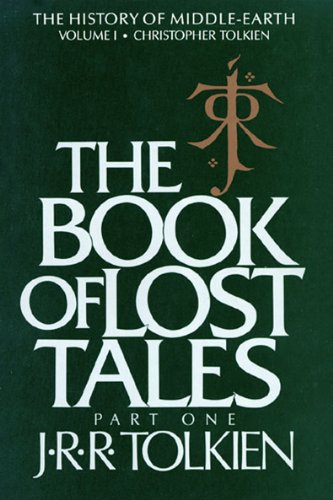

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2; Túrin’s last tragedy

“There did she stay her feet and standing spake as to herself: ‘O waters of the forest whither do ye go? Wilt thou take Nienóri, Nienóri daughter of Úrin, child of woe? O ye white foams, would that ye might lave me clean – but deep, deep must be the waters that would wash my memory of this nameless curse. O bear me hence, far far away, where are the waters of the unremembering sea. O waters of the forest wither do ye go?’ Then ceasing suddenly she cast herself over the fall’s brink, and perished where it foams about the rocks below; but at that moment the sun arose above the trees and light fell upon the waters, and the waters roared unheeding above the death of Nienóri (pg 109-110).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we conclude the tale of Turambar and the Foalókë and experience the last tragedies of Turambar’s life.

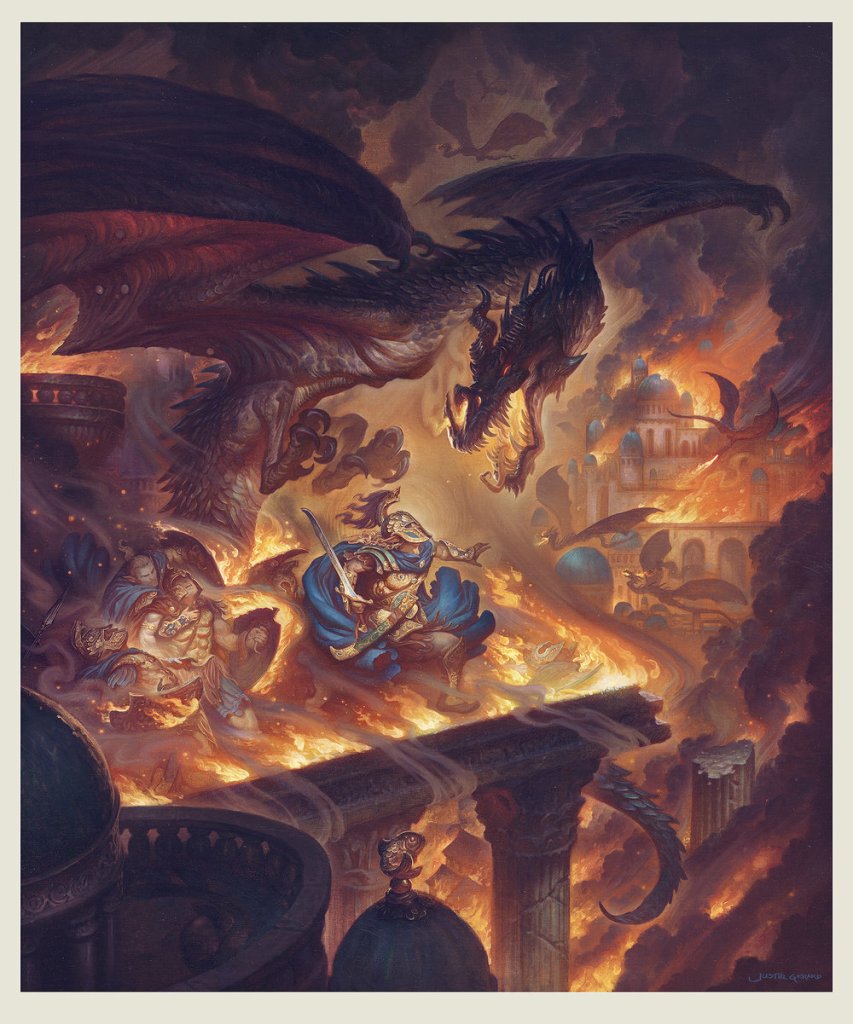

We left off last week with Turambar and Níniel deciding to ride out against the Foalókë, Glorund, to kill the drake. They gathered with them a group of men desperate to rid their land of the terrible beast, but on the way to the drake, they slowly abandoned the mission, leaving only a handful of mercenaries left, and “Of these several were overcome by the noxious breath of the beast and after were slain (pg 104).”

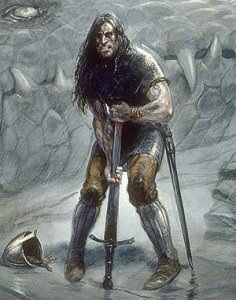

Eventually, only Turambar and Níniel were left to face the beast. “Then in his wrath Turambar would have turned his sword against them, but they fled, and so was it that alone he scaled the wall until he came close beneath the dragon’s body, and he reeled by reason of the heat and of the stench and clung to a stout bush.

“Then abiding until a very vital and unfended spot was within stroke, he heaved up Gurtholfin his black sword and stabbed with all his strength above his head, and that magic blade of the Rodothlim went into the vitals of the dragon even to the hilt, and the yell of his death-pain rent the woods and all that heard it were aghast (pg 107).”

The death of Glorund would seem like a cause for celebration, but unfortunately, Turambar’s efforts to end the scourge of the great worm only ended up in more tragedy.

His death was foretold from his early mistakes, and if he had only taken a little more time and been less impetuous, his life wouldn’t have ended up the way it was. Turambar is an echo of Hotspur, the firey prince of Shakespeare’s histories, where he has everything going for him, but because of his temper and strong desires, his life is degraded.

So how could Turambar’s life degrade from killing the drake, you might ask? Well, he passes out next to the Foalókë, and when Níniel comes to find him, she thinks he died along with the dragon in mortal combat. She weeps next to Turambar. She weeps for her husband. She cries for the man who killed the dragon and saved their people. But her weeping wakes Glorund for one last gasp.

“But lo! at those words the drake stirred his last, and turning his baleful eyes upon her ere he shut them for ever said: ‘O thou Nienóri daughter of Mavwin, I give thee joy that thou has found thy brother at last, for the search hath been weary – and now is he become a very mighty fellow and a stabber of his foes unseen (pg 109).”

Glorund died with these words, but what fell with the great beast was the glamor he held over Nienóri. She was suddenly aware of who she was and who Túrin was. Realization bombarded her that she had been married to her brother and had children with him. Aghast at the knowledge, she heads off to a waterfall called the Silver Bowl, contemplative. But instead of Nienóri coming to terms with the events of the last number of years, she is overwhelmed, and we get the quote that opens this essay.

Túrin wakes and quickly realizes that she is gone. He heads back to the village where the people already know the secret of their king and queen, and Túrin pulls it out of them. This being Túrin and his tragic story, he responds how you would expect him to:

“So did he leave the folk behind and drive heedless through the woods calling ever the name Níniel, till the woods rang most dismally with that word, and his going led him by circuitous ways ever to the glade of Silver Bowl, and none had dared to follow him (pg 111).”

Túrin turns to his sentient sword and begs for the only absolution his troubled life could understand.

“‘Hail Gurtholfin, wand of death, for thou art all men’s bane and all men’s lives fain wouldst thou drink, knowing no lord or faith save the hand that wields thee if it be strong. Thee I only have now – slay me therefore and be swift, for life is a curse, and all my days are creeping foul, and all my deeds are vile, and all I love is dead (pg 112).'”

“and Turambar cast himself upon the point of Gurtholfin, and the dark blade took his life (pg 112).”

The tale doesn’t end here, however; Tolkien switches us back to Mavwin and her search for her children. She wept and went into the woods, and the region of Silver Bowl became haunted by their past and presence.

Tolkien also lays on some of his Christianity, which is notably absent in the later editions:

“Yet it is said that when he was dead his shade fared into the woods seeking Mavwin, and long those twain haunted the woods about the fall of Silver Bowl bewailing their children. But the Elves of Kôr have told, and they know, that at last Úrin and Mavwin fared to Mandos, and Nienóri was not there nor Túrin thier son (pg 115).”

Both the children ended up as spirits because their transgressions forbade them from the afterlife.

Join me next week as we dive more into the religion of the story and break down just what Tolkien was going for with such a horrifically tragic story.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2, Túrin’s Second Tragedy

“In that time was Túrin’s hair touched with grey, despite his few years. Long time however did Túruin and the Noldo journey together, and by reason of the magic of that lamp fared by night and hid by day and were lost in the hills, and the Orcs found them not.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we cover Turambar’s second tragedy and discover his life and vision of himself as an outlaw and what that means for him moving into the rest of his story.

We left off last week with Túrin leaving Doriath and heading off into the wilds, where he met up with Beleg, an Eldar of the court of Tinwelint. Tolkien spent time developing Beleg later in the Silmarillion (probably to give Túrin’s actions more significant stakes). Still, in this version, he becomes a traveling companion and a Captain against Melko.

The two range in the wilds and hunt orcs and other foul creatures of the darkness. For many of these hunters, the goal was to lessen Melko’s hold on the world and make it a little more accessible for everyday people to wander. For Túrin, it was about killing these foul creatures, which showed his true nature.

