‘Seek not to cajole me, woman,’ sneered that evil one. ‘Liever would I keep they daughter and slay thee or send thee back to thy hovels, but I have need of neither of you.’ With those words, he opened full his evil eyes, and a light shone in them, and Mavwin and Nienóri quaked beneath them, and a swoon came upon their minds, and them seemed that they groped in endless tunnels of darkness, and there they found not one another ever again, and calling only vain echoes answered, and there was no glimmer of light (pg 99).”

Oof. This passage is probably as close to horror as anything in Tolkien. The dragon has put their minds in a cage, and mother and daughter never see each other again. They don’t recognize each other, and this transcends into the rest of the story. We follow Nienóri as she leaves and ends up living with wood rangers. In the woods, “she seemed to herself to awake from dreams of horror nor could she recall them, but their dread hung dark behind her mind, and her memory of all past things was dimmed (pg 99).”

For the rest of the tale, Tolkien writes Nienóri in this fashion. Confused and haunted, as if something is beyond her understanding or grasp, and this confusion leads to Turambar’s next tragedy.

Turmabar eventually gets to the hovel where the wood rangers live and he sees a beautiful young woman whom he calls Níniel because she cannot remember her name. He calls her this because she is distraught and crying when he finds her, and Níniel means little one of tears.

Nienóri was just a baby the last time Turambar saw her, so he doesn’t recognize her, and there are copious liner notes from Tolkien himself which indicate how careful he needs to be, not to mention the name Túrin and give away the surprise. Because Turambar does not recognize her and Níniel does not remember her past, the two begin to court, which leads to the quote that opens this essay and Túrin’s next tragedy.

It seemed as though there was peace in Hisilómë, as The Foalókë didn’t know where they were hiding. For a time, there was prosperity, and “Like a king and queen did Turambar and Níniel become, and there was song and mirth in those glades of their dwelling, and much happiness in their halls. And Níniel conceived (pg 103).”

There is Turmabar’s fourth tragedy. Unbeknownst to him, he met a familiar and beautiful face in his sister, wooed and married her, then had a child through incest.

They lived in happy ignorance until a traitor found their home in the forest. Mîm the dwarf, known as Mîm the petty dwarf in The Silmarillion, betrayed their whereabouts.

The Foalókë charged out through the woods and smote some of the woodsmen. Turambar, being their chief, decided that he needed to do something.

“Now when Turambar made ready to depart then Níniel begged to ride beside him, and he consented, for he loved her and it was his thought that if he fell and the drake lived then might none of the people be saved, and he would liever have Níniel by him, hoping perchance to snatch her at least from the clutches of the worm, by death at his own or one of his liege’s hands (pg 104).”

His decision seemed to be sound reasoning at the time, but they were against a terrible foe in Glorund, the Drake who glamorized his whole family, and his wife/sister was still under that glamor. If we know anything about Turambar’s life, we know what will come next.

Join me next week as we conclude Turambar’s tale!

Blind Read Through: The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2, Túrin’s Third Tragedy

“And thereupon Turambar leapt upon the high place and ere Brodda might foresee the act he drew Gurtholfin and seizing Brodda by the locks all but smote his head from his body, crying aloud: ‘So dieth the rich man who addeth the widow’s little to his much. Lo, men die not all in the wild woods, and am I not in truth the son of Úrin, who having sought back unto his folk findeth an empty hall despoiled (pg 90).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we delve back into Túrin’s story and reach a turning point in his life. In addition, we get to experience Túrin’s third tragedy.

We left off last week with Túrin leaning into the Outlaw mentality and choosing that lifestyle in the woods and wilds. As we’ve discussed, Túrin didn’t have the easiest childhood. His father was a thrall to Melko, as were many of his people, and his sister died young. Mavwin, Túrin’s mother, sent him to live with Tinwelint as a ward to that Elven King. He lived with this idea of being an orphan his entire life, even though his mother lived and gave birth to another sister.

In his head, Túrin always felt as though others were looking at him as an outsider, so when he killed Orgol (his first tragedy), he assumed that others were judging him based on his family. It isn’t until he kills Beleg (his second tragedy) that he begins to think less of himself and his contributions to society, so he begins to slide into being an outlaw.

Túrin does not account for the area’s history and how Melko had corrupted things. After we find out about his outlaw shift, there is a meeting with the Rodothlim. To rally them for battle, “for he lusted ever for war with the creatures of Melko (pg 83),” he called for them to: “Remember ye the Battle of Uncounted Tears and forget not your folk that there fell, nor seek ever to flee, but fight and stand (pg 83).”

Túrin needs to take a history lesson. The Battle of Unnumbered Tears (later called in The Silmarillion), also known as Nirnaeth Arnoediad, was so named because of the sheer amount of dead and the Doom of Mandos.

Mandos laid down that curse because the Noldori killed their kin to go after Melko and recover the Silmarils. In that titular curse, Mandos tells the Eldar, “Tears Unnumbered ye shall shed,” In this battle, also known as the Fifth battle in the wars of Beleriand, Morgoth gains ground and begins to take over the land.

So, while Túrin is internalizing the wrongs of his life and turning to violence to assuage his conscience, he forgets that everything that caused the issues was because of the Noldor, not because of him or his deeds, horrendous as they are.

So Túrin leaned into his anger and spoke to Orodreth, a smith, for a weapon because he could no longer touch the sword he killed Beleg with. This creation deviates from what the story later became because Orodreth and not Eöl fashioned Gurthang.

“Now then Orodreth let fashion for him a great sword, and it was made by magic to be utterly black save it’s edges, and those were shining bright and sharp as but Gnome steel may be. Heavy it was, and was sheathed in black, and it hung from a sable belt, and Túrin named it Gurtholfin the Wand of Death; and often that blade lept in his hand of its own lust, and it is said that at times it spake dark words to him (pg 83).”

Orodreth tried to speak against fighting against Melko’s armies, regretting his creation of the Wand of Death, but Túrin was both craving war and trying to atone for his past indiscretions, so he went out and fought every agent of Melko he could find. He became infamous, and it did not go past Melko’s sight. Melko released a great army, “and a great worm was with them whose scales were polished bronze and whose breath was a mingled fire and smoke, and his name was Glorund (pg 84).”

Glorund killed Orodreth, who, even on his death bed, reproached Túrin, blaming him for the destruction his range had caused. Túrin tried to fight, but the dragon had powers Túrin didn’t understand, and the drake charmed Túrin, holding him in place, while Failivrin waws carried away, crying out, “O Túrin Mormakil, where is thy heart; O my beloved, wherefore dost thou forsake me (pg 86).”

She didn’t understand that he had been charmed and thought he was letting the creatures kidnap her.

Túrin was trapped there with the mind games of Glorund until finally, the dragon set him free, allowing him to go after Failivrin or seek out his mother and sister, whom he only knew as a newborn.

