Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, pt 1, The Flight of the Noldoli

“Now tells the tale that as the Solosimpi wept and the Gods scoured all the plain of Valinor or sat despondent neath the ruined Trees a great age passed and it was one of gloom, and during that time the Gnome-folk suffered the very greatest evils and all the unkindliness of the world beset them. For some marched endlessly along that shore until Eldamar was dim and forgotten far behind, and wilder grew the ways and more impassable as it trended to the North, but the fleet coasted beside them not far out to sea and the shore-farers might often see them dimly in the gloom, for they fared but slowly in those sluggish waves (pg 166).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we delve into Tolkien’s storytelling process and understand why he wrote the book and where he wanted it to go.

We left off last week with the Darkening of Valinor and the betrayal of Melkor. As soon as we start this chapter, we find that Tolkien intended this chapter to be part of the events of The Darkening of Valinor. Christopher edited this into a separate chapter because he knew where the narrative would eventually lead.

“There is no break in Lindo’s narrative, which continues on in the same hastily-pencilled form (and near this point passes to another similar notebook, clearly with no break in composition), but I have thought it convenient to introduce a new chapter, or a new ‘Tale’, here, again taking the title from the cover of the book (pg 164).”

Christopher segregated this chapter because, as it’s written, it’s missing some of the weight that goes into the betrayal and exile of the Noldor Elves.

The Book of Lost Tales tells the story of Valinor and the Valar, but the story at the core of The Silmarillion is about the Elves. They were the ones who created humanity and life in the world. Where the Valar did the act of making the world with their song, the Eldar (and later on Humans) created culture and meaning, which gave Middle-earth purpose.

In his development of The Book of Lost Tales (only called this because that’s what Christopher called it), Tolkien wanted to understand what these Angels were like; what their personalities were, how they treated each other, and how they treated the “Children.”

I’m not convinced that these books (The Book of Lost Tales, Vol 1 and 2) were ever meant to see the light of day, especially since Christopher admits that the material comes from notebooks and scrap paper, but what is impressive about them is that we get to see the development of the world from the ground up.

Tolkien was a plotter and wanted his mythology (his fairy tale) to be as complete as possible. So he worked for years (first putting pen to paper during his time in the trenches of the Great War), making sure that this Magnum Opus was precisely how he wanted it.

When it comes to this chapter, Tolkien came to realize that the Noldor was not severe enough. The fact that Melkor stole some gems and then was made to return some of them was not enough. The fact that Melkor killed Fëanor’s father, the first death of an Eldar ever, was not enough. He needed the Eldar to have their arc unique from the Valar and much more interesting than the Valar because stories where gods are the centerpiece just aren’t as interesting. Tolkien himself knew this, and that’s why his two “novels” (The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings) had simple people as the main protagonists. Life and art are just more enjoyable when you have to overcome obstacles.

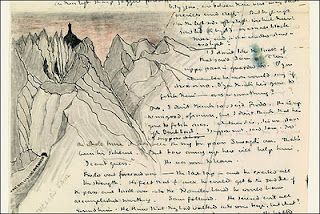

So Tolkien took a look at his early flight of the Noldor and made a note:

“At the top of the manuscript page and fairly clearly referring to Fëanor’s words my father wrote: ‘Increase the element of the desire for the Silmarils’. Another note refers to the section of the narrative that begins here and says that it ‘wants a lot of revision: the [?thirst ?lust] for jewels – especially for the sacred Silmarils – wants emphasizing. And the all-important battle of Cópas Alqaluntë where the Gnomes slew the Solosimpi must be inserted (pg 169).'”

Cópas Alqaluntë is the core of why Christopher separated this chapter. The Noldor killing their kin to steal their boats to seek vengeance from Melkor doesn’t hit as hard if it is part of the story of the Darkening of Valinor.

Tolkien needed to create a new chapter and new motivations (which he did in The Silmarillion) to make their actions more impactful. This singular act creates a rift between the Eldar and the Valar, and Fëanor’s never-ending rage drives the narrative for the remainder of the Age.

His firey and charismatic personality gave the Noldori Elves something to rally behind, and the fact that he created the Silmarils himself (and that they held the light of the now-dead Trees of Valinor) raised the stakes much more.

