Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2, Túrin’s Second Tragedy

“In that time was Túrin’s hair touched with grey, despite his few years. Long time however did Túruin and the Noldo journey together, and by reason of the magic of that lamp fared by night and hid by day and were lost in the hills, and the Orcs found them not.”

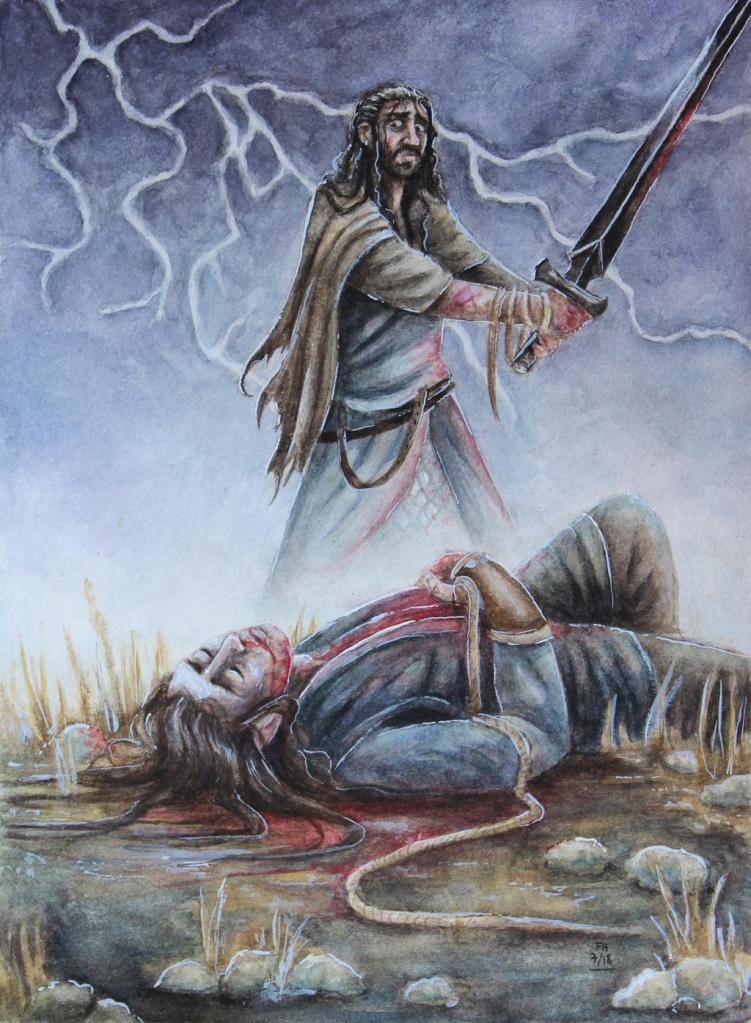

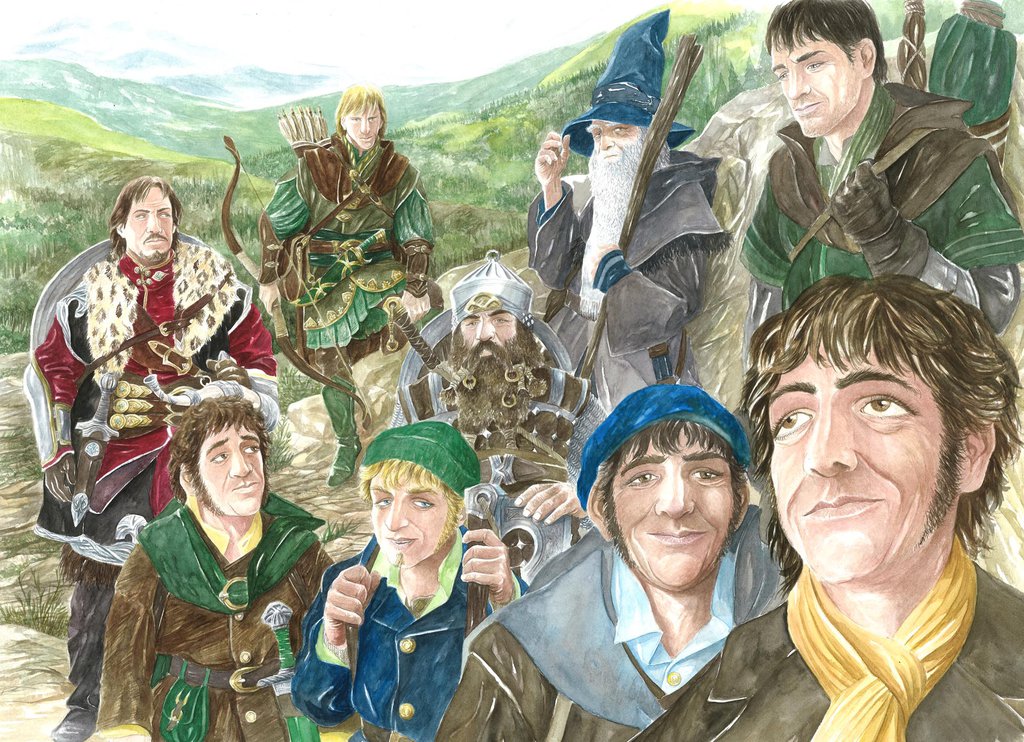

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we cover Turambar’s second tragedy and discover his life and vision of himself as an outlaw and what that means for him moving into the rest of his story.

We left off last week with Túrin leaving Doriath and heading off into the wilds, where he met up with Beleg, an Eldar of the court of Tinwelint. Tolkien spent time developing Beleg later in the Silmarillion (probably to give Túrin’s actions more significant stakes). Still, in this version, he becomes a traveling companion and a Captain against Melko.

The two range in the wilds and hunt orcs and other foul creatures of the darkness. For many of these hunters, the goal was to lessen Melko’s hold on the world and make it a little more accessible for everyday people to wander. For Túrin, it was about killing these foul creatures, which showed his true nature.

In the Silmarillion, Beleg played the role of the conscious. Túrin ran off with the outlaws, and Beleg was sent after him to be a protector and to remind him of his upbringing. There is even a sentiment that Beleg should bring Túrin back if possible, and he is given the Dragon Helm of Dor-lómin to give to Túrin to show that even if he doesn’t come back, they wish him to be safe.

In The Book of Lost Tales, Beleg is already out in the wilds, and Túrin joins him. Their bond is strong, and they become like brothers out in the wilds hunting the creatures of Melko. But living that life can only last so long before life catches up with you.