He decides to go after his mother, only to find she has fled Dor Lómin. In her place, she left a local high-class man named Brodda to watch over her estate, but Brodda, seeing the wealth to be had, rebranded all her cattle and property as his own.

Túrin had already killed, and now he had someone directly blame him for their misfortune (in Orodreth), and he chose the wrong path to find his mother, succumbing to Melko and Glorung’s deception.

It is at this point that Túrin forsakes morality. He is no longer trying to be an upstanding citizen. Even in his outlaw stage, his actions were to help and save others. It is here that we get the quote at the beginning of this essay, and it is here that we see Túrin’s next tragedy. He has given into his anger and hate, gone over to the dark side (forgive the crossover), and decided to go with full-fledged murder.

Moving forward in his story, he is still an outlaw, but he is no longer an outlaw for the good of the people. He is now an outlaw hell-bent on his emotional trajectory.

Join me next week as we continue on Túrin’s journey!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Turambar

“Now coming before that king they were received well for the memory of Úrin the Steadfast, and when also the king heard of the bond tween Úrin and Beren the One-handed and the plight of that lady Mavwin his heart became softened and he granted her desire, nor would he send Túrin away, but rather said he: ‘Son of Úrin, thou shalt dwell sweetly in my woodland court, nor even so as a retainer, but behold as a second child of mine shalt thou be, and all the wisdoms of Gwendheling and of myself shalt thou be taught (Pg 73).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we introduce Túrin and his tragedy while getting some commentary about Tolkien’s decision to create a story throughline instead of the history that the tale became.

Christopher begins this chapter by speaking of the timeframe of the writing itself and how his father wrote Turambar in the time between the original script of Tinúviel and the edits of that tale:

“There is also the fact that the rewritten Tinúviel was followed, at the same time of composition, by the first form of the ‘interlude’ in which Gilfanon appears, whereas at the beginning of Turambar there is reference to Ailios (who was replaced by Gilfanon) concluding the previous tale (pg 69).”

I bring this to your attention because of the profound changes Tolkien was making at the time and the apparent fact that Christopher missed when he made the assertion of Beren always being intended to be Eldar.

Ailios or Gilfanon said, shortly after his introduction, “‘Now all folk gathered here know that this is the story of Turambar and the Foalókë, and it is,’ said he, ‘a favourite tale among Men, and tells of very ancient days of that folk before the Battle of Tasarinan when first Men entered the dark vales of Hisilómë (pg 70).'”

Tolkien establishes almost immediately that this is a story about Men, not Gnomes or Elves, and it is only a few pages later that we get this passage:

“…but the deeds of Beren of the One Hand in the halls of Tinwelint were remembered still in Dor Lómin, wherefore it came into the heart of Mavwin, for lack of other council, to send Túrin her son to the court of Tinwelint, begging him to foster this orphan for the memory of Úrin and of Beren son of Egnor (pg 72).”

Here, we get a direct correlation between Beren and Úrin, one of which is a Man and the other is an Elf in the established setting. To go even further, in the opening quote of this essay, Tolkien states that Beren and Egnor were friends, and before this passage, in early Tolkien, there was no love lost between Elves and Men. This is the first instance of the earlier works where an Elf and a Man were friends.

I contend that this was an accident on Tolkien’s part because he was already beginning to think of Beren and Egnor as Men. After all, it fits the story so much better. There is even a passage where Egnor is “akin to Mavwin.” Egnor is Beren’s father, and Mavwin is Túrin’s mother, thereby stating that Egnor was, at the very minimum, a half-elf, but such things never existed in Tolkien. (You might remember Elros and Elrond, who were born half-elves; however, the Vala made them decide which side they were to fall on, and Elros became a man and founded the Númenóreans and Elrond became an Elf…and we know how that story ends)

Tolkien also brings back the Path of Dreams, or Olórë Mallë, to explain how Ailios (Gilfanon) knows these stories firsthand (there is a reference that he also knows the story of the fall of Gondolin: “and I knew it long ere I trod Olórë Mallë in the days before the fall of Gondolin (pg 70).” The more that I read of these Lost Tales, the more I understand why Tolkien took Gilfanon out of the story, and why he also took out the transitions.

Tolkien initially wanted these stories to flow into one another with a central story hub (think Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man) because he was worried that people would not be interested in the dry history of a land that didn’t exist. To tell this tale in a “Hobbit” style might make it more accessible to the everyday reader. However, he ran into the problem of how to make it work. He knew who Eriol was, and there were plans for him (which I believe will come to light in the last chapter of The Book of Lost Tales, part 2), but how does he get the surrounding characters into the work? The people who tell the tale? Well, he created things like Olórë Mallë, a sleep bridge that can get men (and only men apparently, as no Elves needed it because of their immortality) to different areas of space and time. He also created spaceships (literally ships that could sail across the sky) but decided to limit that to elevate a single character, Eärendil, to a godlike being as he sails his ship Vingilot across the sky.

These ideas were a means to an end, and he only used them to tell the story. He eventually realized that these plot devices were only taking away from the story instead of enhancing it, but his quandary was that to take them away removes all credence of the story that was being told. For this reason, I believe Tolkien took out the transition pieces with Eriol learning the histories.

That leads us right into Turambar because, as Ailios describes Úrin and how he knew Beren and his travails. Mavwin, Túrin’s mother and Úrin’s wife, decided that Túrin would be safer staying with Tinwelint, than he would up north with the threat of Melko.

Thus, Túrin’s story begins.

“Very much joy had he in that sojourn, yet did the sorrow of his sundering from Mavwin fall never quite away from him; great waxed his strength of body and the stoutness of his feats got him praise wheresoever Tinwelint was held as lord, yet he was a silent boy and often gloomy, and he got not love easily and fortune did not follow him, for few things that he desired greatly came to him and many things at which he laboured went awry (pg 74).”

Join me next week as we continue the tragedy of Túrin Turambar!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Tale of Tinúviel, commentary

“In the old story, Tinúviel had no meetings with Beren before the day when he boldly accosted her at last, and it was at that very time that she led him to Tinwelint’s cave; they were not lovers, Tinúviel knew nothing of Beren bu that he was enamoured of her dancing, and it seems that she brought him before her father as a matter of courtesy, the natural thing to do (pg 52).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we’ll briefly cover Christopher’s commentary on The Tale Of Tinúviel and give some final thoughts on the story.

Much of what Christopher covers (Christopher is J.R.R. Tolkien’s son and editor. This book is posthumously published, and Christopher both compiled it and edited it) in his lengthy comments following the Tale of Tinúviel are the same or very similar to everything that I have covered in the previous Blind Reads, so we’ll speak about the most critical insights and give some context.

Before we jump into that, however, Christopher included a second draft (or at least pieces) of The Tale of Tinúviel just after the first edition and before his comments.