In the Silmarillion, Beleg played the role of the conscious. Túrin ran off with the outlaws, and Beleg was sent after him to be a protector and to remind him of his upbringing. There is even a sentiment that Beleg should bring Túrin back if possible, and he is given the Dragon Helm of Dor-lómin to give to Túrin to show that even if he doesn’t come back, they wish him to be safe.

In The Book of Lost Tales, Beleg is already out in the wilds, and Túrin joins him. Their bond is strong, and they become like brothers out in the wilds hunting the creatures of Melko. But living that life can only last so long before life catches up with you.

It wasn’t long before they came across “a host of Orcs who outnumbered them three times. All were there slain save Túrin and Beleg, and Beleg escaped with wounds, but Túrin was overborne and bound, for such was the will of Melko that he be brought to him alive (pg 76).”

Túrin stayed a captive of the Orcs for some time. They abused and beat him to within an inch of his life, and “was Túrin dragged now many an evil league in sore distress (Pg77).”

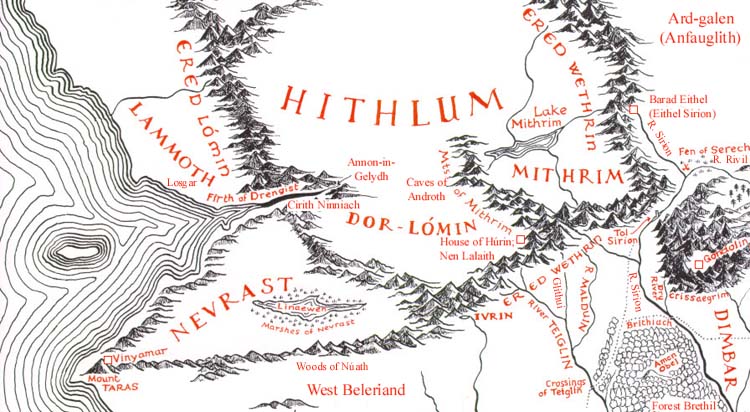

During this time, Melko unleashed “Orcs and dragons and evil fays (pg 77)” upon the people of Hithlum to either take them as thralls or kill them as retribution for the outlaw brigade led by Túrin.

Meanwhile, Beleg wandered in the wilds, killing evil creatures and looking for his lost compatriots. He did so until he came upon an encampment of Orcs and saw that in this camp was a restrained Túrin. Thus, we get Túrin’s second great tragedy:

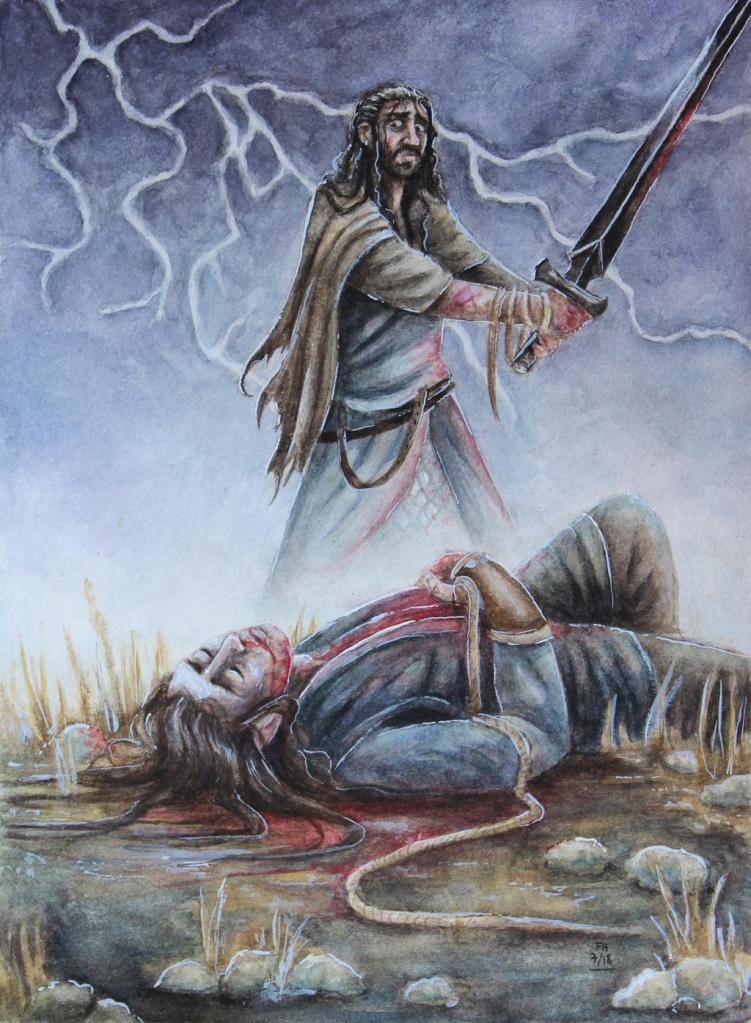

“but Beleg fetched his sword and would cut his bonds forthwith. The bonds about his wrists he severed first and was cutting those upon the ankles when blundering in the dark he pricked Túrin’s foot deeply, and Túrin awoke in fear. Now seeing a form bend over him in the gloom sword in hand and feeling the smart of his foot he thought it was one of the Orcs come to slay him or torment him – and this they did often, cutting him with knives or hurting him with spears; but now Túrin feeling his hand free lept up and flung all his weight suddenly upon Beleg, who fell and was half-crushed, lying speechless on the ground; but Túrin at the same time seized the sword and struck it through Beleg’s throat…(pg 80).”

Túrin felt like an outcast because he was a man living with Elves and his accidental killing of Orgof, but now, with the murder of Beleg, he has become a full-fledged Outlaw. It is not in his nature to return to Tinwelint and confess his wrongdoing, even if the Elven King would forgive and pardon him. Túrin internalizes his struggles and becomes depressed in the way only a Man (human) can.

Tolkien wrote the races of Middle-earth (I have still not seen a mention of Beleriand yet in The Book of Lost Tales) to have all range of emotion, but Elves never really seem to get maudlin like Men do. Their immortality gives them a view of the world that eliminates general depression, but Man’s mortality appears to encourage it. We see that slightly in Beren, but it is full front and center for Túrin. His entire story has a sort of “woe is me” feel – even though it’s his fault that these things happen to him. Túrin lives his life in a state of impetuousness, which leads to desperation. In that desperation, he takes events as they come to him without giving them a second thought.

So when he escapes the Orcs with the Elf Flinding, who incidentally is also a bit of an outcast for his actions, they come across a group of wandering Men called the Rodothlim who live in caves.

The Rodothlim “made them prisoners and drew them within their rocky halls, and they were led before the cheif, Orodreth (pg 82).”

Here in the caves of the Rodothlim (which I believe must be a precursor to the Rohirrim), Túrin met Failivrin, a maiden of those people. She quickly met the dreary man and “wondered often at his gloom and sadness, pondering the sadness in his breast (pg 82).”

Despite her affection for him, Túrin couldn’t leave his past behind, “but he deemed himself an outlawed man and one burdened with a heavy doom of ill (pg 82-83).”

The caves of the Rodothlim had a strange effect on Túrin. Those people survived in the wilds because their caves gave them a veil from Melko’s agents and eyes, which gave Túrin a respite from having to face those monsters directly – but it also gave him time to think, dream, and replay his past life. In those caves of safety, Túrin made a mental shift and knew he could never be accepted in any typical setting. He was born an outlaw, and his fate was exclusively intertwined with that life. He decided to lean into the outlaw life, which was just one more bad decision in a long list of bad choices.

Join me next week as we continue on Túrin’s tragic journey!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Tale of Tinúviel, commentary

“In the old story, Tinúviel had no meetings with Beren before the day when he boldly accosted her at last, and it was at that very time that she led him to Tinwelint’s cave; they were not lovers, Tinúviel knew nothing of Beren bu that he was enamoured of her dancing, and it seems that she brought him before her father as a matter of courtesy, the natural thing to do (pg 52).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we’ll briefly cover Christopher’s commentary on The Tale Of Tinúviel and give some final thoughts on the story.

Much of what Christopher covers (Christopher is J.R.R. Tolkien’s son and editor. This book is posthumously published, and Christopher both compiled it and edited it) in his lengthy comments following the Tale of Tinúviel are the same or very similar to everything that I have covered in the previous Blind Reads, so we’ll speak about the most critical insights and give some context.

Before we jump into that, however, Christopher included a second draft (or at least pieces) of The Tale of Tinúviel just after the first edition and before his comments.

“This follows the manuscript version closely or very closely on the whole, and in no way alters the style or air of the former; it is, therefore, unnecessary to give this second version in extenso (pg 41).”

The most significant change that I noticed was the nomenclature. The forest’s name changed to Doriath, and the names Melian and Thingol are introduced here for the first time.

We also have the adjustment of Beren’s father from Egnor to Barahir and Angamandi to Angband. Most importantly, we first mention Melko as Morgoth (The Sindarin word for Melkor).

This last adjustment may seem like an alteration of monikers to streamline the narrative; however, knowing how The Silmarillion was published and the extensive lists of names, not to mention the number of names in each language many of the characters had, we know he did this intentionally.