It wasn’t long before they came across “a host of Orcs who outnumbered them three times. All were there slain save Túrin and Beleg, and Beleg escaped with wounds, but Túrin was overborne and bound, for such was the will of Melko that he be brought to him alive (pg 76).”

Túrin stayed a captive of the Orcs for some time. They abused and beat him to within an inch of his life, and “was Túrin dragged now many an evil league in sore distress (Pg77).”

During this time, Melko unleashed “Orcs and dragons and evil fays (pg 77)” upon the people of Hithlum to either take them as thralls or kill them as retribution for the outlaw brigade led by Túrin.

Meanwhile, Beleg wandered in the wilds, killing evil creatures and looking for his lost compatriots. He did so until he came upon an encampment of Orcs and saw that in this camp was a restrained Túrin. Thus, we get Túrin’s second great tragedy:

“but Beleg fetched his sword and would cut his bonds forthwith. The bonds about his wrists he severed first and was cutting those upon the ankles when blundering in the dark he pricked Túrin’s foot deeply, and Túrin awoke in fear. Now seeing a form bend over him in the gloom sword in hand and feeling the smart of his foot he thought it was one of the Orcs come to slay him or torment him – and this they did often, cutting him with knives or hurting him with spears; but now Túrin feeling his hand free lept up and flung all his weight suddenly upon Beleg, who fell and was half-crushed, lying speechless on the ground; but Túrin at the same time seized the sword and struck it through Beleg’s throat…(pg 80).”

Túrin felt like an outcast because he was a man living with Elves and his accidental killing of Orgof, but now, with the murder of Beleg, he has become a full-fledged Outlaw. It is not in his nature to return to Tinwelint and confess his wrongdoing, even if the Elven King would forgive and pardon him. Túrin internalizes his struggles and becomes depressed in the way only a Man (human) can.

Tolkien wrote the races of Middle-earth (I have still not seen a mention of Beleriand yet in The Book of Lost Tales) to have all range of emotion, but Elves never really seem to get maudlin like Men do. Their immortality gives them a view of the world that eliminates general depression, but Man’s mortality appears to encourage it. We see that slightly in Beren, but it is full front and center for Túrin. His entire story has a sort of “woe is me” feel – even though it’s his fault that these things happen to him. Túrin lives his life in a state of impetuousness, which leads to desperation. In that desperation, he takes events as they come to him without giving them a second thought.

So when he escapes the Orcs with the Elf Flinding, who incidentally is also a bit of an outcast for his actions, they come across a group of wandering Men called the Rodothlim who live in caves.

The Rodothlim “made them prisoners and drew them within their rocky halls, and they were led before the cheif, Orodreth (pg 82).”

Here in the caves of the Rodothlim (which I believe must be a precursor to the Rohirrim), Túrin met Failivrin, a maiden of those people. She quickly met the dreary man and “wondered often at his gloom and sadness, pondering the sadness in his breast (pg 82).”

Despite her affection for him, Túrin couldn’t leave his past behind, “but he deemed himself an outlawed man and one burdened with a heavy doom of ill (pg 82-83).”

The caves of the Rodothlim had a strange effect on Túrin. Those people survived in the wilds because their caves gave them a veil from Melko’s agents and eyes, which gave Túrin a respite from having to face those monsters directly – but it also gave him time to think, dream, and replay his past life. In those caves of safety, Túrin made a mental shift and knew he could never be accepted in any typical setting. He was born an outlaw, and his fate was exclusively intertwined with that life. He decided to lean into the outlaw life, which was just one more bad decision in a long list of bad choices.

Join me next week as we continue on Túrin’s tragic journey!

Blind Read Through: J.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Link of Tinúviel

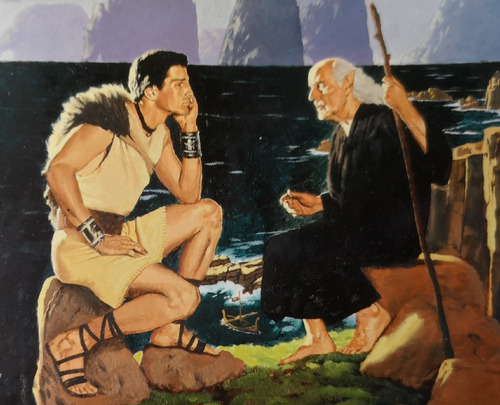

“Then there was eagerness alight, and Eriol told them of his wanderings about the western havens, of the comrades he made and the ports he knew, of how he was wrecked upon far western islands until at last upon one lonely one he came on an ancient sailor who gave him shelter, and over a fire within his lonely cabin told him strange tales of things beyond the Western Seas, of the Magic Isles and that most lonely one that lay beyond. Long ago had he once sighted it shining afar off, and after had he sought it many a day in vain (pg 5).“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we begin The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, with the story of Middle-earth, which was closest to Tolkien’s heart.

This story is the earliest written tale in the Legendarium, even earlier than the tales of Ilúvatar and the Valar. Tolkien wrote the first manuscript in 1917 amid the Great War, and I have to imagine that he did so because he wanted a release from the horrors of the war happening around him.

Tolkien wrote the Tale of Tinúviel about his wife, Edith Tolkien, and it is both a beautiful homage and the seed from which all Middle-earth blossoms.

Those who know the story of Beren and Lúthien realize it is the tale of a man who falls in love with the most beautiful elven maid alive. Not only is she beautiful and sings like a nightingale, but she is a strong woman, a warrior, and a leader. Tolkien has been very forthright with the fact that Lúthien is, in fact, Edith, and the story of Beren seeing Lúthien singing and dancing in the forest was a call back to their walks in the dense woods of England when they first met.

This also means that the world of Middle-earth that Tolkien built would not be possible without Edith. Everything that happens in the Legendarium stems from this first origin (though doubtless there are poems written before this story, this was the first instance Tolkien wrote a new world through the lens of prose instead of poetry). Lord of the Rings even stems from this story. It echoes in Aragorn and Arwen, the Third Age’s version of Beren and Lúthien. There is even a passage in The Lord of the Rings compares Aragorn and Arwen to Beren and Lúthien.

This love story was at the core of everything that Tolkien wrote, and he built the greater Legendarium to support the story of his love for his wife. Though the tale grew beyond this conception, it remains the core of everything in Middle-earth.