“This follows the manuscript version closely or very closely on the whole, and in no way alters the style or air of the former; it is, therefore, unnecessary to give this second version in extenso (pg 41).”

The most significant change that I noticed was the nomenclature. The forest’s name changed to Doriath, and the names Melian and Thingol are introduced here for the first time.

We also have the adjustment of Beren’s father from Egnor to Barahir and Angamandi to Angband. Most importantly, we first mention Melko as Morgoth (The Sindarin word for Melkor).

This last adjustment may seem like an alteration of monikers to streamline the narrative; however, knowing how The Silmarillion was published and the extensive lists of names, not to mention the number of names in each language many of the characters had, we know he did this intentionally.

Many people assume (and rightly so because the theory has become so ubiquitous) that Tolkien built a language (Elvish) and then developed a story and world based on that language. This theory makes a certain amount of sense because he was a linguist. Still, read these books (or, more importantly, Christopher’s annotation). You’ll understand that the world-building and the language came conjointly because of Tolkien’s desire to tell a fairy tale that would become England’s own. It was all supposed to start with this first story: The Tale of Tinúviel.

The names evolved because Tolkien was developing his language and the world the story took place in, and the names he originally used no longer made sense.

A prime example of this is in the second version of the story, “Beren addresses Melko as ‘most mighty Belcha Morgoth (pg 67).'” I’ll let Christopher explain:

“In the Gnomish dictionary Belcha is given as the Gnomish form corresponding to Melko, but Morgoth is not found in it: indeed this is the first and only appearance of the name in the Lost Tales. The element goth is given in the Gnomish dictionary with the meaning ‘war, strife’; but if Morgoth meant at this period ‘Black Strife’ it is perhaps strange that Beren should use it in flattering speech. A name-list made in the 1930s explains Morgoth as ‘formed from his Orc-name Goth ‘Lord of Master’ with mor ‘dark or black’ prefixed, but it seems very doubtful that this etymology is valid for the earlier period (pg 67).”

Tolkien was evolving and creating new languages for the Eldar and the Orcs, Dwarves, and Valar. Beyond that, he was developing dialects within these languages, so a Sindarin name would be different from a Noldoli name, which is where many people get confused about the number of names in The Silmarillion and how the rumor got started that Tolkien created the languages first and the world second. The above quote is the irrefutable proof (not to mention the extensive changes to The Lost Tales).

We can see the linguistic changes Tolkien is making, which in turn changes the story’s core, but there is some very interesting world-building that Tolkien has done in the augments between drafts.

The first example surrounds the Simarils; “The Silmarils are indeed famous, and they have a holy power, but the fate of the world is not bound up with them (pg 53).”

Tolkien understood the Maguffin (a plot device that sets the characters into motion and drives the story) early on. Still, his original intention was to tell the tale of two lovers, he and Edith, but in the names of Beren and Lúthien (Tinúviel). What he came to realize as he went through drafts and started to build the history of the world (this second version was also the first mention of Turgon the King of Gondolin because Tolkien had begun working on the story The Fall of Gondolin before he went back to the second draft of the Tale of Tinúviel), was that there needed to be a through line to bring the different tales together into one single history, rather than having a bunch of disparate short stories spattered throughout history. The Silmarils became that Maguffin. They grew in mystery and power in his mind. The tale of Valinor became the precursor and introduction to the power that the Silmarils contained so that they might tell a much larger story and have the whole of the world seeking the power they held (much like the One Ring in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings).

The Tale of Tinúviel is a fascinating addition to the Legendarium, but it does feel a little one-note beside its later counterpart, Of Beren and Lúthien. What is most interesting is the fairy tale manner in which Tolkien tells the tale. The first big bad we see is a cat who captures our hero and makes him hunt for them because they’re lazy cats. This anthropomorphized creature is a common theme in fairy tales, and Tevildo never truly poses a real threat, especially when Huan the Hound shows up. Then, when Tinwelint imprisons Tinúviel in a tall tower to keep her from going after her love, we get impressions of all the old Anderson Fairy Tales. In this early version, it is apparent that Tolkien was going for a fairy tale vibe (which in fact was his original intention before realizing that he wanted to make it more realistic, more gritty), but instead of eventually disneyfying it, he went deeper and darker and turned the tale into something bold and breathtaking, and seeing the transformation is something to behold.

We’ll take a week off before returning to the next story, “Turambar and the Foalókë.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Tale of Tinúviel, conclusion

“Lo, the king had been distraught with grief and had relaxed his ancient wariness and cunning; indeed his warriors had been sent hither and thither deep into the unwholesome woods searching for that maiden, and many had been slain or lost for ever, and war there was with Melko’s servants about all their northern and eastern borders, so that the folk feared mightily lest that Ainu upraise his strength and come utterly to crush them and Gwendeling’s magic have not the strength to withold the numbers of the Orcs (pg 36).”

Welcome back to another Blind read! This week, we finish The Tale of Lúthien and reveal more differences between The Book of Lost Tales and The Silmarillion.

We left off last week with Lúthien and Huan saving Beren from Tevildo and the cats. After escaping, they retreated and recovered, but there was still that everlasting desire to go and get the Silmaril back, so they devised a plan.

“Now doth Tinúviel put forth her skill and fairy-magic, and she sews Beren into this fell and makes him to the likeness of a great cat, and teaches him how to sit and sprawl, to step and bound and trot in the semblance of a cat… (pg 31).”

They go to Angamandi and the court of Melko, where they come into contact with Karkaras (an early version of Carcharoth), who was suspicious of Lúthien, but her disguise on Beren held. Lúthien played her magic on the great wolf and put him to sleep “until he was fast in dreams of great chases in the woods of Hisilómë when he was but a whelp… (pg 31).”

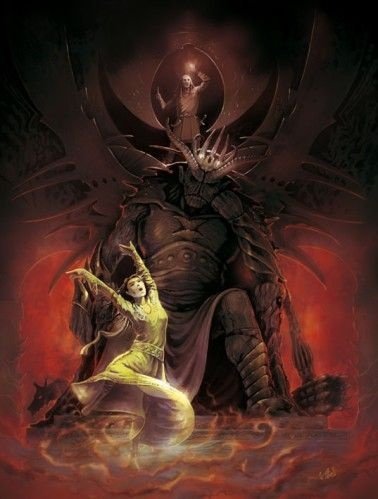

Both Lúthien and Beren make their way to Melko’s throne room, filled with cats and creatures, and Beren blended in with them, and took up a “sleeping” position underneath Melko’s throne. Lúthien on the other hand stood with pride before the Ainu, “Then did Tinúviel begin such a dance as neither she nor any other sprite or fay or elf danced ever before or has done since, and after a while even Melko’s gaze was held in wonder (pg 32).”

Everyone in the chamber, all the cats, thralls, Fay, and even Beren, fell asleep while listening to Tinúviel’s Nightingale voice. Her movements were just as hypnotizing, “and Ainu Melko for all his power and majesty succumbed to the magic of that Elf-maid, and indeed even the eyelids of Lórien had grown heavy had he been there to see (pg 33).”