Many people assume (and rightly so because the theory has become so ubiquitous) that Tolkien built a language (Elvish) and then developed a story and world based on that language. This theory makes a certain amount of sense because he was a linguist. Still, read these books (or, more importantly, Christopher’s annotation). You’ll understand that the world-building and the language came conjointly because of Tolkien’s desire to tell a fairy tale that would become England’s own. It was all supposed to start with this first story: The Tale of Tinúviel.

The names evolved because Tolkien was developing his language and the world the story took place in, and the names he originally used no longer made sense.

A prime example of this is in the second version of the story, “Beren addresses Melko as ‘most mighty Belcha Morgoth (pg 67).'” I’ll let Christopher explain:

“In the Gnomish dictionary Belcha is given as the Gnomish form corresponding to Melko, but Morgoth is not found in it: indeed this is the first and only appearance of the name in the Lost Tales. The element goth is given in the Gnomish dictionary with the meaning ‘war, strife’; but if Morgoth meant at this period ‘Black Strife’ it is perhaps strange that Beren should use it in flattering speech. A name-list made in the 1930s explains Morgoth as ‘formed from his Orc-name Goth ‘Lord of Master’ with mor ‘dark or black’ prefixed, but it seems very doubtful that this etymology is valid for the earlier period (pg 67).”

Tolkien was evolving and creating new languages for the Eldar and the Orcs, Dwarves, and Valar. Beyond that, he was developing dialects within these languages, so a Sindarin name would be different from a Noldoli name, which is where many people get confused about the number of names in The Silmarillion and how the rumor got started that Tolkien created the languages first and the world second. The above quote is the irrefutable proof (not to mention the extensive changes to The Lost Tales).

We can see the linguistic changes Tolkien is making, which in turn changes the story’s core, but there is some very interesting world-building that Tolkien has done in the augments between drafts.

The first example surrounds the Simarils; “The Silmarils are indeed famous, and they have a holy power, but the fate of the world is not bound up with them (pg 53).”

Tolkien understood the Maguffin (a plot device that sets the characters into motion and drives the story) early on. Still, his original intention was to tell the tale of two lovers, he and Edith, but in the names of Beren and Lúthien (Tinúviel). What he came to realize as he went through drafts and started to build the history of the world (this second version was also the first mention of Turgon the King of Gondolin because Tolkien had begun working on the story The Fall of Gondolin before he went back to the second draft of the Tale of Tinúviel), was that there needed to be a through line to bring the different tales together into one single history, rather than having a bunch of disparate short stories spattered throughout history. The Silmarils became that Maguffin. They grew in mystery and power in his mind. The tale of Valinor became the precursor and introduction to the power that the Silmarils contained so that they might tell a much larger story and have the whole of the world seeking the power they held (much like the One Ring in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings).

The Tale of Tinúviel is a fascinating addition to the Legendarium, but it does feel a little one-note beside its later counterpart, Of Beren and Lúthien. What is most interesting is the fairy tale manner in which Tolkien tells the tale. The first big bad we see is a cat who captures our hero and makes him hunt for them because they’re lazy cats. This anthropomorphized creature is a common theme in fairy tales, and Tevildo never truly poses a real threat, especially when Huan the Hound shows up. Then, when Tinwelint imprisons Tinúviel in a tall tower to keep her from going after her love, we get impressions of all the old Anderson Fairy Tales. In this early version, it is apparent that Tolkien was going for a fairy tale vibe (which in fact was his original intention before realizing that he wanted to make it more realistic, more gritty), but instead of eventually disneyfying it, he went deeper and darker and turned the tale into something bold and breathtaking, and seeing the transformation is something to behold.

We’ll take a week off before returning to the next story, “Turambar and the Foalókë.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2; The Tale of Tinúviel, cont.

“Now all this that Tinúviel spake was a great lie in whose devising Huan had guided her, and maidens of the Eldar are not wont to fashion lies; yet have I never heard that any of the Eldar blamed her therein nor beren afterward, and neither do I, for Tevildo was an evil cat and Melko the wickedest of all beings, and Tinúviel was in dire peril at their hands (pg 27).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! We left off last week with Beren getting captured by Tevildo, Prince of Cats, and Lúthien escaping the tower her father imprisoned her in to go and find and free Beren from his thralldom.

Before the story, let’s review what happened in The Silmarillion.

Lúthien escaped from Doriath and chased after Beren, but where there are cats in The Book of Lost Tales, The Silmarillion had Wolves. Beren was captured by Sauron, the Master of Wolves (many of his minions in this story were werewolves, and he even commanded the Wolf King Carcharoth), and on her way to find him, Lúthien meets up with Huan, the Hound of Valinor.

Huan takes Lúthien to his masters, Celegorm and Curufin, who were Fëanor’s sons (Eldar who swore to get the Silmarils back at the cost of all else). The Book of Lost Tales is a significant departure from the older story because these two brothers played a nefarious role in the remaining history of Beleriand. They caused strife and trouble for our heroes many times and generally stood in the way only because of their oath, and they never appear in the earlier version.

This deception is the first instance of their devious natures. They instructed Huan to bring Lúthien before them and once there, Celegorm devised a plan to marry her because of her beauty, but more importantly because of her lineage. Celegorm was seeking power, plain and simple. He tricks Lúthien, brings her to Nargothrond, and imprisons her until his plan can be complete.

Here, Huan felt pity for Lúthien, who only wanted to save her love, and felt disgust for his master. Huan frees Lúthien, leading her to Angband to confront Sauron and free Beren.

When they get there, Sauron sends his werewolves out to kill them, but Huan kills them one by one. Sauron then shapeshifts and changes himself into a werewolf (doubtless being one of those quintessential bad guys who say, “If you want something done right, you gotta do it yourself.”), and heads out to meet them. There is a pitched battle, with Sauron changing into different shapes and trying other tactics. Still, eventually, Huan defeats him, and Sauron flees in the form of a Vampire after leaving the keys to the prisons for Huan and Lúthien to take.

This fight shows the absolute power of Huan. Sauron gained strength and influence over the remaining years of his life, but the fact that Huan and Lúthien were able to best him in battle when, later on, it took armies to stand up to him is a testament to Huan’s strength and Lúthien’s ingenuity.

They freed Beren and fled Angband, only to come across our favorite dastardly Eldar, Celegorm, and Curufin. They battled, and Beren won, deepening their shame and anger. Not only were the great sons of Fëanor defeated, but a human bested them to boot!

Beren then snuck back to Angband after both Huan and Lúthien slept, determined to get the Simaril and prove his worthiness, but when they woke and found him gone, they disguised themselves as a vampire and werewolf and went after him. They got to Morgoth’s chambers, and Lúthien used her magic to put everyone to sleep and Beren cut a Silmaril from Morgoth’s crown before escaping from the stronghold.

As they exited, Carcharoth, the King of Wolves jumped out and attacked them, biting off Beren’s hand that held the Silmaril and thus halting their quest. Huan summoned The Eagles of Manwë (you might remember these majestic creatures from the end of The Return of the King when they rescued Frodo and Sam from Mount Doom), and they escaped from Angband.

In The Book of Lost Tales, Sauron is not present. Instead, it’s Tevildo who has Beren captured. Lúthien still meets up with Huan, but we have a sort of natural cat-and-dog relationship there:

“None however did Tevildo fear, for he was as strong as any among them, and more agile and more swift save only than Huan Captain of Dogs. So swift was Huan that on a time he had tasted the fur of Tevildo, and though Tevildo had paid him for that with a gash from his great claws, yet was the pride of the Price of Cats unappeased and he lusted to do a great harm to Huan of the Dogs (pg 21).”

Tinúviel travels with Huan to Angamandi (the early version of Angband) and finds a resting cat sentry just before its gates. Tinúviel asks to speak with Tevildo and plays to the guard’s pride to get her in to gain an audience.

When she is brought before Tevildo, she asks to speak with him privately, but he is not humored:

“‘Nay, get thee gone,’ said Tevildo, ‘thou smellest of dog, and what news of good came ever to a cat from a fairy that had dealings with dogs (pg 24)?”

Tinúviel sweet-talks her way in and spies Beren in the kitchen doing his thrall duties. She speaks loudly, letting Beren know that she’s there, and then we get the opening quote of this essay, where she divulges Huan’s plan: Huan is hurt and helpless just outside in the forest, the cats must kill him!

“Now the story of Huan and his helplessness so pleased him (Tevildo) that he was fain to believe it true, and determined at least to test it; yet at first he feigned indifference (pg 27).”

Tevildo and a small group of Cats went out to try and end Huan, only to fall into the trap. Huan killed all but Tevildo, who barely escaped and lost his golden collar before fleeing up a tree.

Tinúviel took the golden collar and brought it before Tevildo’s court and got all of his prisoners released, along with a curiously named Gnome.

“Lo, let all those of the folk of the Elves or of the children of Men that are bound within these halls be brought forth,’ and behold, Beren was brought forth, but of other thralls there were none, save only Gimli, an aged Gnome, bent in thraldom and grown blind, but whose hearing was the keenest that has been in the world, as all songs say (pg 29).”

This name was undoubtedly used again once the languages were fleshed out and Tolkien realized that Gimli was much more of a dwarven name than an Elvish name, but he doesn’t appear again in this story (that I’ve read so far), so I think it was just a name Tolkien loved.

Lúthien, Beren, and Huan escaped, and the cats were ashamed. Morgoth’s anger was so great that they lost face, and the power of the cats was never the same from then on.