Reviewing this tale will take multiple weeks, so to kick it off, I’d like to start with Eriol’s story and the link between where we left off in The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Also with where this book begins with The Tale of Tinúviel.

The tome takes up days after the events of Book of Lost Tales, part 1, with Eriol wandering in Kortirion, learning Elvish language and lore. One day as he is talking with a young girl and in a role reversal, she asks him for a tale:

“‘What tale should I tell, O Vëanne?’ said he, and she, clambering upon his knee, said : ‘A tale of Men and of childrren in the Great Lands, or of thy home – and didst thou have a garden there such as we, where poppies grew and pansies like those that grow in my corner by the Arbour of the Thrushes?'”

It may seem strange to call out this quote, but I do so because the passage ends here. Tolkien must have had the idea that Eriol would tell the history of Men, whereas the people of the Cottage of Lost Play would tell the story of the early times and the Elves.

Christopher gives a few different iterations of this interaction. Still, in every one of them, the story gets taken out of Eriol’s mouth as Vëanne interrupts him and begins the Lay of Lúthien (I.E., The Tale of Tinúviel).

I wonder if the intent was for Eriol to have his section of the book (which never actually happened) because Tolkien spends time here to set it up:

“‘I lived there but a while, and not after I was grown to be a boy. My father came of a coastward folk, and the love of the sea that I had never seen was in my bones, and my father whetted my desire, for he told me tales that his father had told him before (pg 5.)'”

The opening quote in this section talks about his “wanderings.” Before we get into the Tale of Tinúviel proper, there is also Eriol’s unwitting interaction with a Vala:

“‘For knowest thou not, O Eriol, that that ancient mariner beside the lonely sea was none other than Ulmo’s self, who appeareth not seldom thus to those voyagers whom he loves – yet he who has spoken with Ulmo must have many a tale to tell that will not be stale in the ears even of those that dwell here in Kortirion (Pg 7).'”

Eriol, to me, is a fascinating character because he has such a history, and he’s a mariner. If Tolkien created some stories from Eriol’s perspective, we might be able to see Middle-earth from a slightly different perspective, that of a sea-faring folk.

We know that all the history had come before this discussion. All of the first age (The Silmarillion) and the Second age (Akallabeth), and even the Third Age (The Lord of the Rings) came before Eriol’s time. So we can think of this soft opening in Kortirion as a Fourth Age, where Men (read Humans) run the world, the Elves have retreated to hidden Valinor, and much of the pain from the Dark Lord has disappeared, or at very least forgotten, from the world.

Join me next week as we start The Tale of Tinúviel!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, Final Thoughts

“Melko shalt see that no theme can be played save it come in the end of Ilúvatar’s self, nor can any alter the music in Ilúvatar’s despite. He that attempts this finds himself in the end but aiding me in devising a thing of still greater grandeur and more complex wonder:–for lo! through Melko have terror as fire, and sorrow like dark waters, wrath like thunder, and evil as far from the light as the depths of the uttermost of the dark places, come into the design that I laid before you. Through him has pain and misery been made in the clash of overwhelming musics; and with confusion of sound have cruelty, and ravening, and darkness, loathly mire and all putrescence of thought or thing, foul mists and violent flame, cold without mercy, been born, and Death without hope. Yet is this through him and not by him; and he shall see, and ye all likewise, and even shall those beings, who must now dwell among his evil and endure through Melko misery and sorrow, terror and wickedness, declare in the end that it redoundeth only to my great glory, and doth but make the theme more worth the hearing, life more worth the living, and the World so much the more wonderful and marvellous, that of all the deeds of Ilúvatar it shall be called his mightiest and his loveliest.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we recap The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, and in doing so, speak about the more fantastic aspect of Middle-earth and Tolkien’s intention.

The Book of Lost Tales is an amalgam of Tolkien’s work throughout his life. Christopher has included some of his father’s earliest poems, scraps of notes stuck into notebooks, various illustrations, and books and books of re-writes to show the thought and care Tolkien put into the work.

John wanted to tell a fantastic story that would give people meaning. He wanted a new fairy tale that would anchor into our world and give people wonder and hope (and perhaps even give reasoning for things like The Great War).

Many critics have said that The Lord of the Rings is an allegory to Tolkien’s time in the war, and if you only read the book itself, it is easy to understand why. Tolkien, however, hated allegory and had often stated that he pulled inspiration from his time in the war, but there was no allegory there. That can be hard to swallow, especially when his fellow Inkling (a society of writers who met to critique and edit each other’s work), C.S. Lewis, thought allegory one of the greatest literary techniques.

The story produced in The Lord of the Rings was a work of love developed over many decades, but to create a work so deep and well established Tolkien wanted a robust history of the world, that history is what eventually became The Silmarillion.

But Tolkien, like many authors, wanted the history of the world to be a story in and of itself, so in the earlier iterations, we get the tale of Eriol, who in turn is told the story behind The Silmarillion.

The problem Tolkien ran into, however, was that history is difficult to tell in a story format. There are fantasies, records, and fairy tales told in the Silmarillion, but they come late in the book and feel more like what he would eventually write in The Lord of the Rings. The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, is Eriol learning instead about the Valar and how the Eldar (Gnomes in this earlier version) came into being. However, even in these earlier versions, we still need to catch minor differences with how Tolkien later decided to frame everything.

Facts, like the Maiar being the children of the Valar, the Eldar being Gnomes, and the sparse inclusion of Fëanor are stark differences to how the story eventually played out, and what is great about reading through this book was being able to read Christopher’s analysis (Tolkien’s son and editor) of where Tolkien tried to take the story, and where he decided to end up. This process is the magic of reading The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Part 2, I’m sure, will have just as many quirks, but part 2 is where the stories that built the history of Mankind came into being. Stories like the Lays of Lúthien, the Tale of Túrin Turambar, and the Fall of Gondolin all take place in the second half of these histories. These tales inform our characters in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Beyond The Silmarillion, there is minimal mention of the Valar or Ilúvatar.

In Christopher’s sentiment, the first book is less interesting because it’s about the development of the world itself and not necessarily about the people; thus, it’s harder to give stakes because we know what will eventually happen.

Knowing all this, Ilúvatar is the most provocative being or concept in Tolkien’s oeuvre. Ilúvatar is God for this World (even though the Valar intermittently are called gods, Tolkien later stripped them of that title for The Silmarillion).