Tinúviel woke Beren, careful to let everyone else continue to sleep. “Now does he draw that knife that he had from Tevildo’s kitchens and he seizes the mighty iron crown, but Tinúviel could not move it and scarcely might the thews of Beren avail to turn it (pg 33).”

They eventually pry one Silmaril off the crown, but Beren goes for a second one in his greed, only to break his blade and wake Melkor. Tinúviel and Beren fled Angamandi, pursued by Karkaras, the Great Wolf. They battled, and Karakaras bit off Beren’s hand bearing the Silmaril.

But, “being fashioned with spells of the Gods and Gnomes before evil came there; and it doth not tolerate the touch of evil flesh or of unholy hand (pg 34).” So Karkaras began to be burned alive from the inside out and screamed for all he had. The screams of the Great Wolf woke the castle, and Beren and Tinúviel fled for their lives.

They ran with an entire Orc army of Melko on their trail and had many encounters with them but eventually “stepped within the circle of Gwendeling’s magic that hid the paths from evil things and kept harm from the regions of the woodelves (pg 35).” Otherwise known as the Girdle of Melian.

They make their way to the king, and we get the quote that opens this essay, but Tinwelint saw no Silmaril, so they related the tale, and Beren stood before the king and said, “‘Nay, O King, I hold to my word and thine, and I will get thee that Silmaril or ever I dwell in peace in thy halls (pg 38).'”

So Beren went back out into the wilds to find the body of Karkaras and claim the Silmaril, but he didn’t go alone. “King Tinwelint himself led that chase, and Beren was beside him, and Mablung the heavy-handed, chief of the king’s thanes, leaped up and grasped a spear (pg 38).”

They eventually came upon a vast army of wolves, and among them was Karkaras, still alive but howling in agony. There was a great battle, “Then Beren thrust swiftly upward with a spear into his (Karkaras) throat, and Huan lept again and had him by a hind leg, and Karkaras fell as a stone, for at that same moment the king’s spear found his heart, and his evil spirit gushed forth and sped howling faintly as it fared over the dark hills to Mandos; but Beren lay under him crushed beneath his weight (pg 39).”

Beren was mortally wounded beneath Karkaras, and they tried to nurse him back to health. In the meantime, Tinwelint and Mablung found the Silmaril in Karkaras’ body. Tinwelint refused to take it unless Beren gave it to him to honor the fallen warrior, so Mablung grabbed the Silmaril and handed it to Beren, who, with his dying breath, said, “‘Behold, O King, I give thee the wondrous jewel thou didst desire, and it is but a little thing found by the wayside, for once methinks thou hadst one beyond thought more beautiful, and she is now mine (pg 40).'”

The tale ends with Beren dying, and we get a short interlude of Vëannë telling Eriol that there were many other tales of Beren coming back to life but that the only one she thought was true was the tale of the Nauglafring, otherwise known as the Necklace of the Dwarves.

The tale’s bones are the same all the way through, with some very significant character changes, like the addition of Celegorm and Curufin and the subtraction of Tevildo. Still, quite honestly, these things are entirely necessary because, on its own, this is just a tragic tale. When you add the other elements, the world expands, and the characters gain more agency. Suddenly, Beren’s quest affects far more than just the players in the story, and we get a much broader realization of what Beleriand is, was, and will become.

Join me next week for a short second edition of this tale, some commentary, and some final thoughts!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2; The Tale of Tinúviel, cont.

“Now all this that Tinúviel spake was a great lie in whose devising Huan had guided her, and maidens of the Eldar are not wont to fashion lies; yet have I never heard that any of the Eldar blamed her therein nor beren afterward, and neither do I, for Tevildo was an evil cat and Melko the wickedest of all beings, and Tinúviel was in dire peril at their hands (pg 27).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! We left off last week with Beren getting captured by Tevildo, Prince of Cats, and Lúthien escaping the tower her father imprisoned her in to go and find and free Beren from his thralldom.

Before the story, let’s review what happened in The Silmarillion.

Lúthien escaped from Doriath and chased after Beren, but where there are cats in The Book of Lost Tales, The Silmarillion had Wolves. Beren was captured by Sauron, the Master of Wolves (many of his minions in this story were werewolves, and he even commanded the Wolf King Carcharoth), and on her way to find him, Lúthien meets up with Huan, the Hound of Valinor.

Huan takes Lúthien to his masters, Celegorm and Curufin, who were Fëanor’s sons (Eldar who swore to get the Silmarils back at the cost of all else). The Book of Lost Tales is a significant departure from the older story because these two brothers played a nefarious role in the remaining history of Beleriand. They caused strife and trouble for our heroes many times and generally stood in the way only because of their oath, and they never appear in the earlier version.

This deception is the first instance of their devious natures. They instructed Huan to bring Lúthien before them and once there, Celegorm devised a plan to marry her because of her beauty, but more importantly because of her lineage. Celegorm was seeking power, plain and simple. He tricks Lúthien, brings her to Nargothrond, and imprisons her until his plan can be complete.

Here, Huan felt pity for Lúthien, who only wanted to save her love, and felt disgust for his master. Huan frees Lúthien, leading her to Angband to confront Sauron and free Beren.

When they get there, Sauron sends his werewolves out to kill them, but Huan kills them one by one. Sauron then shapeshifts and changes himself into a werewolf (doubtless being one of those quintessential bad guys who say, “If you want something done right, you gotta do it yourself.”), and heads out to meet them. There is a pitched battle, with Sauron changing into different shapes and trying other tactics. Still, eventually, Huan defeats him, and Sauron flees in the form of a Vampire after leaving the keys to the prisons for Huan and Lúthien to take.

This fight shows the absolute power of Huan. Sauron gained strength and influence over the remaining years of his life, but the fact that Huan and Lúthien were able to best him in battle when, later on, it took armies to stand up to him is a testament to Huan’s strength and Lúthien’s ingenuity.

They freed Beren and fled Angband, only to come across our favorite dastardly Eldar, Celegorm, and Curufin. They battled, and Beren won, deepening their shame and anger. Not only were the great sons of Fëanor defeated, but a human bested them to boot!

Beren then snuck back to Angband after both Huan and Lúthien slept, determined to get the Simaril and prove his worthiness, but when they woke and found him gone, they disguised themselves as a vampire and werewolf and went after him. They got to Morgoth’s chambers, and Lúthien used her magic to put everyone to sleep and Beren cut a Silmaril from Morgoth’s crown before escaping from the stronghold.

As they exited, Carcharoth, the King of Wolves jumped out and attacked them, biting off Beren’s hand that held the Silmaril and thus halting their quest. Huan summoned The Eagles of Manwë (you might remember these majestic creatures from the end of The Return of the King when they rescued Frodo and Sam from Mount Doom), and they escaped from Angband.