We’re getting close to the end! Join me as we cover the first written ending to The Tale of Tinúviel next week!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Beren’s Beginnings

“‘Why! wed my Tinúviel fairest of the maidens of the world, and become a prince of the woodland Elves – ’tis but a little boon for a stranger to ask,’ quoth Tinwelint. ‘Haply I may with right ask somewhat in return. Nothing great shall it be, a token only of thy esteem. Bring me a Silmaril from the Crown of Melko, and that day Tinúviel weds thee, an she will (pg 13).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we dive into the Tale of Tinúviel, discover the differences between The Book of Lost Tales and The Silmarillion, as we begin one of Tolkien’s greatest tales.

We left off last week setting the stage for how Tolkien adjusted over time to have the story fit into his Legendarium. This week, we’re going to learn a bit more about Beren and get started on the tale itself!

Tolkien begins the tale with the lineage of Tinúviel and Dairon, as discussed last week, and then transitions into the story itself. “On a time of June they were playing there, and the white umbrels of the hemlocks were like a cloud about the boles of the trees, and there Tinúviel danced until the evening faded late, and there were many white moths abroad (pg 10).”

This play was a favorite pastime for both Tinúviel and Dairon. Dairon would play his music, and his sister would dance and sing like a nightingale in the forests of what would eventually be known as Doriath.

“Now Beren was a Gnome, son of Egnor the forester who hunter in the darker places in the north of Hisilómë. Dread and suspicion was between the Eldar and those of thier kindred that had tasted the slavery of Melko, and in this did the evil deeds of the Gnomes at the Haven of the Swans revenge itself (pg 11).”

Beren’s Genesis is an exciting story because while Tolkien was developing it early on, Beren was an elf (or, as Tolkien called them in The Book of Lost Tales, Gnomes).

The reason I chose the above quote was twofold. The first is the change of who Beren’s father was. In the Silmarillion, Beren is the son of Barahir and a descendant of Bëor, who was the leader of the first Men to come to Beleriand.

Barahir was a noble Man (When I capitalize “Man,” I’m using it in Tolkien’s manner, meaning human) who rescued Finrold Filagund from Dagor Bragollach (the Battle of Sudden Flame, otherwise known as the Fourth Battle of Beleriand), and received Finrold’s ring, which was later an heirloom of Isildur in Númenor.

In The Book of Lost Tales, Beren’s father is a Gnome named Egnor, who came to Beleriand early and became a thrall of Melkor. He eventually escaped and fathered Beren, but there was an intense distrust of any thrall of Melkor between the Gnomes.

So then Beren, when he comes across his Nightingale Tinúviel dancing in the forest, is the son of an outcast, which makes Tinwelint, Tinúviel’s father, very skeptical of him, because he is the son of someone who was a thrall of Melkor. Could that thralldom have been passed on? How could Tinwelint possibly trust him to be around his daughter?

Tolkien eventually wanted to change the storyline slightly, but the changes had the same effect. Beren became a Man instead of a Gnome, but Thingol was prejudiced against Men for two reasons. The first was because Men are attracted to power, and they woke after Melkor had done his earlier horrible deeds, so many Men latched onto his passion and became followers of Morgoth, the Dark Lord.

To the Elves, this was as bad or worse than thralldom. In the Silmarillion, it took many acts of Men to get Elves to trust them, and even then, they trusted the individual but still held a healthy distrust of the race.

The second reason Thingol didn’t like Beren and Lúthien’s connection was that Beren was a Man and thus mortal. If he let Lúthien fall in love with a mortal man, she would only have pain to look forward to because even though Men at this time in the Legendarium lived for over a hundred years, Elves were immortal. What was Lúthien to do when Beren died? We see this echo in The Lord of the Rings with Elrond as he speaks to Arwen about loving Aragorn.

So in both books, Tinwelint/Thingol makes a deal with Beren.

“‘Why! wed my Tinúviel fairest of the maidens of the world, and become prince of the woodland Elves – ’tis but a little boon for a stranger to ask,’ quoth Tinwelint. ‘Haply I may with right ask somewhat in return. Nothing great shall it be, a token only of thy esteem. Bring me a Silmaril from the Crown of Melko, and that day Tinúviel weds thee, an she will (pg 13).'”

Tinwelint knows that he is sending Beren off to his death. In the Book of Lost Tales, not a single Elf had gone up against Melkor because they knew him to be too powerful. Knowing that Beren’s father was a Thrall of Melkor, Tinwelint was probably hoping that Beren would have some genetic predisposition to stay under Melkor’s arm.

Nonetheless, Beren accepted:

“This indeed did Beren know, and he guessed the meaning of their mocking smiles, and aflame with anger he cried: ‘Nay, but tis too small a gift to the father of so sweet a bride. Strange nonetheless seem to me the customs of the woodland Elves, like the rude laws of the folk of Men, that thou shouldest name the gift unoffered, yet lo! I Beren, a huntsman of the Noldoli, will fulfil thy small desire,’ and with that he burst from the hall while all stood astonished (pg 13-14).”

Beren was off to go and collect the Silmaril, even though he knew it was a setup, but Tinwelint didn’t realize that as soon as night would fall, Tinúviel would steal away in the night to follow her love.

Join me next week as we continue the Tale of Tinúviel!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Lineage of Tinúviel

“Lo now I will tell you the things that happened in the halls of Tinwelint after the arising of the Sun indeed but long ere the unforgotten Battle of Unnumbered Tears. And Melko had not completed his designs nor had he unveiled his full might and cruelty (pg 10).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we begin Tolkien’s premier work in earnest and dissect the differences between what is in The Book of Lost Tales and what would eventually come in The Silmarillion.

The opening quote of this essay introduces the story to the reader, setting the stage for the events to come, but then Tolkien takes a step back and talks of the Elves of Doriath (which were not called such in this early version).

“Two children had Tinwelint then, Dairon and Tinúviel, and Tinúviel was a maiden, and the most beautiful of all the maidens of the hidden Elves, and indeed few have been so fair, for her mother was a fay, a daughter of the Gods; but Dairon was then a boy strong and merry, and above all things he delighted to play upon a pipe of reeds or other woodland instruments, and he is named now among the three most magic players of the Elves… (pg 10).”

If you have read The Silmarillion, you will probably recognize Tinúviel, and also Dairon as close to a character who stuck around. Still, otherwise, the names of the rest of the characters are entirely different.

Starting with our Titular character, Tinúviel, we know she kept that name in The Silmarillion. It’s the name Beren gave her because it means Nightingale, and he called her that when he found her dancing and singing in the forest. Her name changed to Lúthien, but there is still enough of a thread that it’s easy to keep everything in order.

Next, we have Tinwelint, who gained many names in the future as Tolkien began to develop his languages. Tinwelint became Elwë Singollo, leader of the hosts of the Teleri Elves, along with his brother Olwë. When Elwë led his people from Cuiviénen to Beleriand (the Teleri were known as the Last-comers, or the Hindmost, because, well, they were the last to come to Beleriand of the Eldar), he settled in the forests of Doriath (Where Beren saw Lúthien dancing). He ruled there under his better-known name, Elu Thingol.

Gwendeling, his wife, was not mentioned in the above quote but was also known as Wendelin in the Book of Lost Tales. She is a fay who falls in love with Tinwelint, marries him, and has two children.

Gwendeling, in my opinion, is how Tolkien decided to make the shift for the Maiar because, through the development of the Lay of Lúthien, he understood that women should play a much more significant role than he had initially been written (probably because of the influence of Edith). Gwendeling needed to possess powers of influence, most notably creating the Girdle of Melian, a protective shield over Doriath.

Because of this more extensive influence, Tolkien changed her lineage, and she became a Maiar, along with all of the other “children of the Valar” or Fay who never had a specific history. Doing so enabled Tolkien to have the Maiar keep their power set while at the same time lessening the ability of the Valar to have children (because if they are immortal, what is to stop them from continuing to have children who could potentially mess with the timeline)?

So Gwendeling became Melian the Maiar but stayed wife to Eru Thingol. That enabled Tolkien to make Lúthien a more robust character because she is the daughter of a demi-god and an immortal, but it left him in a strange quandary. In the book of lost tales, Tinúviel had a brother Dairon, and if he were to remain, he would also have to be a little more potent than the other Eldar because of his mother’s blood.

Dairon in the Book of Lost Tales is very talented, but one of those kids without any drive, as we see from the quote above. What he did possess, however, was an uncanny ability for music. He was considered the third-best “magic player” in the land, behind Tinfang Warble and Ivárë. You might remember Tinfang Warble from The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, because he was the half-fay flutist in the Cottage of Lost Play.

To adjust this inequity of power, Tolkien decided to slightly change Dairon’s name to Daeron, who then became one of the greatest minstrels of all time; in fact, the only being to come close to him was Maglor, Fëanor’s son (who is probably the later iteration of Ivárë). However, he became just a regular Eldar, no longer Thingol and Melian’s son, but rather a trusted loremaster of Thingol. More importantly, he was deeply in love with Lúthien.

This adjustment makes for a slightly better tale because rather than her brother betraying her excursion after Beren, it is an unrequited lover looking out for her best interest when he betrays her trust and tells Thingol that she went after Beren.

That takes care of the family, but what then of Beren? The most provocative change that Tolkien made here is that in the Book of Lost Tales, part two, is that Beren is an elf, not a man.