The quote to start this essay is a perfect example of the fallibility of gods in general. Tolkien was deeply religious, and I’m sure he wrote Ilúvatar to be Middle-earth’s Yahweh and much of the struggle and philosophy in Middle-earth is how to accept or deal with the concept of Death. Death is a “gift” given to Man when they are born, so they might make life more meaningful. Death was not a concept until Morgoth sang its theme into existence.

This path makes Melkor the most tragic character in the pre-history of Middle-earth because, as we see from the opening quote, he has no choice. Ilúvatar, as the master creator, knew every theme he wanted to put into the world, and Death, hate, and suffering would be part of existence.

Iluvatar created each Vala to inform specific parts of his themes, but themes were all they were, meaning that the Valar had free will over what theme they were given. Iluvatar created Melkor to suffer. He created him to be a Dark Lord because he knew that without a Dark Lord making people work for their freedom, they would take their lives for granted.

Tolkien didn’t write Allegory; he wrote philosophy. Death is a gift because we cannot appreciate light without darkness. We cannot fully appreciate life without death.

Come join me next week as we begin our foray into “The Book of Lost Tales, part 2,” the second book of the Histories of Middle-earth!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Darkening of Valinor

“Now Melko having despoiled the Noldoli and brought sorrow and confusion into the realm of Valinor through less of that hoard than aforetime, having now conceived a darker and deeper plan of aggrandisement; therefore seeing the lust of Ungwë’s eyes he offers her all that hoard, saving only the three Silmarils, if she will abet him in his new design (pg 152).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we’re going to dive into the philosophy of Tolkien’s world through the events of The Darkening of Valinor.

We’ve discussed it before, but Tolkien relied heavily on his Christian background while creating this mythology. He wanted something new and unique for England, and as we know, mythologies are all origin stories.

The people of Middle-earth (Elves, Men, Dwarves, etc.) are all iterations of our evolution, and it shows from the beginning of The Book of Lost Tales that Tolkien intended for Middle-earth to be a precursor to Earth (he even calls it Eä in the Silmarillion).

Because this is mythology, Tolkien brings his version of the afterlife and the angels he introduces to the world. Melkor, who is Tolkien’s version of Satan, is ostracized for stealing the Eldar gems and Silmarils. Cast out of Heaven as it were:

“Now these great advocates moved the council with their words, so that in the end it is Manwë’s doom that word he sent back to Melko rejecting him and his words and outlawing him and all his followers from Valinor for ever (pg 148).”

But it was still during this period that Melkor was mischievous, but he had not transitioned to evil yet, even after being cast out of Valinor. So instead, he spent his time trying to create chaos using his subversive words:

“In sooth it is a matter for great wonder, the subtle cunning of Melko – for in those wild words who shall say that there lurked not a sting of the minutest truth, nor fail to marvel seeing the very words of Melko pouring from Fëanor his foe, who knew not nor remembered whence was the fountain of these thoughts; yet perchance the [?outmost] origin of these sad things was before Melko himself, and such things must be – and the mystery of the jealousy of Elves and Men is an unsolved riddle, one of the sorrows at the world’s dim roots (pg 151).”

The great deceiver has been created out of jealousy and anger for these beings of Middle-earth, believing that they were given more than their fair share and his own acts were ruined from the beginning of the Music of the Ainur.

But what did the Elves do? Was there anything they received that made anything Melkor did excusable?

“And at the same hour riders were sent to Kôr and to Sirnúmen summoning the Elves, for it was guessed that this matter touched them near (pg 147).”

It was nothing that they did, but the fact that the Valar treated them as equals to the Valar and Melkor’s slights against them weren’t considered pranks he felt they were, so his anger grew.

They were also allowed to be near their loved ones even after death. Elves were given the gift of immortality but can still be killed by disease or blade. But where do their spirits go when they die? Remember that this is a Christian-centric mythology, so Tolkien built an afterlife.

Called Vê after the Valar who created it, the afterlife on Middle-earth is contained within and around Valinor. This early conception (nearly cut entirely from The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings) was that Vê was a separate area of Valinor, slightly above and below it but still present, almost like a spirit world that contained the consciousness of the dead.

This region was all about, and the Eldar cannot commune with their deceased, but they continue to live close to them, and their spirit remains in Valinor.

“Silpion is gleaming in that hour, and ere it wanes the first lament for the dead that was heard in Valinor rises from that rocky vale, for Fëanor laments the death of Bruithwir; and many Gnomes beside find that the spirits of their dead have winged their way to Vê (pg 146).”

Melkor is jealous that the Elves can be so close to their dead ancestors, but he also doesn’t fully comprehend what being dead means because he is a Valar and eternal. He sees these beings going off to a different portion of Valinor and is upset because he thought he found a way to create distress amongst them by killing one of them. He doesn’t realize that he made a fire in the Eldar that would never wane.

“‘Yea, but who shall give us back the joyous heart without which works of lovliness and magic cannot be? – and Bruithwir is dead, and my heart also (pg 149).'”

Melkor schemed and stewed in his frustration and anger, feeling that even with his theft and his killing of Fëanor’s father, the first death of an Eldar (whom Tolkien was still calling Gnomes in this early version), there was nothing he could do to prove his worth, so his worth turned to evil. His music was dissonant and didn’t follow the themes of the other Valar, and he was looked down upon for that and cast aside. He pulled pranks that caused the other Valar to imprison him. All the while, his anger, and distrust grew until he did the ultimate act, which caused his to turn to true evil: He partnered with Ungoliant (the giant spider queen and mother of Shelob) and killed Silpion and Laurelin, the Trees which gave light to Valinor.

“Thus was it that unmarked Melko and the Spider of Night reached the roots of Laurelin, and Melko summoning his godlike might thrust a sword into its beauteous stock, and the firey radiance that spouted forth assuredly had consumed him even as it did his sword, had not Gloomweaver (Ungoliant) cast herself down and lapped it thirstily, plying even her lips to the wound in the tree’s bark and sucking away it’s life and strength (pg 153).”

Melkor had finally become evil. He had turned against the Valar and what brought the world light and gave that power to evil creatures.

The Valar and Eldar cried out against Melkor for being cruel, but the tragedy of Melkor’s story was that he never had a choice.

Early in the mythology of this world, Tolkien tells us that Ilúvatar had a theme and a story for eternity, which the Valar were not privy to. Instead, they thought their music and their acts were meant to create only beauty and love.

Ilúvatar, however, knew that to have true meaning, there must be pain, conflict, and evil. Otherwise, all the world’s good would disappear and become mundane. So Ilúvatar created Melkor, knowing what he was going to become. He made Melkor evil in the world.