In The Book of Lost Tales, Sauron is not present. Instead, it’s Tevildo who has Beren captured. Lúthien still meets up with Huan, but we have a sort of natural cat-and-dog relationship there:

“None however did Tevildo fear, for he was as strong as any among them, and more agile and more swift save only than Huan Captain of Dogs. So swift was Huan that on a time he had tasted the fur of Tevildo, and though Tevildo had paid him for that with a gash from his great claws, yet was the pride of the Price of Cats unappeased and he lusted to do a great harm to Huan of the Dogs (pg 21).”

Tinúviel travels with Huan to Angamandi (the early version of Angband) and finds a resting cat sentry just before its gates. Tinúviel asks to speak with Tevildo and plays to the guard’s pride to get her in to gain an audience.

When she is brought before Tevildo, she asks to speak with him privately, but he is not humored:

“‘Nay, get thee gone,’ said Tevildo, ‘thou smellest of dog, and what news of good came ever to a cat from a fairy that had dealings with dogs (pg 24)?”

Tinúviel sweet-talks her way in and spies Beren in the kitchen doing his thrall duties. She speaks loudly, letting Beren know that she’s there, and then we get the opening quote of this essay, where she divulges Huan’s plan: Huan is hurt and helpless just outside in the forest, the cats must kill him!

“Now the story of Huan and his helplessness so pleased him (Tevildo) that he was fain to believe it true, and determined at least to test it; yet at first he feigned indifference (pg 27).”

Tevildo and a small group of Cats went out to try and end Huan, only to fall into the trap. Huan killed all but Tevildo, who barely escaped and lost his golden collar before fleeing up a tree.

Tinúviel took the golden collar and brought it before Tevildo’s court and got all of his prisoners released, along with a curiously named Gnome.

“Lo, let all those of the folk of the Elves or of the children of Men that are bound within these halls be brought forth,’ and behold, Beren was brought forth, but of other thralls there were none, save only Gimli, an aged Gnome, bent in thraldom and grown blind, but whose hearing was the keenest that has been in the world, as all songs say (pg 29).”

This name was undoubtedly used again once the languages were fleshed out and Tolkien realized that Gimli was much more of a dwarven name than an Elvish name, but he doesn’t appear again in this story (that I’ve read so far), so I think it was just a name Tolkien loved.

Lúthien, Beren, and Huan escaped, and the cats were ashamed. Morgoth’s anger was so great that they lost face, and the power of the cats was never the same from then on.

We’re getting close to the end! Join me as we cover the first written ending to The Tale of Tinúviel next week!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2; Beren and Lúthien

“One day he was driven by a great hunger to search amid a deserted camping of some Orcs for scraps of food, but some of these returned unawares and took him prisoner, and they tormented him but did not slay him, for thier captain seeing his strength, worn through he was with hardships, thought that Melko might perchance be pleasured if he was brought before him and might set him to some heavy thrall-work in his mines or in his smithies. So came it that Beren was dragged before Melko, and he bore a stout heart within him nonetheless, for it was belief among his father’s kindred that the power of Melko would not abide for ever, but the Valar would hearken at last to the tears of the Noldoli, and would arise and bind Melko and open Valinor once more to the weary Elves, and great joy should come back upon Earth (Pg 14-15).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we travail the beginning of the quest for a Silmaril and the humble beginnings of the story in The Book of Lost Tales.

We left off last week with Beren heading out to get the Silmaril from Melkor’s crown to curry favor of Tinwelint and acquire Tinúviel’s hand in marriage. Immediately Beren is in dangerous land:

“Many poisonous snakes were in those places and wolves roamed about, and more fearsome still were the wandering bands of the goblins and the Orcs – foul broodlings of Melko who fared abroad doing his evil work, snaring and capturing beasts, and Men, and Elves, and dragging them to their lord (pg 14).”

Beren was nearly captured by Orcs numerous times, battling all manner of creatures on his way to Angamandi (Melkor’s hold in the Iron Mountains). “Hunger and thirst too tortured him often, and often he would have turned back had not that been well neigh as perilous as going on (pg 14).”

These travels lead us right to the quote that opens this essay. Beren angered Melkor because he represented the kinship between Elves and Men “and said that evidently here was a plotter of deep treacheries against Melko’s lordship, and one worthy of the tortures of Balrogs (pg 15).”

Beren gave Melkor a speech that seemed inspired by the Valar and moved Melkor. Rather than killing him, Melkor decided that he should be sent to the kitchen and become a Thrall of Tevildo, Prince of Cats.

I want to step back here and review what changes Tolkien made to the tale over time.

The framework of the story is the same; however, In The Silmarillion, Beren left Neldoreth (The forests of Thingol and Melian) and made his way to Nargothrond to garner the help of Finrod Felagund, Elven King. He recalled Finrod’s vow to help Barahir’s (Beren’s father) kin, and Finrod agreed to help Beren in his quest for the Silmaril.

Finrod gathered a group and disguised them all as Orcs to get close to Angband, but Sauron, the future Dark Lord, became suspicious of the group and captured them. He sent them to a deep pit and sent werewolves to kill them, which Finrod killed with his bare hands. However, he was mortally wounded and thus ended one of the great Elven Kings of legend.

Tolkien’s process of bringing in Finrod fills out the whole Legendarium much more because The Book of Lost Tales is just that, tales; disparate and singular. These are a collection of stories rattling around in Tolkien’s head which built the history of a world, but he needed connective tissue (and a lot of editing) to bring everything together.

Finrod and Fëanor’s sons, Curufin and Celegorm, become the connective tissue, rather than Tevildo, the Lord of Cats, who doesn’t appear beyond The Book of Lost Tales.

So now that Beren is in captivity, Lúthien can feel that something has gone wrong, so she goes to her mother Gwendeling (Melian) and asks her to use her magic and see if Beren still lives:

“‘He lives indeed, but in an evil captivity, and hope is dead in his heart, for behold, he is but a slave in the power of Tevildo Prince of Cats (pg 17).'”

So she went to her Father, Tinwelint, who was angered that she would want to go after Beren. She also asked her brother Dairon, who scoffed at the idea of her heading off into the wilds, so he went to Tinwelint and tattled on his sister (Daeron in The Silmarillion was an unrequited lover instead of brother, and went to Thingol (Tinwelint) to stop her, and hopefully save her. Tinwelint, in his anger, put her as far away from danger as punishment as he could:

“Now Tinwelint let build high up in that strange tree, as high as men could fashion thier longest ladders to reach, a little house of wood, and it was above the first branches and was sweetly veiled in leaves (pg 18).”

Stuck in the tree, with servants bringing her food and water and then removing the ladders so she couldn’t follow, Tinúviel’s yearning for Beren grew. She stayed up there for a while until she got a vision from the Valar that Beren was still alive and held in captivity, a thrall to Tevildo tasked with hunting for the great cats. Horrified that he was there because of her, and more importantly, the love that kept growing because she could not stop thinking of him, she devised a plan.