I believe he did this for several reasons, but two of them stand out to me the most:

- Men were not awake yet. At the end of the Book of Lost Tales, part 1, we see that they are children lounging by the Waters of Awakening. Tolkien didn’t spend time developing them like in The Silmarillion. Plus, The Silmarillion is considered the history of the Elves, even though much more happens there, so it makes sense that Beren would be an elf early on.

- Changing Beren to a Man adjusts the Legendarium in a fun and dynamic way. Now we have the dichotomy of the difference between Elves and Men and what that would mean for them to come together, fall in love, and potentially have children. The remainder of the time in Middle-earth stems from this relationship, so Tolkien needed to adjust it.

That was a lot to break down in just the opening pages! Join me next week as we dive into the story proper!

Blind Read Through: J.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Link of Tinúviel

“Then there was eagerness alight, and Eriol told them of his wanderings about the western havens, of the comrades he made and the ports he knew, of how he was wrecked upon far western islands until at last upon one lonely one he came on an ancient sailor who gave him shelter, and over a fire within his lonely cabin told him strange tales of things beyond the Western Seas, of the Magic Isles and that most lonely one that lay beyond. Long ago had he once sighted it shining afar off, and after had he sought it many a day in vain (pg 5).“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we begin The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, with the story of Middle-earth, which was closest to Tolkien’s heart.

This story is the earliest written tale in the Legendarium, even earlier than the tales of Ilúvatar and the Valar. Tolkien wrote the first manuscript in 1917 amid the Great War, and I have to imagine that he did so because he wanted a release from the horrors of the war happening around him.

Tolkien wrote the Tale of Tinúviel about his wife, Edith Tolkien, and it is both a beautiful homage and the seed from which all Middle-earth blossoms.

Those who know the story of Beren and Lúthien realize it is the tale of a man who falls in love with the most beautiful elven maid alive. Not only is she beautiful and sings like a nightingale, but she is a strong woman, a warrior, and a leader. Tolkien has been very forthright with the fact that Lúthien is, in fact, Edith, and the story of Beren seeing Lúthien singing and dancing in the forest was a call back to their walks in the dense woods of England when they first met.

This also means that the world of Middle-earth that Tolkien built would not be possible without Edith. Everything that happens in the Legendarium stems from this first origin (though doubtless there are poems written before this story, this was the first instance Tolkien wrote a new world through the lens of prose instead of poetry). Lord of the Rings even stems from this story. It echoes in Aragorn and Arwen, the Third Age’s version of Beren and Lúthien. There is even a passage in The Lord of the Rings compares Aragorn and Arwen to Beren and Lúthien.

This love story was at the core of everything that Tolkien wrote, and he built the greater Legendarium to support the story of his love for his wife. Though the tale grew beyond this conception, it remains the core of everything in Middle-earth.

Reviewing this tale will take multiple weeks, so to kick it off, I’d like to start with Eriol’s story and the link between where we left off in The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Also with where this book begins with The Tale of Tinúviel.

The tome takes up days after the events of Book of Lost Tales, part 1, with Eriol wandering in Kortirion, learning Elvish language and lore. One day as he is talking with a young girl and in a role reversal, she asks him for a tale:

“‘What tale should I tell, O Vëanne?’ said he, and she, clambering upon his knee, said : ‘A tale of Men and of childrren in the Great Lands, or of thy home – and didst thou have a garden there such as we, where poppies grew and pansies like those that grow in my corner by the Arbour of the Thrushes?'”

It may seem strange to call out this quote, but I do so because the passage ends here. Tolkien must have had the idea that Eriol would tell the history of Men, whereas the people of the Cottage of Lost Play would tell the story of the early times and the Elves.

Christopher gives a few different iterations of this interaction. Still, in every one of them, the story gets taken out of Eriol’s mouth as Vëanne interrupts him and begins the Lay of Lúthien (I.E., The Tale of Tinúviel).

I wonder if the intent was for Eriol to have his section of the book (which never actually happened) because Tolkien spends time here to set it up:

“‘I lived there but a while, and not after I was grown to be a boy. My father came of a coastward folk, and the love of the sea that I had never seen was in my bones, and my father whetted my desire, for he told me tales that his father had told him before (pg 5.)'”

The opening quote in this section talks about his “wanderings.” Before we get into the Tale of Tinúviel proper, there is also Eriol’s unwitting interaction with a Vala:

“‘For knowest thou not, O Eriol, that that ancient mariner beside the lonely sea was none other than Ulmo’s self, who appeareth not seldom thus to those voyagers whom he loves – yet he who has spoken with Ulmo must have many a tale to tell that will not be stale in the ears even of those that dwell here in Kortirion (Pg 7).'”

Eriol, to me, is a fascinating character because he has such a history, and he’s a mariner. If Tolkien created some stories from Eriol’s perspective, we might be able to see Middle-earth from a slightly different perspective, that of a sea-faring folk.

We know that all the history had come before this discussion. All of the first age (The Silmarillion) and the Second age (Akallabeth), and even the Third Age (The Lord of the Rings) came before Eriol’s time. So we can think of this soft opening in Kortirion as a Fourth Age, where Men (read Humans) run the world, the Elves have retreated to hidden Valinor, and much of the pain from the Dark Lord has disappeared, or at very least forgotten, from the world.

Join me next week as we start The Tale of Tinúviel!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1; Gilfanon’s Tale

“Suddenly afar off down the dark woods that lay above the valley’s bottom a nightingale sang, and others answered palely afar off, and Nuin well-neigh swooned at the loveliness of that dreaming place, and he knew that he had trespassed upon Murmenalda or the “Vale of Sleep”, where it is ever the time of first quiet dark beneath young stars, and no wind blows.

Now did Nuin descend deeper into the vale, treading softly by reason of some unknown wonder that possessed him, and lo, beneath the trees he saw the warm dusk full of sleeping forms, and some were twined each in the other’s arms, and some lay sleeping gently all alone, and Nuin stood and marvelled, scarce breathing (pg 232-233).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we conclude The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, discussing symbolism and creative editing.

This chapter is more of Christopher’s musings on how his father was positioning the editing of the book rather than the tale itself. Gilfanon only has a few pages, and the rest of his story remains unfinished. In a more accurate sense, this is an early iteration of the chapter in the Silmarillion “Of Men.”

The origin of Men for Tolkien was a difficult thing to tackle. Christopher tells us that there were four different iterations throughout the process of coming up with the concept. Tolkien ended up significantly cutting down the chapter to be what it eventually became, which was relatively uninspired and just about as long as Gilfanon’s tale. One has to wonder if the weight of the linchpin of his mythology was so great that the chapter says, “They wake,” and then moves on.

Gilfanon’s tale tells of one of the Dark Elves of Palisor, Nuin. Nuin is restless and curious about the world, so he ventures out to experience it and comes across a meadow that holds The Waters of Awakening and humans sleeping near it (described in the quote above).

Nuin then heads back home and tells a great wizard who ruled his people about the humans sleeping by the waters and “Then did Tû fall into fear of Manwë, nay even of Ilúvatar the Lord of All (pg 233).” because of this fear he turned to Morgoth, and learned deeper and darker magic from him.

From what Christopher tells us, each version of the story Tolkien worked on evolved, and eventually, Tû, the Wizard, was cut from the Silmarillion. Tolkien cut nearly all mention of the elves who went to Morgoth’s side from the main context. There are only a few mentions of thralls throughout the main storyline.

One has to wonder if this was Tolkien’s decision that the Elves themselves shouldn’t turn to the “dark side.” Even though the Noldor did some heinous things in Swan Haven, they ultimately did it out of a hatred that burned so deep for Morgoth’s blood that they wouldn’t let anyone stand in their way.

The inclusion of Tû, even if he is more of a fay creature than Elvish, creates issues with Tolkien’s history. So he took the name Tû out of the book to keep the Elvish lines as “pure” as possible, but the character of Tû is still in the book, AND I believe he plays a much larger part.

Remember that Tû is described as a fay wizard, and the only wizards in the history of Eä were the Istari (of which Saruman and Gandalf were a part). The Istari were Maiar, otherwise known as lesser Valar. In general, they were servants to the Valar (in The Book of Lost Tales, many of them were the children of the Valar) and aided in bringing the will of Ilúvatar into being.

The Istari were sent to Middle-earth in the Second Age to assist the people of that land in their fight against Sauron. They could turn into a mist and travel vast distances to reach their destination – something Sauron did after the Drowning of Númenor.

So this early Wizard trained in the dark arts by Morgoth must be an earlier version of Sauron himself. Sauron, after all, assisted the Elves in the creation of the Rings of Power, was known to be a wizard himself, and eventually picked up Morgoth’s mantle when the Dark Lord was locked behind the Door of Night.

The other exciting portion of the quote I’d like to discuss before closing thoughts is the mention of Nightingales and the Coming of Man in the opening quote.

Nightingales generally have a long history of symbolism, more specifically revolving around creativity, nature’s purity, or a muse. All of these aspects center around virtue and goodness.

Tolkien is using the nightingale song to indicate a more artistic and virtuous age because when Nuin followed the song, he came across the sleeping children by the Waters of Awakening.