Melkor was born to suffer. Melkor was born never to know love. Melkor was created to become a creature that others could be tricked into feeling sorry for, and thus trade the light of the Valar for the Darkness of the Dark Lord.

Join me next week as we cover “The Flight off the Noldoli!”

Blind Watch: The Rings of Power; Episode 6, Udûn

“My children, we have endured much. We cast off out shackles. Crossed mountain, field, frost, and fallow, till out feet bloodied the dirt. From Ered Mithrin to the Ephel Arnrn, we have endured. Yet tonight, one more trial awaits us. Our enemy may be weak, their numbers meager…yet before this night is through, some of us will fall. But for the first time, you do so not as unnamed slaves in far-away lands, but as brothers. As brothers and sisters in our home! This is the night we reach out the iron hand of the Uruk…and close our fist around these lands.“

Welcome back to another Blind Watch! This week we cover Episode six of The Rings of Power, Undûn. The episode is fast-paced and fun to watch, but there is very little content in this episode based on the core material.

This episode focused solely on the southland’s battle for survival against the orcish horde and showed the treachery of men wooed by Sauron’s power delicately and subtly. But it also shows how people can hold onto hope nearly as well as Peter Jackson did in “The Lord of the Rings.”

We start the episode with the Orcs storming the tower. The Southlanders have fled, and Arondir stays behind to lay traps for the scourge.

It’s here, Waldreg, the human who betrayed his kinsmen and ran off to join Adar shows his concern for the Orc Captain, but there is something strange about his motivations. He follows Adar fervently, but we don’t know why he does this. Earlier in the season, he shows the mark on his arm. He gained that mark from using the hilt which becomes a sword from his blood, but where did he get the hilt? Why did he lose it, and where did Theo get it? Was Waldreg previously a soldier in Sauron’s armies and used the blood sword? Has he been a spy all these years? Unfortunately, they haven’t given us enough to make a proper conclusion.

We then transition to Galadriel and the Númenóreans on the ship on their way to help the Southlands. They show a bit of interaction between Galadriel and Isildur, where Isildur says, “I was just trying to get away. As far as I could from that place.“

Isildur wanting to leave Númenor is actual history, but it takes place before the events in the show. Isildur was trying to get away from Númenor, but it wasn’t until after he was already a hero for taking the fruit of Nimloth and saving the tree’s offspring from the evil of Sauron and Pharazôn. Isildur was gravely injured because of his heroism and “went out by night and did a deed for which he was afterwards renowned.” The problem I have, is that he has already left Númenor, so if the showrunners decide this event is to be his redeeming deed, then they need to find some way to bring him back to Númenor before the great flood.

The remainder of the episode takes place in the Southlands. The Humans all retreat to the town and set up an ambush for the Orc army, who attacks them at night. They successfully attack and push back the Orcs but find that most of the beings they killed were, in fact, their fellow humans who left town to join Adar. These humans are just in disguise, made up to look like Orcs.

Once this realization happens, the actual garrison of Orcs attacks the humans, only to be pushed back again by the Númenóreans, who have the best possible timing.

If you weren’t paying attention, however, you might miss Adar saying, “Waldreg, I have a task for you.“

The Númenóreans go onto a glorious victory, at least it seems. We see Waldreg finds the broken hilt, and he places it in some lock which activates a flood.

The flood goes all the way through to what I can only imagine is Mount Doom, where Sauron forged the One Ring. Then, the water creates a chain reaction which causes a significant eruption.

You might wonder why the episode is called Udûn. It’s the Elvish word for Hell or Dark Pit. The tunnels that the Orcs had been tunneling weren’t just searching or trying to seek something. It was that because they wanted the hilt, but they were also making tunnels so the water released by the hilt key would create a chain reaction that would cause hell on earth for the humans. Fireballs and magma fill the ground, and it’s a more extensive form of destruction that hasn’t been seen since Ancalagon the Black crushed mountain tops underneath its claws (an enormous dragon ever to live in Middle-earth and servant to Morgoth). What is even more devious is that Udûn is Sindarin Elvish, which proves the point that these Orcs were indeed transitioned from Elves to these creates because of Sauron’s corruption. Udûn is also the name of the region just beyond the black gate of Mordor. Coincidence?

So there is just one question remaining. Arondir tries to destroy the hilt key earlier in the episode, but the hammer he uses breaks instead.

What can this blade be but Gurthang, the sword of Turin Turambar? Turin is a hero of legend in the first age, surrounded by bad luck. His sword was Gurthang, which he used to slay many powerful creatures, including Glaurung, Morgoth’s Dragon Captain. Unfortunately, Turin killed himself once he realized he was married to his sister (who killed herself just before he did the deed), and the blade broke asunder after that happened, which is the only way the sword could be broken. Gurthang was a sentient sword, and there is a prophecy (interesting prospect in a show heavily leading on the sign laden Palatirí) where Turin will use Gurthang in the Final Battle to kill Morgoth for infinity.

I could see the showrunners using Gurthang as a key to release Sauron from the trappings of his spirit form and return him to his mortal form.

This is the blade, after all, that feeds off blood and remembers its kills.

So despite the lack of history in the last few episodes, I am excited about where this is going because if I’m right about this sword being Gurthang, it opens up whole new worlds of history to be exposed. There will be considerably more people who have never read The Silmarillion exposed to its lush history.

So join me next week and experience some of that history as we continue with “Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age!”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of The Rings of Power and the Third Age, part 1

“But Sauron gathered into his hands all the remaining Rings of Power; and he dealt them out to the other peoples of Middle-earth, hoping thus to bring under his sway all those that desired secret power beyond the measure of their kind. Seven rings he gave to the Dwarves; but to Men he gave nine, for Men proved in this matter as in others the readiest to his will.“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we start the last chapter of The Silmarillion and learn how the events of The Lord of the Rings came to be.

Tolkien begins this chapter by describing Sauron himself. Sauron was a Maia, one of the servants of the Valar, and just a half step down in power from them. Melkor seduced Sauron with his power and led him to serve the Dark Lord, but when Melkor was defeated, he begged forgiveness. Then, when it was clear that no quarter would come, he “hid himself in Middle-earth; and he fell back into evil, for the bonds that Morgoth had laid upon him were very strong.”