“Now Tinúviel took the wine and water when she was alone, and singing a very magical song the while, she mingled them together, and as they lay in the bowl of gold she sang a song of growth, and as they lay in the bowl of silver she sang another song, and the names of all the tallest and longest things upon Earth were set in that song… and last and longest of all she spake of the hair of Uinen the lady of the sea that is spread through all the waters (pg 19-20).”

Remember that the whole point of writing these tales was to build a mythology for England. You can see from reading them that Tolkien was heavily influenced by other fairy tales he read, both in preparation and for study.

Tinúviel rubbed her head in the mixture, and her hair grew to great length, much like Rapunzel did to escape her tower.

Unlike Rapunzel, Tinúviel fashioned a rope out of her hair. She refused anyone from coming up to her little tree house until she finished. Then dressed in a black cloak, she escaped and headed north to go and rescue Beren.

This part of Lúthien’s story is the tale of Rapunzel, except that Tolkien flipped the script and created a strong woman to go and rescue her man.

Join me next week as we continue the story, find the differences with The Silmarillion, and generally have a great time!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Beren’s Beginnings

“‘Why! wed my Tinúviel fairest of the maidens of the world, and become a prince of the woodland Elves – ’tis but a little boon for a stranger to ask,’ quoth Tinwelint. ‘Haply I may with right ask somewhat in return. Nothing great shall it be, a token only of thy esteem. Bring me a Silmaril from the Crown of Melko, and that day Tinúviel weds thee, an she will (pg 13).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we dive into the Tale of Tinúviel, discover the differences between The Book of Lost Tales and The Silmarillion, as we begin one of Tolkien’s greatest tales.

We left off last week setting the stage for how Tolkien adjusted over time to have the story fit into his Legendarium. This week, we’re going to learn a bit more about Beren and get started on the tale itself!

Tolkien begins the tale with the lineage of Tinúviel and Dairon, as discussed last week, and then transitions into the story itself. “On a time of June they were playing there, and the white umbrels of the hemlocks were like a cloud about the boles of the trees, and there Tinúviel danced until the evening faded late, and there were many white moths abroad (pg 10).”

This play was a favorite pastime for both Tinúviel and Dairon. Dairon would play his music, and his sister would dance and sing like a nightingale in the forests of what would eventually be known as Doriath.

“Now Beren was a Gnome, son of Egnor the forester who hunter in the darker places in the north of Hisilómë. Dread and suspicion was between the Eldar and those of thier kindred that had tasted the slavery of Melko, and in this did the evil deeds of the Gnomes at the Haven of the Swans revenge itself (pg 11).”

Beren’s Genesis is an exciting story because while Tolkien was developing it early on, Beren was an elf (or, as Tolkien called them in The Book of Lost Tales, Gnomes).

The reason I chose the above quote was twofold. The first is the change of who Beren’s father was. In the Silmarillion, Beren is the son of Barahir and a descendant of Bëor, who was the leader of the first Men to come to Beleriand.

Barahir was a noble Man (When I capitalize “Man,” I’m using it in Tolkien’s manner, meaning human) who rescued Finrold Filagund from Dagor Bragollach (the Battle of Sudden Flame, otherwise known as the Fourth Battle of Beleriand), and received Finrold’s ring, which was later an heirloom of Isildur in Númenor.

In The Book of Lost Tales, Beren’s father is a Gnome named Egnor, who came to Beleriand early and became a thrall of Melkor. He eventually escaped and fathered Beren, but there was an intense distrust of any thrall of Melkor between the Gnomes.

So then Beren, when he comes across his Nightingale Tinúviel dancing in the forest, is the son of an outcast, which makes Tinwelint, Tinúviel’s father, very skeptical of him, because he is the son of someone who was a thrall of Melkor. Could that thralldom have been passed on? How could Tinwelint possibly trust him to be around his daughter?

Tolkien eventually wanted to change the storyline slightly, but the changes had the same effect. Beren became a Man instead of a Gnome, but Thingol was prejudiced against Men for two reasons. The first was because Men are attracted to power, and they woke after Melkor had done his earlier horrible deeds, so many Men latched onto his passion and became followers of Morgoth, the Dark Lord.

To the Elves, this was as bad or worse than thralldom. In the Silmarillion, it took many acts of Men to get Elves to trust them, and even then, they trusted the individual but still held a healthy distrust of the race.

The second reason Thingol didn’t like Beren and Lúthien’s connection was that Beren was a Man and thus mortal. If he let Lúthien fall in love with a mortal man, she would only have pain to look forward to because even though Men at this time in the Legendarium lived for over a hundred years, Elves were immortal. What was Lúthien to do when Beren died? We see this echo in The Lord of the Rings with Elrond as he speaks to Arwen about loving Aragorn.

So in both books, Tinwelint/Thingol makes a deal with Beren.

“‘Why! wed my Tinúviel fairest of the maidens of the world, and become prince of the woodland Elves – ’tis but a little boon for a stranger to ask,’ quoth Tinwelint. ‘Haply I may with right ask somewhat in return. Nothing great shall it be, a token only of thy esteem. Bring me a Silmaril from the Crown of Melko, and that day Tinúviel weds thee, an she will (pg 13).'”

Tinwelint knows that he is sending Beren off to his death. In the Book of Lost Tales, not a single Elf had gone up against Melkor because they knew him to be too powerful. Knowing that Beren’s father was a Thrall of Melkor, Tinwelint was probably hoping that Beren would have some genetic predisposition to stay under Melkor’s arm.

Nonetheless, Beren accepted:

“This indeed did Beren know, and he guessed the meaning of their mocking smiles, and aflame with anger he cried: ‘Nay, but tis too small a gift to the father of so sweet a bride. Strange nonetheless seem to me the customs of the woodland Elves, like the rude laws of the folk of Men, that thou shouldest name the gift unoffered, yet lo! I Beren, a huntsman of the Noldoli, will fulfil thy small desire,’ and with that he burst from the hall while all stood astonished (pg 13-14).”

Beren was off to go and collect the Silmaril, even though he knew it was a setup, but Tinwelint didn’t realize that as soon as night would fall, Tinúviel would steal away in the night to follow her love.

Join me next week as we continue the Tale of Tinúviel!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Lineage of Tinúviel

“Lo now I will tell you the things that happened in the halls of Tinwelint after the arising of the Sun indeed but long ere the unforgotten Battle of Unnumbered Tears. And Melko had not completed his designs nor had he unveiled his full might and cruelty (pg 10).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we begin Tolkien’s premier work in earnest and dissect the differences between what is in The Book of Lost Tales and what would eventually come in The Silmarillion.