Tolkien turned his thoughts bloody and created a visceral battle where the Noldor turned against their brethren in a brutal and bloody way, which was not present in this earlier version. This act is what damned the Noldor for the rest of time:

“Songs name that dwelling the Tents of Murmuring, for there arose much lamentation and regret, and many blamed Fëanor bitterly, as indeed was just, yet few deserted the host for they suspected that there was no welcome ever again for them back to Valinor – and this some few who sought to return indeed found, though this entereth not into this tale (pg 168).”

Join me next week as we delve into “The Tale of the Sun and the Moon.”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, The Darkening of Valinor

“Now Melko having despoiled the Noldoli and brought sorrow and confusion into the realm of Valinor through less of that hoard than aforetime, having now conceived a darker and deeper plan of aggrandisement; therefore seeing the lust of Ungwë’s eyes he offers her all that hoard, saving only the three Silmarils, if she will abet him in his new design (pg 152).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we’re going to dive into the philosophy of Tolkien’s world through the events of The Darkening of Valinor.

We’ve discussed it before, but Tolkien relied heavily on his Christian background while creating this mythology. He wanted something new and unique for England, and as we know, mythologies are all origin stories.

The people of Middle-earth (Elves, Men, Dwarves, etc.) are all iterations of our evolution, and it shows from the beginning of The Book of Lost Tales that Tolkien intended for Middle-earth to be a precursor to Earth (he even calls it Eä in the Silmarillion).

Because this is mythology, Tolkien brings his version of the afterlife and the angels he introduces to the world. Melkor, who is Tolkien’s version of Satan, is ostracized for stealing the Eldar gems and Silmarils. Cast out of Heaven as it were:

“Now these great advocates moved the council with their words, so that in the end it is Manwë’s doom that word he sent back to Melko rejecting him and his words and outlawing him and all his followers from Valinor for ever (pg 148).”

But it was still during this period that Melkor was mischievous, but he had not transitioned to evil yet, even after being cast out of Valinor. So instead, he spent his time trying to create chaos using his subversive words:

“In sooth it is a matter for great wonder, the subtle cunning of Melko – for in those wild words who shall say that there lurked not a sting of the minutest truth, nor fail to marvel seeing the very words of Melko pouring from Fëanor his foe, who knew not nor remembered whence was the fountain of these thoughts; yet perchance the [?outmost] origin of these sad things was before Melko himself, and such things must be – and the mystery of the jealousy of Elves and Men is an unsolved riddle, one of the sorrows at the world’s dim roots (pg 151).”

The great deceiver has been created out of jealousy and anger for these beings of Middle-earth, believing that they were given more than their fair share and his own acts were ruined from the beginning of the Music of the Ainur.

But what did the Elves do? Was there anything they received that made anything Melkor did excusable?

“And at the same hour riders were sent to Kôr and to Sirnúmen summoning the Elves, for it was guessed that this matter touched them near (pg 147).”

It was nothing that they did, but the fact that the Valar treated them as equals to the Valar and Melkor’s slights against them weren’t considered pranks he felt they were, so his anger grew.

They were also allowed to be near their loved ones even after death. Elves were given the gift of immortality but can still be killed by disease or blade. But where do their spirits go when they die? Remember that this is a Christian-centric mythology, so Tolkien built an afterlife.

Called Vê after the Valar who created it, the afterlife on Middle-earth is contained within and around Valinor. This early conception (nearly cut entirely from The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings) was that Vê was a separate area of Valinor, slightly above and below it but still present, almost like a spirit world that contained the consciousness of the dead.

This region was all about, and the Eldar cannot commune with their deceased, but they continue to live close to them, and their spirit remains in Valinor.

“Silpion is gleaming in that hour, and ere it wanes the first lament for the dead that was heard in Valinor rises from that rocky vale, for Fëanor laments the death of Bruithwir; and many Gnomes beside find that the spirits of their dead have winged their way to Vê (pg 146).”

Melkor is jealous that the Elves can be so close to their dead ancestors, but he also doesn’t fully comprehend what being dead means because he is a Valar and eternal. He sees these beings going off to a different portion of Valinor and is upset because he thought he found a way to create distress amongst them by killing one of them. He doesn’t realize that he made a fire in the Eldar that would never wane.

“‘Yea, but who shall give us back the joyous heart without which works of lovliness and magic cannot be? – and Bruithwir is dead, and my heart also (pg 149).'”