I contend that Sauron is much more evil than Morgoth (Melkor) because Melkor’s goal wasn’t ultimate power; instead, his story falls much more in line with Lucifer Lightbringer, who was an angel but pride made him feel slighted, which created his fall. Sauron chose evil from the beginning. There was never anything in him that tried to be or do good; his entire existence was about deception and power.

This whole chapter is basically about Sauron and his influence on how he corrupted the Rings of Power to gain control over the people of Middle-earth and what those people did to fight against him.

Tolkien tells us the land beneath Ossiriand on the eastern side of what was once Beleriand was re-formed by the surging of rivers and shifting of the ground. The region is now called Lindon, where many Elves settled to live.

Those that didn’t live there posted up in a region to the west of Khazad-dûm named Eregion. “In Eregion the craftsmen of the Gwaith-i-Mírdain, the People of the Jewel-smiths, surpassed in cunning all that have ever wrought, save only Fëanor himself; and indeed greatest in skill among them was Celebrimbor, son of Curufin, who was estranged from his father and remained in Nargothrond when Celegorm and Curufin were driven forth, as is told in the Quenta Silmarillion.“

Meanwhile, Sauron was growing in power and steering clear of Lindon. In fact, “elsewhere the Elves received him gladly, and few among them hearkened to the messengers from Lindon bidding them beware; for Sauron took himself a name of Annatar, the Lord of Gifts, and they had much profit from his friendship.”

Much like the Númenóreans, these Noldor of Eregion had their pride get in the way. They let Annatar give them advice on how to create, how to live, and how to rule. They even “refused to return into the West, and they desired to stay in Middle-earth.”

“In those days the smiths of Ost-in-Edhil surpassed all that they had contrived before; and they took thought, and they made Rings of Power.” Moreover, they did so under Sauron’s guidance, taking his advice in the Rings’ creation.

The Elves created many of these Rings, “but secretly Sauron made One Ring to rule all others, and their power was bound up with it, to be subject wholly to it and to last only so long as it too should last.” I think anyone who is reading this has heard of this Ring before. The One Ring allowed Sauron to rule and influence the decisions of those who wore the lesser rings.

But the Elves immediately understood their gaff: “As soon as Sauron set the One Ring upon his finger they were aware of him; and they knew him, and perceived that he would be master of them, and all they wrought.”

The Elves took off their rings and hid them away, but Sauron could feel them, and in his great wrath, he waged war against the Elves to take the rings back, “But the Elves fled from him; and three of their rings they saved, and bore them away, and hid them.“

They saved the rings of the greatest power, Narya, Nenya, and Vilya.

Narya was called the Ring of Fire and inlaid with a Ruby. Nenya was called the Ring of Water and inlaid with adamant, and Vilya was called the Ring of Air and inlaid with a sapphire.

The rings could “ward off the decays of time and postpone the weariness of the world.” But they were kept secret and not worn while Sauron wore the One Ring. “Therefore, the Three remained unsullied, for they were forged by Celebrimbor alone, and the hand of Sauron had never touched them.”

However, Sauron never gave up his quest for power over the rings and battled against the Noldor incessantly. During this time, “Eregion was laid to waste, and Celebrimbor slain, and the doors of Moria were shut. (Celebrimbor sealed the gates of Moria using Mithril and Elven magic. These are the gates we see the fellowship open in “The Fellowship of the Rings” by speaking the Elvish word for Friend).”

Because Sauron was raging so hard against the Elves, Elrond founded Rivendell as a sanctuary, as a way to rally against Sauron. It is here we get the opening quote to this essay.

The Rings given to the Dwarves were of Gold, matching their heart’s greed. These golden rings kindled the evil of profits in their hearts and they hoarded Gold, “but all these hoards long ago were plundered, and the Dragons devoured them.“

Men took nine of the rings, which gave them eternal life, “yet life became unendurable to them.” Then eventually, “they could see things in worlds invisible to mortal men; but too often they beheld only the phantoms and delusions of Sauron.“

The nine men who held the Rings fell into thralldom to Sauron, “And they became for ever invisible save to him that wore the Ruling Ring, and they entered into the realm of shadows. The Nazgûl were they, the Ringwraiths, the Enemy’s most terrible servants; darkness went with them, and they cried with the voices of death.“

Join me next week for a breakdown of Episode 6 of The Rings of Power before we jump back into the next section, “Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age!”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Akallabêth, Part 3

“Then behind locked doors Sauron spoke to the King, and he lied, saying: ‘It is he whose name is not now spoken; for the Valar have deceived you concerning him, putting forward the names of Eru, a phantom devised in the folly of their hearts, seeking to enchain Men in servitude to themselves. For they are the oracle of this Eru, which speaks only what they will. But he that is their master shall yet prevail, and he will deliver you from this phantom; and his name is Melkor, Lord of All, Giver of Freedom, and he shall make you stronger than they.’“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we continue on our journey in Númenor and watch as the once-great empire begins to collapse.

We left off last time with the fact that the Valar were angered at Númenor and cut off ties with them. The lack of Valar support didn’t affect the mainland, but some were still faithful to the Valar and the Eldar, and they lived in a kingdom on the western shores in a city named Andúnië. The Men (read that as humans) who lived there “were of the line of Elros, being descended from Silmarien, daughter of Tar-Elendil, the fourth King of Númenor.” It was this line of Elros’ goal to unite the people of Middle-earth instead of trying to rule over them like the rest of the Númenóreans. In fact, Aragorn is a descendant of the Andúnië, and it’s his shame of what the Númenóreans eventually did that made him stay away from the crown for so long.

Years passed, and King begat King, until the beginning became the beginning of the end. Then, Tar-Palantir took the scepter and became King. He took an Elvish name (his Númenórean name was Inziladûn), and for the first time in years, a King of Númenor had used the dialect of a race the Númenóreans had begun to hate. He was a seer, so he took the name of the Palantirí, the seeing stones. One of his prophecies was that when the great “White Tree perished, then also would the line of the Kings come to its end.“

Tar-Palantir tried to bring back the old ways, but it was too little, too late. His daughter took to the throne after he died, “whom he named Míriel (whom you might know as the Queen Regent if you watch The Rings of Power on Amazon) in the Elven tongue.” But her first cousin Pharazôn was power hungry and hated the Valar for forsaking them, so he “took her to wife against her will, doing evil in this and evil also in that the laws of Númenor did not permit marriage, even in the royal house, of those more nearly akin than cousins in the second degree.”