The opening quote of this essay introduces the story to the reader, setting the stage for the events to come, but then Tolkien takes a step back and talks of the Elves of Doriath (which were not called such in this early version).

“Two children had Tinwelint then, Dairon and Tinúviel, and Tinúviel was a maiden, and the most beautiful of all the maidens of the hidden Elves, and indeed few have been so fair, for her mother was a fay, a daughter of the Gods; but Dairon was then a boy strong and merry, and above all things he delighted to play upon a pipe of reeds or other woodland instruments, and he is named now among the three most magic players of the Elves… (pg 10).”

If you have read The Silmarillion, you will probably recognize Tinúviel, and also Dairon as close to a character who stuck around. Still, otherwise, the names of the rest of the characters are entirely different.

Starting with our Titular character, Tinúviel, we know she kept that name in The Silmarillion. It’s the name Beren gave her because it means Nightingale, and he called her that when he found her dancing and singing in the forest. Her name changed to Lúthien, but there is still enough of a thread that it’s easy to keep everything in order.

Next, we have Tinwelint, who gained many names in the future as Tolkien began to develop his languages. Tinwelint became Elwë Singollo, leader of the hosts of the Teleri Elves, along with his brother Olwë. When Elwë led his people from Cuiviénen to Beleriand (the Teleri were known as the Last-comers, or the Hindmost, because, well, they were the last to come to Beleriand of the Eldar), he settled in the forests of Doriath (Where Beren saw Lúthien dancing). He ruled there under his better-known name, Elu Thingol.

Gwendeling, his wife, was not mentioned in the above quote but was also known as Wendelin in the Book of Lost Tales. She is a fay who falls in love with Tinwelint, marries him, and has two children.

Gwendeling, in my opinion, is how Tolkien decided to make the shift for the Maiar because, through the development of the Lay of Lúthien, he understood that women should play a much more significant role than he had initially been written (probably because of the influence of Edith). Gwendeling needed to possess powers of influence, most notably creating the Girdle of Melian, a protective shield over Doriath.

Because of this more extensive influence, Tolkien changed her lineage, and she became a Maiar, along with all of the other “children of the Valar” or Fay who never had a specific history. Doing so enabled Tolkien to have the Maiar keep their power set while at the same time lessening the ability of the Valar to have children (because if they are immortal, what is to stop them from continuing to have children who could potentially mess with the timeline)?

So Gwendeling became Melian the Maiar but stayed wife to Eru Thingol. That enabled Tolkien to make Lúthien a more robust character because she is the daughter of a demi-god and an immortal, but it left him in a strange quandary. In the book of lost tales, Tinúviel had a brother Dairon, and if he were to remain, he would also have to be a little more potent than the other Eldar because of his mother’s blood.

Dairon in the Book of Lost Tales is very talented, but one of those kids without any drive, as we see from the quote above. What he did possess, however, was an uncanny ability for music. He was considered the third-best “magic player” in the land, behind Tinfang Warble and Ivárë. You might remember Tinfang Warble from The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, because he was the half-fay flutist in the Cottage of Lost Play.

To adjust this inequity of power, Tolkien decided to slightly change Dairon’s name to Daeron, who then became one of the greatest minstrels of all time; in fact, the only being to come close to him was Maglor, Fëanor’s son (who is probably the later iteration of Ivárë). However, he became just a regular Eldar, no longer Thingol and Melian’s son, but rather a trusted loremaster of Thingol. More importantly, he was deeply in love with Lúthien.

This adjustment makes for a slightly better tale because rather than her brother betraying her excursion after Beren, it is an unrequited lover looking out for her best interest when he betrays her trust and tells Thingol that she went after Beren.

That takes care of the family, but what then of Beren? The most provocative change that Tolkien made here is that in the Book of Lost Tales, part two, is that Beren is an elf, not a man.

I believe he did this for several reasons, but two of them stand out to me the most:

- Men were not awake yet. At the end of the Book of Lost Tales, part 1, we see that they are children lounging by the Waters of Awakening. Tolkien didn’t spend time developing them like in The Silmarillion. Plus, The Silmarillion is considered the history of the Elves, even though much more happens there, so it makes sense that Beren would be an elf early on.

- Changing Beren to a Man adjusts the Legendarium in a fun and dynamic way. Now we have the dichotomy of the difference between Elves and Men and what that would mean for them to come together, fall in love, and potentially have children. The remainder of the time in Middle-earth stems from this relationship, so Tolkien needed to adjust it.

That was a lot to break down in just the opening pages! Join me next week as we dive into the story proper!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1; Gilfanon’s Tale

“Suddenly afar off down the dark woods that lay above the valley’s bottom a nightingale sang, and others answered palely afar off, and Nuin well-neigh swooned at the loveliness of that dreaming place, and he knew that he had trespassed upon Murmenalda or the “Vale of Sleep”, where it is ever the time of first quiet dark beneath young stars, and no wind blows.

Now did Nuin descend deeper into the vale, treading softly by reason of some unknown wonder that possessed him, and lo, beneath the trees he saw the warm dusk full of sleeping forms, and some were twined each in the other’s arms, and some lay sleeping gently all alone, and Nuin stood and marvelled, scarce breathing (pg 232-233).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we conclude The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, discussing symbolism and creative editing.

This chapter is more of Christopher’s musings on how his father was positioning the editing of the book rather than the tale itself. Gilfanon only has a few pages, and the rest of his story remains unfinished. In a more accurate sense, this is an early iteration of the chapter in the Silmarillion “Of Men.”

The origin of Men for Tolkien was a difficult thing to tackle. Christopher tells us that there were four different iterations throughout the process of coming up with the concept. Tolkien ended up significantly cutting down the chapter to be what it eventually became, which was relatively uninspired and just about as long as Gilfanon’s tale. One has to wonder if the weight of the linchpin of his mythology was so great that the chapter says, “They wake,” and then moves on.

Gilfanon’s tale tells of one of the Dark Elves of Palisor, Nuin. Nuin is restless and curious about the world, so he ventures out to experience it and comes across a meadow that holds The Waters of Awakening and humans sleeping near it (described in the quote above).

Nuin then heads back home and tells a great wizard who ruled his people about the humans sleeping by the waters and “Then did Tû fall into fear of Manwë, nay even of Ilúvatar the Lord of All (pg 233).” because of this fear he turned to Morgoth, and learned deeper and darker magic from him.

From what Christopher tells us, each version of the story Tolkien worked on evolved, and eventually, Tû, the Wizard, was cut from the Silmarillion. Tolkien cut nearly all mention of the elves who went to Morgoth’s side from the main context. There are only a few mentions of thralls throughout the main storyline.

One has to wonder if this was Tolkien’s decision that the Elves themselves shouldn’t turn to the “dark side.” Even though the Noldor did some heinous things in Swan Haven, they ultimately did it out of a hatred that burned so deep for Morgoth’s blood that they wouldn’t let anyone stand in their way.