Tolkien’s tale is ultimately (as we’ve covered many, many times) about Man (read that as Humans), so everything we have read thus far has been pre-history, which is also why Christopher separated The Book of Lost Tales into a part 1 and a part 2. Part 1 is about how the world became what it was. Now that we have humans, Part 2 is about the rest of the first age and carries what Christopher calls “all the best stories.”

So the nightingale indicates to the fay and the Eldar (Gnomes in The Book of Lost Tales) that there will be a shift in the world, and they will no longer be the focal point. This also spooks Nuin because, at the moment, by the Waters, he sees that his time will come to a close eventually, even though he’s immortal. The world was not built for him but for the new creatures just now waking into the world.

Join me next week as we have some final thoughts on The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, before jumping into The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, the week after!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1, The Hiding of Valinor

“‘Lo, all the world is grown clear as the courtyards of the Gods, straight to walk upon as are the avenues of Vansamírin or the terraces of Kôr; and Valinor no longer is safe, for Melko hates us without ceasing, and he holds the world without and many and wild are his allies there’ – and herein in their hearts they numbered even the Noldoli, and wronged them in their thought unwittingly, nor did they forget Men, against whom Melko had lied of old. Indeed in the joy of the last burgeoning of the Trees and the great and glad labour of that fashioning of ships the fear of Melko had been laid aside, and the bitterness of those last evil days and of the Gnome-folk’s flight was fallen into slumber – but now when Valinor had peace once more and its lands and gardens were mended of their hurts memory awoke their anger and their grief again (pg 207-208).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we reveal the cowardice of the Valar, the mystical side of Tolkien, and an overcorrection I’m sure everyone will be glad removed!

The tale of The Hiding of Valinor is connected intrinsically to the Tale of the Sun and the Moon, and, as it’s told in The Book of Lost Tales, seems to be an aside as the end of that chapter.

Vairë continues telling the tale of the history of the world to Eriol and quickly reveals that the Valar had become cowards in their efforts to protect their own little space of the world:

“The most of the Valar moreover were fain of their ancient ease and desired only peace, wishing neither rumour of Melko and his violence nor murmur of the restless Gnomes to come ever again among them to disturb their happiness; and for such reasons they also clamoured for the concealment of the land (pg 208).”

The Valar were tired of strife. They believed their creation was to create beauty and harmony; that is all they wanted to see.

Events like the Elves’ slaughter at the Haven of Swans and Melkor’s revolt against his kin caused the Valar to throw a temper tantrum and close their door against anything they felt uncouth. The sad aspect of this is that they created the world, so, in essence, the Valar are embarrassed that the things they made (except for Melkor) could be capable of such horrors that they want to cover their eyes on the issues.

Tolkien even calls them out in the voice of Vairë:

“Now Lórien and Vána led the Gods and Aulë lent his skill and Tulkas his strength, and the Valar went not at that time forth to conquer Melko, and the greatest ruth was that to them thereafter, and yet is; for the great glory of the Valar by reason of that error came not to its fullness in many ages of the Earth, and still doth the world await it (pg 209).”

It was cowardice and childishness that caused them to close off Valinor, nothing more. They wanted to believe their world was perfect and decided to disregard the rest of the world and let the Eldar (Gnomes in this [early] version) deal with a god themselves (Melkor).

This belief is the true folly of the Valar because they, with the help of the one creator Ilúvatar, were the only ones who could stop Melkor. And they did so in such a cosmically horrific way that Lovecraft would be proud.

At the beginning of this book, Tolkien mentions a bridge to the Dream World, built on rainbows (many of our beloved pets know about this rainbow bridge). This bridge, called Olórë Mallë (The Path of Dreams), was built at this point in Valinor’s history when the Valar were trying to hide the island, but they also understood that they might need to get in and out of the land. At this time, as they tried to build in their protections from all sides, they created The Door of Night, a decidedly Lovecraftian concept.

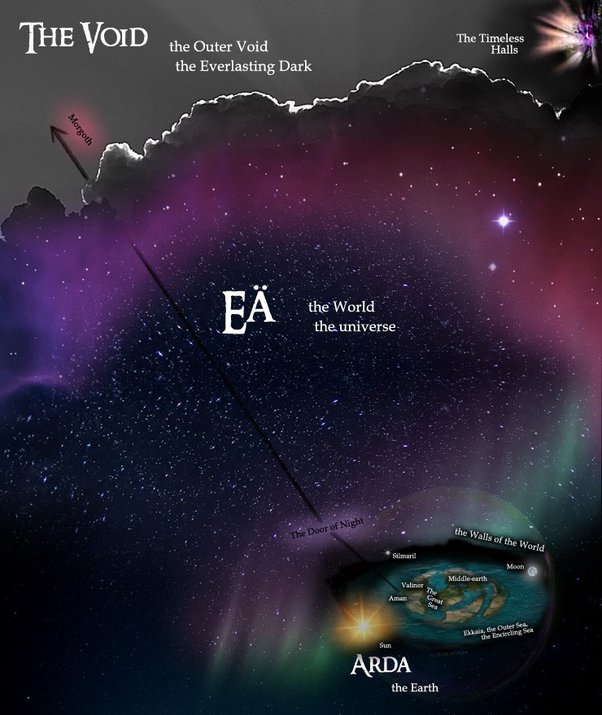

“they drew to the Wall of Things, and there they made the Door of Night (Moritarnon or Tarn Fui as the Eldar name it in thier tongues). There it still stands, utterly black and huge against the deep-blue walls. It’s pillard are of the mightiest basalt and its lintel likewise, but great dragons of black stone are carved thereon, and shadowy smoke pours slowly from their jaws. Gates it has unbreakable, and none know how they were made or set, for the last secret of the Gods; and not the onset of the world will force that door, which opens to a mystic world alone. That word Urwendi only knows and Manwë who spake it to her; for beyond the Door of Night is the outer dark, and he who passes therethrough may escape the world and death and hear things not yet for the ears of Earth-dwellers, and this may not be (pag 216).”

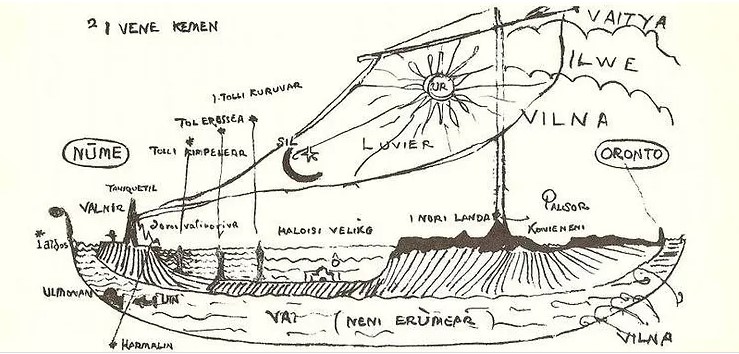

Ok, there is a lot to break down there. The world Tolkien built to this point (called Eä, otherwise known as Earth) was constructed on a vast ocean named Fui, which had outer and inner waters. The entirety of the world was built upon the internal waters, and the only Vala who even visited the extreme seas was Ulmo because he was the Valar in charge of water.

Even heaven and hell (called Vefántur and Fui, named after the Vala who created them) were contained within the inner waters. The outer waters were what was mentioned in the quote above (“for beyond the Door of Night is the outer dark, and he who passes therethrough may escape the world and death and hear things not yet for the ears of Earth-dwellers.”), which is a very Lovecraftian concept.

The concepts and creatures are so profound, beyond anything our minds can imagine, that no earthly being would be able to comprehend them. As far as I know, the only person who ever went beyond the Door of Night was when Ilúvatar and the Valar defeated Melkor, which ended the First Age, and imprisoned Melkor on the other side of the Door of Night, shunning him into the vacuum for eternity.

It seems like a fitting end for the Dark Lord of the first age, but Melkor was not as evil as even his apprentice, Sauron. What if Melkor ever got a chance to come back from the other side of the Door of Night, gaining all the terrible knowledge and madness in the outer dark? Then. Then he would genuinely be a Dark Lord to be reckoned with.

Join me next week for some closing thoughts on “The Hiding of Valinor!”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Tale of the Sun and the Moon

“Then there was silence that Manwë might speak, and he said: ‘Behold O my people, a time of darkness has come upon us, and yet I have it in mind that this is not without the desire of Ilúvatar. For the Gods had well-nigh forgot the world that lies without expectant of better days, and of Men, Ilúvatar’s younger sons that soon must come. Now therefore are teh Trees withered that so filled our land with loveliness and our hearts with mirth that wider desires came not into them, and so behold, we must turn now our thoughts to new devices whereby light may be shed upon both the world without and Valinor within (pg 181).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we get back into Tolkien’s religious background as we cover the Tale of the Moon and the Sun.

We’ve come to a point in the story where Melkor has killed the Trees of Valinor, and the Noldor killed many of their kin to steal ships to chase Melkor to Middle Earth.

The Vala faced the difficulty of what they should do. Melkor had left Valinor in darkness, and the trees were dead. What should their first action be? To go after Melkor and imprison him again, or try to figure out how to bring light back to Valinor.

The Spoke to Sorontur (who later became Thorondor), the King of Manwë’s eagles, and asked him to spy on Morgoth.

“…he tells how Melko is now broken into the world and many evil spirits are gathered to him: ‘but,’ quoth he, ‘methinks never more will Utumna open unto him, and already is he busy making himself new dwellings in that region of the North where stand the Iron Mountains very high and terrible to see (pg 176).'”