Ar-Pharazôn became the most guilded of all kings to rule Númenor…and the proudest. His men told him that Sauron was building strength in the East, and in his hubris, he sent a contingent of men to capture Sauron. But the Dark Lord outwitted the Golden King and waved the white flag. So Ar-Pharazôn took him captive in Númenor, thinking he would keep the enemy close.

“Yet such was the cunning of his mind and mouth, and the strength of his hidden will, that ere three years had passed he head become closest to the secret councils of the King.“

The men of Númenor began to fall under Sauron’s sway, “save one alone, Amandil lord of Andúnië.” Of the Line of Aragorn. The men of this line remained faithful to the Valar and the Eldar, but the rest of Númenor “named them rebels.“

The quote which opens this essay is one of the examples of the cunning of Sauron. He twisted history and played upon the Númenórean beliefs, making them believe that Melkor was the true Lord and not Ilúvatar (also named Eru, as seen above). But, unfortunately, because of the pain of the Valar rejection and their own belief that they are better than any other race, the half-truths of Sauron rang true to them, and “Ar-Pharazôn the King turned back to the worship of the Dark, and of Melkor the Lord thereof, at first in secret, but ere long openly and in the face of his people; and they for the most part followed him.”

With this belief in the Dark Lord, Ar-Pharazôn threw Amandil, the Elf-friend of Andúnië and out of his council. But Amandil, along with his son Elendil, were the most significant ship captain of Númenor, so they were kept in Númenor, despite their outward rejection of the worship of Melkor.

While shunned, Amandil heard that Sauron had advised Pharazôn to cut down Nimloth, the white tree. Knowing of Tar-Palantir’s prophesy, he gathered his son Elendil and his grandchildren Isildur and Anárion. He told them the tale of the Trees of Valinor and the glory of the Valar.

“…Isildur said no word, but went out by night and did a deed for which he was afterwards renowned.”

Young Isildur went to Nimloth and stole its fruit. The guards gravely injured him, but he managed to escape and bring the fruit to his Grandfather, who planted it in secret. Upon its first bloom, Isildur was miraculously healed, showing the power of the Valar.

Soon after, the new tree bloomed just in time because “the King yielded to Sauron and felled the White Tree, and turned wholly away from the allegiance of his fathers.”

Ar-Pharazôn ordered that a gilded tower be turned into a fire altar and burned Nimloth so that “men marveled at the reek that went up from it, so that the land lay under a cloud for seven days, until slowly it passed into the west.“

“Thereafter the fire and smoke went up without ceasing; for the power of Sauron daily increased, and in that temple, with spilling of blood and torment and great wickedness, men made sacrifice to Melkor that he should release them from Death. And most often from among the Faithful they chose their victims.”

The Doom of Númenor has begun. Join me next week as we continue with Episode 4 of The Rings of Power and the week after when we return and complete Akallabêth!

Blind Watch: The Rings of Power; Episode 2, Adrift

“No! This is different. He could have landed anywhere and he landed here. I know it sounds strange but somehow I just know he’s important. It’s like there’s a reason this happened, like, I was supposed to find him. Me. I cant walk away from that, not, until I know he’s safe. Can you?“

Welcome to another Blind Watch! This week we delve back into Amazon’s realization of Middle-earth with the second episode of “The Rings of Power.” Be warned now! This blog is meant to be read after watching the episode. There are heavy spoilers and explanations of the episode, so please watch before reading!

This episode, “Adrift,” follows a stranded Galadriel in the middle of the sea. Arondir as he searches for the root of the plague. Nori Brandyfoot finds a mysterious giant and tries to befriend him. Then lastly, Elrond brings us to see the Dwarves of Khazad-Dûm.

Though the title is a metaphor for all the characters and the uncertainty of what is to come, let’s begin with the most apparent message and cover Galadriel.

A group of shipwreck survivors finds her floating in the ocean. A creature they call the worm attacked them, which is some giant sea creature. It harasses them and breaks up their flotilla, leaving only one survivor after its destruction. However, Galadriel does see (with her elf eyes) some spear impaled into its tail fin. I’m sure there is a significance that I’m missing at the moment, but it’s something to remember moving into future episodes.

In the Silmarillion, many creatures remained undescribed and grew in the darkness of Middle-earth. They were creatures of Morgoth’s creation because he corrupted the land. I believe that this sea creature, this “worm,” is one of those creatures, and it’s fun to see what the imaginations of Amazon can come up with because they have such an open slate.

The last survivor, Halbrand, lets Galadriel know that Orcs destroyed his home, Orcs that were supposed to be gone from the region. Instead, we find that the Orcs come from the Southlands, which we already know from Arondir’s storyline. Eventually, they are seen by someone on a ship, who undoubtedly is a Númenórian.

Moving back to Arondir’s storyline, he heads to the Southlands and finds a city that has been destroyed from beneath. The scourge is Orc that has tunneled underneath the earth and popped up to sack the city. He and Bronwyn find enough evidence to realize that Bronwyn’s town is in danger. They head back to find that Orc’s have come from underneath, and there is a fun fight scene towards the end of the episode where they fight and kill one of the orcs.

The mystery here is Theo, who is Bronwyn’s son. He has a sword hilt with Sauron’s mark on it, and the question is, where did he get that hilt? Could Theo be Halbrand’s son? Could the mysterious broken sword have come from a previous battle where Sauron was defeated? We are led to believe that Sauron’s armies heeded the call of the sword hilt, so all those questions remain to be answered.

Elrond’s storyline is the least impressive of the episode and takes up most of the run time. However, the whole point of the storyline is a setup for the rings of power in general. Elrond meets up with Celebrimbor, the premier elvish smith who wants to create something spectacular. However, he somehow lacks the ability, so Elrond takes him to visit his “friend” (speak friend and enter) Prince Durin. The goal is to get Prince Durin and Celebrimbor together to create what can only be the Rings of Power. There is also a decent amount of back and forth about Dwarvish/Elvish relations, which will only enrich the later storylines.

The final storyline is, to me, the most interesting and is represented by the quote at the beginning of this essay. It follows Nori, who is a precursor to the Third Age Hobbits we know and love (based upon the name, I have to imagine she is a descendant of the Proudfoot and the Brandywine Hobbit lines).

Nori finds the mysterious giant who has some magical powers. I think the showrunners are taking a little more creative license here because I believe this being is a Maiar named Olórin, otherwise known in Middle-earth as Gandalf.