The inclusion of Tû, even if he is more of a fay creature than Elvish, creates issues with Tolkien’s history. So he took the name Tû out of the book to keep the Elvish lines as “pure” as possible, but the character of Tû is still in the book, AND I believe he plays a much larger part.

Remember that Tû is described as a fay wizard, and the only wizards in the history of Eä were the Istari (of which Saruman and Gandalf were a part). The Istari were Maiar, otherwise known as lesser Valar. In general, they were servants to the Valar (in The Book of Lost Tales, many of them were the children of the Valar) and aided in bringing the will of Ilúvatar into being.

The Istari were sent to Middle-earth in the Second Age to assist the people of that land in their fight against Sauron. They could turn into a mist and travel vast distances to reach their destination – something Sauron did after the Drowning of Númenor.

So this early Wizard trained in the dark arts by Morgoth must be an earlier version of Sauron himself. Sauron, after all, assisted the Elves in the creation of the Rings of Power, was known to be a wizard himself, and eventually picked up Morgoth’s mantle when the Dark Lord was locked behind the Door of Night.

The other exciting portion of the quote I’d like to discuss before closing thoughts is the mention of Nightingales and the Coming of Man in the opening quote.

Nightingales generally have a long history of symbolism, more specifically revolving around creativity, nature’s purity, or a muse. All of these aspects center around virtue and goodness.

Tolkien is using the nightingale song to indicate a more artistic and virtuous age because when Nuin followed the song, he came across the sleeping children by the Waters of Awakening.

Tolkien’s tale is ultimately (as we’ve covered many, many times) about Man (read that as Humans), so everything we have read thus far has been pre-history, which is also why Christopher separated The Book of Lost Tales into a part 1 and a part 2. Part 1 is about how the world became what it was. Now that we have humans, Part 2 is about the rest of the first age and carries what Christopher calls “all the best stories.”

So the nightingale indicates to the fay and the Eldar (Gnomes in The Book of Lost Tales) that there will be a shift in the world, and they will no longer be the focal point. This also spooks Nuin because, at the moment, by the Waters, he sees that his time will come to a close eventually, even though he’s immortal. The world was not built for him but for the new creatures just now waking into the world.

Join me next week as we have some final thoughts on The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, before jumping into The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, the week after!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Tale of the Sun and the Moon

“Then there was silence that Manwë might speak, and he said: ‘Behold O my people, a time of darkness has come upon us, and yet I have it in mind that this is not without the desire of Ilúvatar. For the Gods had well-nigh forgot the world that lies without expectant of better days, and of Men, Ilúvatar’s younger sons that soon must come. Now therefore are teh Trees withered that so filled our land with loveliness and our hearts with mirth that wider desires came not into them, and so behold, we must turn now our thoughts to new devices whereby light may be shed upon both the world without and Valinor within (pg 181).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we get back into Tolkien’s religious background as we cover the Tale of the Moon and the Sun.

We’ve come to a point in the story where Melkor has killed the Trees of Valinor, and the Noldor killed many of their kin to steal ships to chase Melkor to Middle Earth.

The Vala faced the difficulty of what they should do. Melkor had left Valinor in darkness, and the trees were dead. What should their first action be? To go after Melkor and imprison him again, or try to figure out how to bring light back to Valinor.

The Spoke to Sorontur (who later became Thorondor), the King of Manwë’s eagles, and asked him to spy on Morgoth.

“…he tells how Melko is now broken into the world and many evil spirits are gathered to him: ‘but,’ quoth he, ‘methinks never more will Utumna open unto him, and already is he busy making himself new dwellings in that region of the North where stand the Iron Mountains very high and terrible to see (pg 176).'”

So the Valar doesn’t have to worry about Melkor for the time being because he will be spending all his time trying to make a home for himself. After hearing the Eagle’s report, it’s their opinion that Melkor will not be returning to Valinor, so he is now the Noldor’s problem, which they deserve because of the transgressions they laid on their fellow kin.

So that brings them back to their other issue. How do they deal with the loss of the light of Valinor? They decide that they must build a great ship and use the remainder of the light of the Trees, and this new ship can be like the stars, but it will travel the sky and light Valinor once again.

The prospect of the ship is exciting because it calls to mind the Greek God Helios, who rode a great chariot across the sky, and that is how the sun was to rise and set. Remember that Tolkien’s ultimate work was to create new mythos and mythology for England because Spencer’s work was sub-par (to Tolkien). This ship across the sky, built by gods, was a way that he could make things unique enough to fit within his landscape of fantasy. He even had a reason for the ship to rise and set:

“Now Manwë designed the course of the ship of light to be between the East and West, for Melko held the North and Ungweliant the South, whereas in the West was Valinor and the blessed realms, and in the East great regions of dark lands that craved for light (pg 182).”

But while they built this idea, he collected mythology from other areas and brought it into his ethos. Eventually, the ship was a failure. The downfall shows that Tolkien believed he was writing the ultimate mythology because the portion he took from another culture ultimately failed.

The Vala went back to Yavanna, who had created the Trees in the first place, but she had run through the energy needed. She poured everything she had into the trees, but it was Vána (another Valar who only appears in these early iterations) who made the most significant difference:

“Now was the time of faintest hope and darkness most profound fallen on Valinor that was ever yet; and still did Vána weep, and she twined her golden hair about the bole of Laurelin and her tears dropped softly at its roots; and even where her first tears fell a shoot sprang from Laurelin, and it budded, and the buds were all of gold, and there came light therefrom like a ray of sunlight beneath a cloud (pg 184).”

The tears of love brought Laurelin back to life enough to get those sprouts. “One flower there was however greater than the others, more shining, and more richly golden, and it swayed to the winds but fell not; and it grew, and as it grew of it’s own radient warmth it fructified (pg 185).”

The fruit that grew from the tree of Laurelin grew from tears, death, and rebirth. This fruit was, for Tolkien, his introduction to the Christian ideal of the Fruit of Knowledge. Still, instead of one of the Valar eating it and causing sin, the sin has already been created. The knowledge of death, destruction, jealousy, and Hubris has already taken hold of the peoples of Middle-earth because of Tolkien’s fallen Angel Melkor.

“Even as they dropped to earth the fruit waxed wonderfully, for all the sap and radience of the dying Tree were in it, and the juices of that fruit were like quivering flames of amber and of red and its pips like shining gold, but it’s rind was of a perfect lucency smooth as a glass whose nature is transfused with gold and therethrough the moving of its juices could be seen within like throbbing furnace-fires (pg 185).”

The Valar had found the fruit of knowledge that could shine the light on the land and destroy the darkness. The fruit knew what came before, and its sole meaning was to shine the morning so that others didn’t have to carry the burden of its dark understanding.

Join me next week as we complete the Tale of the Sun and the Moon.

Blind Watch: The Rings of Power; Episode 8, Alloyed