So the Valar doesn’t have to worry about Melkor for the time being because he will be spending all his time trying to make a home for himself. After hearing the Eagle’s report, it’s their opinion that Melkor will not be returning to Valinor, so he is now the Noldor’s problem, which they deserve because of the transgressions they laid on their fellow kin.

So that brings them back to their other issue. How do they deal with the loss of the light of Valinor? They decide that they must build a great ship and use the remainder of the light of the Trees, and this new ship can be like the stars, but it will travel the sky and light Valinor once again.

The prospect of the ship is exciting because it calls to mind the Greek God Helios, who rode a great chariot across the sky, and that is how the sun was to rise and set. Remember that Tolkien’s ultimate work was to create new mythos and mythology for England because Spencer’s work was sub-par (to Tolkien). This ship across the sky, built by gods, was a way that he could make things unique enough to fit within his landscape of fantasy. He even had a reason for the ship to rise and set:

“Now Manwë designed the course of the ship of light to be between the East and West, for Melko held the North and Ungweliant the South, whereas in the West was Valinor and the blessed realms, and in the East great regions of dark lands that craved for light (pg 182).”

But while they built this idea, he collected mythology from other areas and brought it into his ethos. Eventually, the ship was a failure. The downfall shows that Tolkien believed he was writing the ultimate mythology because the portion he took from another culture ultimately failed.

The Vala went back to Yavanna, who had created the Trees in the first place, but she had run through the energy needed. She poured everything she had into the trees, but it was Vána (another Valar who only appears in these early iterations) who made the most significant difference:

“Now was the time of faintest hope and darkness most profound fallen on Valinor that was ever yet; and still did Vána weep, and she twined her golden hair about the bole of Laurelin and her tears dropped softly at its roots; and even where her first tears fell a shoot sprang from Laurelin, and it budded, and the buds were all of gold, and there came light therefrom like a ray of sunlight beneath a cloud (pg 184).”

The tears of love brought Laurelin back to life enough to get those sprouts. “One flower there was however greater than the others, more shining, and more richly golden, and it swayed to the winds but fell not; and it grew, and as it grew of it’s own radient warmth it fructified (pg 185).”

The fruit that grew from the tree of Laurelin grew from tears, death, and rebirth. This fruit was, for Tolkien, his introduction to the Christian ideal of the Fruit of Knowledge. Still, instead of one of the Valar eating it and causing sin, the sin has already been created. The knowledge of death, destruction, jealousy, and Hubris has already taken hold of the peoples of Middle-earth because of Tolkien’s fallen Angel Melkor.

“Even as they dropped to earth the fruit waxed wonderfully, for all the sap and radience of the dying Tree were in it, and the juices of that fruit were like quivering flames of amber and of red and its pips like shining gold, but it’s rind was of a perfect lucency smooth as a glass whose nature is transfused with gold and therethrough the moving of its juices could be seen within like throbbing furnace-fires (pg 185).”

The Valar had found the fruit of knowledge that could shine the light on the land and destroy the darkness. The fruit knew what came before, and its sole meaning was to shine the morning so that others didn’t have to carry the burden of its dark understanding.

Join me next week as we complete the Tale of the Sun and the Moon.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Darkening of Valinor

“Now Melko having despoiled the Noldoli and brought sorrow and confusion into the realm of Valinor through less of that hoard than aforetime, having now conceived a darker and deeper plan of aggrandisement; therefore seeing the lust of Ungwë’s eyes he offers her all that hoard, saving only the three Silmarils, if she will abet him in his new design (pg 152).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we’re going to dive into the philosophy of Tolkien’s world through the events of The Darkening of Valinor.

We’ve discussed it before, but Tolkien relied heavily on his Christian background while creating this mythology. He wanted something new and unique for England, and as we know, mythologies are all origin stories.

The people of Middle-earth (Elves, Men, Dwarves, etc.) are all iterations of our evolution, and it shows from the beginning of The Book of Lost Tales that Tolkien intended for Middle-earth to be a precursor to Earth (he even calls it Eä in the Silmarillion).

Because this is mythology, Tolkien brings his version of the afterlife and the angels he introduces to the world. Melkor, who is Tolkien’s version of Satan, is ostracized for stealing the Eldar gems and Silmarils. Cast out of Heaven as it were:

“Now these great advocates moved the council with their words, so that in the end it is Manwë’s doom that word he sent back to Melko rejecting him and his words and outlawing him and all his followers from Valinor for ever (pg 148).”

But it was still during this period that Melkor was mischievous, but he had not transitioned to evil yet, even after being cast out of Valinor. So instead, he spent his time trying to create chaos using his subversive words:

“In sooth it is a matter for great wonder, the subtle cunning of Melko – for in those wild words who shall say that there lurked not a sting of the minutest truth, nor fail to marvel seeing the very words of Melko pouring from Fëanor his foe, who knew not nor remembered whence was the fountain of these thoughts; yet perchance the [?outmost] origin of these sad things was before Melko himself, and such things must be – and the mystery of the jealousy of Elves and Men is an unsolved riddle, one of the sorrows at the world’s dim roots (pg 151).”

The great deceiver has been created out of jealousy and anger for these beings of Middle-earth, believing that they were given more than their fair share and his own acts were ruined from the beginning of the Music of the Ainur.

But what did the Elves do? Was there anything they received that made anything Melkor did excusable?

“And at the same hour riders were sent to Kôr and to Sirnúmen summoning the Elves, for it was guessed that this matter touched them near (pg 147).”

It was nothing that they did, but the fact that the Valar treated them as equals to the Valar and Melkor’s slights against them weren’t considered pranks he felt they were, so his anger grew.

They were also allowed to be near their loved ones even after death. Elves were given the gift of immortality but can still be killed by disease or blade. But where do their spirits go when they die? Remember that this is a Christian-centric mythology, so Tolkien built an afterlife.

Called Vê after the Valar who created it, the afterlife on Middle-earth is contained within and around Valinor. This early conception (nearly cut entirely from The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings) was that Vê was a separate area of Valinor, slightly above and below it but still present, almost like a spirit world that contained the consciousness of the dead.

This region was all about, and the Eldar cannot commune with their deceased, but they continue to live close to them, and their spirit remains in Valinor.

“Silpion is gleaming in that hour, and ere it wanes the first lament for the dead that was heard in Valinor rises from that rocky vale, for Fëanor laments the death of Bruithwir; and many Gnomes beside find that the spirits of their dead have winged their way to Vê (pg 146).”

Melkor is jealous that the Elves can be so close to their dead ancestors, but he also doesn’t fully comprehend what being dead means because he is a Valar and eternal. He sees these beings going off to a different portion of Valinor and is upset because he thought he found a way to create distress amongst them by killing one of them. He doesn’t realize that he made a fire in the Eldar that would never wane.

“‘Yea, but who shall give us back the joyous heart without which works of lovliness and magic cannot be? – and Bruithwir is dead, and my heart also (pg 149).'”

Melkor schemed and stewed in his frustration and anger, feeling that even with his theft and his killing of Fëanor’s father, the first death of an Eldar (whom Tolkien was still calling Gnomes in this early version), there was nothing he could do to prove his worth, so his worth turned to evil. His music was dissonant and didn’t follow the themes of the other Valar, and he was looked down upon for that and cast aside. He pulled pranks that caused the other Valar to imprison him. All the while, his anger, and distrust grew until he did the ultimate act, which caused his to turn to true evil: He partnered with Ungoliant (the giant spider queen and mother of Shelob) and killed Silpion and Laurelin, the Trees which gave light to Valinor.

“Thus was it that unmarked Melko and the Spider of Night reached the roots of Laurelin, and Melko summoning his godlike might thrust a sword into its beauteous stock, and the firey radiance that spouted forth assuredly had consumed him even as it did his sword, had not Gloomweaver (Ungoliant) cast herself down and lapped it thirstily, plying even her lips to the wound in the tree’s bark and sucking away it’s life and strength (pg 153).”

Melkor had finally become evil. He had turned against the Valar and what brought the world light and gave that power to evil creatures.

The Valar and Eldar cried out against Melkor for being cruel, but the tragedy of Melkor’s story was that he never had a choice.

Early in the mythology of this world, Tolkien tells us that Ilúvatar had a theme and a story for eternity, which the Valar were not privy to. Instead, they thought their music and their acts were meant to create only beauty and love.

Ilúvatar, however, knew that to have true meaning, there must be pain, conflict, and evil. Otherwise, all the world’s good would disappear and become mundane. So Ilúvatar created Melkor, knowing what he was going to become. He made Melkor evil in the world.

Melkor was born to suffer. Melkor was born never to know love. Melkor was created to become a creature that others could be tricked into feeling sorry for, and thus trade the light of the Valar for the Darkness of the Dark Lord.

Join me next week as we cover “The Flight off the Noldoli!”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Theft of Melko

“Listen then, O Eriol, if thou wouldst [know] how it came that the loveliness of Valinor was abated, or the Elves might ever be constrained to leave the shores of Eldamar. It may well be that you know already that Melko dwelt in Valmar as a servant in the house of Tulkas in those days of the joy of the Eldalië; there did he nurse his hatred of the Gods, and his consuming jealousy of the Eldar, but it was his lust for the beauty of the gems for all his feigned indifference that in the end overbore his patience and caused him to design deep and evilly (pg 140).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we kick off the events which changed the face of Eä and how those events changed from the original writings to the publication of The Silmarillion.