The Maiar are basically celestial beings, second only to the Valar, and indeed are servants of the Valar (Morgoth is and was Valar, and Sauron is his Maiar adjutant). The Istari were a sect of Maiar “wizards” sent to Middle-earth to assist the people against Sauron’s deception and armies. At the end of the first episode we see this giant being shot down to the earth like a meteor, and spends the majority fo the second episode trying to learn speech, and to understand his magic.

That follows with the general storyline of The Silmarillion, but the only issue is that the Istari were all sent in the Third Age, not the Second Age, so the showrunners are ignoring some history of Middle-earth here to work to make a better and more fluid show.

The whole of what I know about the Second Age comes from Akallabêth, which I’ve just finished, and we’ll get a Blind Read over the next few weeks to complete it. The issues I see here are that in the Second Age, Sauron worked his silver tongue to fool the great kingdoms of Middle-earth. He became a consultant of the Númenórians and created distrust from the inside rather than fighting them directly.

Sauron’s real story may still be the case in the show because we are just getting to Númenor in the next episode, but because there are already armies of Orcs fighting, and no one seems to know where Sauron is, I don’t think this is the direction they’re going.

It also is a complete divergence for Galadriel’s character because she was a fighter, but at this point in history, she was married to Celeborn and living peacefully, but there is no mention of him in the show. It was Morgoth who killed her brother, not Sauron, so her motivation has changed entirely.

Despite all that, it’s fun to be back in Middle-earth on screen, and I can’t wait to see their take on Númenor!

Join me next week as we continue with Akallabêth. We will switch back and forth between Blind Reads and Blind Watch every week for the next few weeks, as the last two chapters in the Silmarillion pertain to what is happening in “The Rings of Power.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Akallabêth, part 1

“And the Doom of Men, that they should depart, was at first a gift of Ilùvatar. It became a grief to them only because coming under the shadow of Morgoth it seemed to them that they were surrounded by a great darkness, of which they were afraid; and some grew wilful and proud and would not yield , until life was reft from them. We who beat the ever mounting burden of the years do not clearly understand this; but if that grief has returned to trouble you, as you say, then we fear that the Shadow arises once more and grows again in your hearts.“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we delve into the Decendents of Elves and Men, otherwise known as the Númenorians or Dúnedain.

Tolkien begins the chapter by giving us an abridgment of the story of Men in The Silmarillion, but with a slight adjustment: “It is said by the Eldar that Men came into the world in the time of the Shadow of Morgoth, and they fell swiftly under his dominion; for he sent his emissaries among them, and they listened to his evil and cunning words, and they worshipped the Darkness and yet feared it.“

Interestingly, he begins this chapter from the perspective of the Eldar because the majority of the end of The Silmarillion has to do with how the “men” (meaning humans) helped with the ultimate defeat of Morgoth. Indeed without their influence, Morgoth would probably have taken over the land of Middle-earth.

What I find so fascinating about this passage is that Tolkien is saying that the majority of Men in the first age fell under Morgoth’s deception. However, just a select few, the Edain, who made their way West into Beleriand, were free of The Dark Lord’s corruption. Indeed, these Edain are whom we’ve read about thus far in the Quenta Silmarillion.

With Morgoth’s defeat, his thralls went back into the east, and the Edain faithful to the Valar were rewarded for their servitude. “Eönwë came among them and taught them; and they were given wisdom and power and life more enduring than any others of mortal race have possessed.”

They were also given land that was “neither part of Middle-earth nor of Valinor, for it was sundered from either by a wide sea.” The Valar raised the ground from the sea and enriched it with life, and the Star of Eärendil shone like a northern light to show the Edain how to reach that land. The land was called Andor, or “Númenóre in the High Eldarin tongue.“

“This was the beginning of that people that in the Grey-elven speech are called the Dúnedain: the Númenóreans, Kings among Men.“

These “Kings among Men” were blessed with abnormally long lives to allow them to gain wisdom and help with the progression of Men in Arda, but the original gift of Ilùvatar was still intact. The gift of death.

Ilùvatar (you can read this as God) wanted Men of Middle-earth to have the ability to die, so he gave them short lifespans. The Valar are eternal, and the Eldar are immortal unless mortally injured. So men were given short lives to appreciate the splendor that Ilùvatar and the Valar had wrought. The drawback was that none of the great human kingdoms of the First Age could produce the marvels that the Elves or even Dwarves were able to create. Thus Númenor allowed them to grow “wise and glorious, and in all things more like the Firstborn than any other of the kindreds of Men; and they were tall, taller than the tallest sons of Middle-earth; and the light of their eyes was like the bright stars.“

It was here on Númenor, the island kingdom, that Elros, brother to Elrond and son of Eärendil and Elwing, became the first King of the Dúnedain in the great city of Armenelos.

Because of his parent’s sacrifice and their mixed blood, the Valar gave the brothers the choice of whom they would live their lives. Elrond chose Noldor blood and lived the rest of his life amongst the Elves. Elros, however, decided the blood of Man, and it’s from his shared blood that the Númenórian line descended.

Elros ruled in splendor for over four hundred years, growing Númenor into the legend it would become. “The Dúnedain dwelt under the protection of the Valar and in the friendship of the Eldar, and they increased in stature both of mind and body.”

They accepted a ban from the Valar that they were not to sail to the west and thus spent their time growing in knowledge and the arts. They became great shipbuilders, as you would expect of people living on an island. They accepted gifts from the Valar and planted seedlings of the great trees of Valinor, echoing Telperion. I have to wonder if this is the antecedent of the great white tree of Gondor we see in The Lord of the Rings. The men of Gondor were, in essence, descendants of the Dúnedain, so having the tree be the standard on their armor and flags makes sense, especially because Aragorn was a descendant of those great kings.

It was during this time that Middle-earth’s wisdom faded, all while the Númenórian knowledge increased. It was only a matter of time before the Dúnedain would make their way to the mainland. Over the years of building ships and gaining their knowledge, a natural curiosity about the surrounding world cropped up among the Dúnedain. They were denied the ability to sail west, so naturally, they sailed east to Middle-earth’s dark lands.

This was the beginning of the corruption of the Dúnedain. They came as seekers of knowledge but went to the land that had regressed. They came to a land of people who had become hunter-gatherers and lived tribally. They came as wanderers and became conquerors. They became, in their own eyes, Gods of Middle-earth.

Join me next week as we review the second episode of The Rings of Power before returning to the saga of the Dúnedain!

You must be logged in to post a comment.