This chapter, more than anything before, indeed shows how Tolkien’s ideas shifted over time. The designs of Melkor and Sauron are so interwoven in this early work that the distinction between them when he finally got to writing about the later ages must have been muddled.

There are many instances in this chapter where Melkor is subversive, getting the Elves to believe in him and forsake the Valar. Melkor did some of this later in The Silmarillion, but most of his actions were facilitated out of anger and jealousy. Melkor is Tolkien’s iteration of Lucifer, the fallen angel who once desired to do positive things, whereas Sauron is evil when his visage hits the page.

In the beginning, Melkor was one of the Valar. He was around before the world was created, and indeed, it was through the music of the Valar (called Ainur) that the world was created. Melkor was disparaged early on because his music was discordant and didn’t match up with the music of the other Valar. His anger grew like a young child playing off-key in a band. The other Valar were upset with him because their music had themes, and with Melkor creating the music the way he was, the themes had strange off notes, making unintended things.

You may have heard the phrase: “There are older and fouler things than Orcs in the deep places of the world.” These “fouler things” were created from this discordant music as the world was being made. Thus, they are deep within the world, almost Cthulhu-godlike creatures born into the depths of the world, undescribed but horrible to behold.

Because of this mistake, The Valar treated Melkor differently. Then when the Eldar awoke, he perceived them as being favored over himself, so he folded in on his own conscious and acted out of hate and jealousy.

Sauron, on the other hand, was Melkor’s servant (Maiar), and it is possible that Sauron saw what was happening to Melkor and decided to fight against the world because of the treatment his master and Dark Lord received. However, he wasn’t written that way. Instead, Sauron wanted to rule the world from the moment he was created and was very subversive in his tactics.

In this chapter, Tolkien blends the two different personalities. First, Melkor tries to get into Fëanor’s head and turn him against the Valar and the other Noldor; however, in The Silmarillion, Fëanor is too clever, and Melkor attempts to corrupt Fëanor causes the Eldar to hate The Dark Lord eternally. In The Book of Lost Tales, Melkor ends up with different motivations entirely:

“At length so great became his care that he took counsel with Fëanor, and even with Inwë and Ellu Melemno (who then led the Solosimpi), and took their rede that Manwë himself be told the dark ways of Melko (pg 141).”

Melkor assists Fëanor in creating the Silmarils, much like Sauron helped Celebrimbor create the Rings of Power.

Tolkien doesn’t specifically call this out as a motivation for stealing the gems back; in fact, they seem to be an afterthought:

“With his own hand indeed he slew Bruithwir father of Fëanor, and bursting into that rocky house that he defended laid hands upon those most glorious gems, even the Silmarils, shut in a casket of ivory (pg 145).”

Melkor was after the gems because he wanted to take the Eldar’s possessions and knew they considered their jewels highly valuable.

The Silmarils themselves were still of high quality because they came from the starlight of Aulë’s forge, but in the writing of this chapter, it feels as though they were an afterthought for Tolkien.

Christopher (Tolkien’s son and editor) contends that Melkor is only there to steal the gems, and it wasn’t until later iterations of the story that the Silmarils became more critical.

Thinking like a writer, Tolkien always intended to have the Silmarils be necessary, but not because an Elf made them (or Gnome in this early version). I think his intent in the Book of Lost Tales was to have the Silmarils be so crucial because of the influence of the Valar. Still, as he progressed in history, he realized that it was the Eldar’s story, not the Valar’s, so he adjusted it to have Fëanor be of an original heritage (he became Finwë’s son instead of the unknown Bruithwir) and make the world-breaking Silmarils.

Later, when he had beings of a short life (Men and Hobbits), and everyday events played a much more critical role in their life, he adjusted the story to have Sauron be involved in creating the Rings of Power. It is a different story, and there are other stakes, not to mention that Sauron is a Maiar, not a Valar; thus, his power level isn’t as complete. The gods might not come down from the heavens to take care of someone lesser than them, where Melkor was one of their own and thus their responsibility.

While reading this book, you must remember that it was never meant to be published. Christopher Tolkien compiled the Book of Lost Tales from notebooks and scraps of paper. It was the Silmarillion that Tolkien himself meant to publish. Christopher published The Book of Lost Tales for the same reason I’m writing a blog about it; people who love Lord of the Rings might want to know the evolution of the story to what it eventually became.

Join me next week as we take a break from the Book of Lost Tales! I will give an update on current and future projects and cover some very exciting things to come!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales part 1, The Making of Kôr

“Now therefore do the God bid the Elves build a dwelling, and Aulëaided them in that, but Ulmo fares back to the Lonely Island, and lo! it stands now upon a pillar of rock upon the seas’ floor, and Ossë fares about it in a foam of business anchoring all the scattered islands of his domain fast to the ocean-bed (pg 121).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we get a more significant image of who the Elves, and each clan of Elves, were.

The first thing we have to cover is the making of Kôr:

“Behold there is a low place in that ring of mountains that guards Valinor, and there the shining of the Trees steals through from the plain beyond and guilds the dark waters of the bay of Arvalin, but a great beach of finest sand, golden in the blaze of Laurelin, white in the light of Silpion, runs inland there, where in the trouble of the ancient seas a shadowy arm of water had groped in toward Valinor, but now there is only a slender water fringed with white.At the head of this long creek there stands a lonely hill which gazes at the loftier mountains…Here was the place that those fair Elves bethought them to dwell, and the Gods named that hill Kôr by reason of its roundness and it’s smoothness (pg 122).”

This soft hill became the home of the Noldori Elves and the Teleri Elves. But, unfortunately, the only group that wanted to live in a new space were the Solosimpi Elves, the favorite of Ulmo the sea Valar. So the Solosimpi stayed out on Tol Eressëa, a place that “is held neither of the Outer lands or of the Great Lands where Men after roamed (pg 125).”

The Solosimpi became the favorite of Ulmo because they decided to stay away from Valinor. He taught them music and sea lore and lived in general harmony. They lived in the caves by the sea in connection with all other living creatures of the land. Valinor, at the time, had very few creatures (primarily sprites and fae), so the Solosimpi were better equipped to deal with strife because they could see the circle of life in motion. They could see creatures being hunted and killed so that others could live. They had worldly wisdom.

They also came to love birds for their beauty, simplicity, and grace. Ossë (Ulmo’s fellow water Valar, who in The Silmarillion became a Maiar), wanted to stoke this love, but he also didn’t like the Solosimpi to be estranged from their kin; “For lo! there Teleri and Noldoli complain much to Manwë of the separation of the Solosimpi, and the Gods desire them to be drawn to Valinor; but Ulmo cannot yet think of any device save by help of Ossë and the Oarni, and will not be humbled to this (pg 124).”

Yet again, we see Ulmo’s jealousy. The reason for the change in character between this book and The Silmarillion must be the change from the lesser Valar being siblings and children of the Valar to becoming a Maiar. This Sea-change of the power dynamics was twofold; 1. to make it a more straightforward narrative and include fewer names (which anyone who read The Silmarillion would attest to), and 2. To make the motivations of the Valar more clear. Melkor is the one who is supposed to be jealous and to take out that jealousy on the Eldar, not the other Valar. If they held these same jealousies, then both the Valar would be diminished, and Melkor wouldn’t be as much of a “Dark Lord” because others with his power level feel the same way.

Still, it is interesting to see that the transition, and the reality, of the concept of anger and jealousy in The Book of Lost Tales is much more feasible than in The Silmarillion. Somehow the events in this book make the Valar, just that much more relatable.

Going back to the quote above, Ulmo was not to be outdone by any other Valar, so he facilitated “the first hewing of trees that was done in the world outside of Valinor (pg 124).”

He partnered with Aulë, and together they “sawn wood of pine and oak make great vessels like to the bodies of swans, and these he covers with the bark of silver birches, or…with gathered feathers of the oily plumage of Ossë’s birds. (pg 124)”

Remember that the Solosimpi were in the later versions of the Teleri Elves, so this is the first iteration of the Lothlórien “Swan Shaped Barge,” which we also briefly glimpse Galadriel on in The Lord of the Rings.

The Noldor seemed to be flourishing on their island, and with the assistance of the Valar, each tribe seemed to specialize in different practices. Unfortunately, this eventually ended the Golden Age of the Eldar in Tol Eressëa (Kôr).

“Then arose Fëanor of the Noldoli and fared to the Solosimpi and begged a great pearl, and he got moreover an urn full of the most luminous phosphor-light gathered of foam in dark places, and with these he came home, and he took all the other gems and did gather their glint by the light of white lamps and silver candles, and he took the sheen of pearls and the faint half-colours of opals, and he [bathed?] them in phosphorescence and the radient dew of Silpion, and but a single tiny drop of the light of Laurelin did he let fall therein, and giving all those magic lights a body to dwell in of such perfect glass as he alone could make nor even Aulë compass, so great was the slender dexterity of the fingers of Fëanor, he made a jewel… Then he made two more…he those jewels he called Silmarilli (pg 128).”

Fëanor, in this early iteration, is just an unnamed Noldor, not Finwë’s direct lineage, but he still creates the Silmarils, which starts all the events of the First Age in motion.