Melkor schemed and stewed in his frustration and anger, feeling that even with his theft and his killing of Fëanor’s father, the first death of an Eldar (whom Tolkien was still calling Gnomes in this early version), there was nothing he could do to prove his worth, so his worth turned to evil. His music was dissonant and didn’t follow the themes of the other Valar, and he was looked down upon for that and cast aside. He pulled pranks that caused the other Valar to imprison him. All the while, his anger, and distrust grew until he did the ultimate act, which caused his to turn to true evil: He partnered with Ungoliant (the giant spider queen and mother of Shelob) and killed Silpion and Laurelin, the Trees which gave light to Valinor.

“Thus was it that unmarked Melko and the Spider of Night reached the roots of Laurelin, and Melko summoning his godlike might thrust a sword into its beauteous stock, and the firey radiance that spouted forth assuredly had consumed him even as it did his sword, had not Gloomweaver (Ungoliant) cast herself down and lapped it thirstily, plying even her lips to the wound in the tree’s bark and sucking away it’s life and strength (pg 153).”

Melkor had finally become evil. He had turned against the Valar and what brought the world light and gave that power to evil creatures.

The Valar and Eldar cried out against Melkor for being cruel, but the tragedy of Melkor’s story was that he never had a choice.

Early in the mythology of this world, Tolkien tells us that Ilúvatar had a theme and a story for eternity, which the Valar were not privy to. Instead, they thought their music and their acts were meant to create only beauty and love.

Ilúvatar, however, knew that to have true meaning, there must be pain, conflict, and evil. Otherwise, all the world’s good would disappear and become mundane. So Ilúvatar created Melkor, knowing what he was going to become. He made Melkor evil in the world.

Melkor was born to suffer. Melkor was born never to know love. Melkor was created to become a creature that others could be tricked into feeling sorry for, and thus trade the light of the Valar for the Darkness of the Dark Lord.

Join me next week as we cover “The Flight off the Noldoli!”

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Silmarillion, Of the Ruin of Doriath, Part 2

“Thus it came to pass that when the Dwarves of Nogrod, returning from Menegroth with diminished host, came again to Sarn Athrad, they were assailed by unseen enemies; for as they climbed up Gelion’s banks burdened with the spoils of Doriath, suddenly all the woods were filled with the sound of elven-horns, and shafts sped upon them from every side. There very many of the Dwarves were slain in the first onset; but some escaping from the ambush held together, and feld eastwards towards the mountains. And as they climbed the long slopes beneath Mount Dolmed there came forth the Shephers of the Trees, and they drove the Dwarves into the shadowy woods of Ered Lindon: whence, it is said, came never one to climb the high passes that led to their homes.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we come back to the tragic conclusion of the Ruin of Doriath and understand how the races came to hate each other.

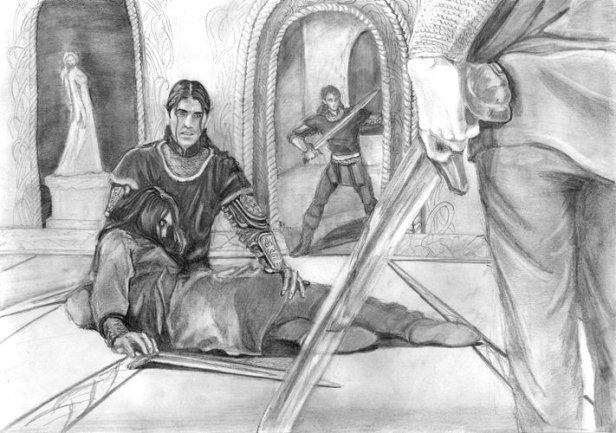

Last week we left off with the murder of King Thingol in his very chambers. The power of the Silmaril, which the Dwarves forged into Nauglamir, was too great and created envy that overrode their memory and senses. They were suddenly angry because they felt Thingol didn’t deserve Nauglamír, as it was a gift to Finrod made by the Dwarves. So when Thingol asked them to reforge it with the Silmaril, they did so without hesitation. Still, after giving it back, the absence of the light of Valinor made them regret their decision, so they struck Thingol down, took Nauglamír, and fled Menegroth.

But they were “pursued to the death as they sought the eastward road, and the Nauglamír was retaken, and brought back in bitter grief to Melian the Queen.” Her thoughts grew dark, “and she knew that her parting from Thingol was the forerunner of a great parting and that the doom of Doriath was drawing neigh.”

In her grief, her magic waned, and the Girdle protecting Doriath fell, “and Doriath lay open to its enemies.” So she gave Nauglamír, inlaid with the Silmaril, to Mablung and asked him to send word to Beren and Lúthien, then “she vanished out of Middle-earth, and passed to the land of the Valar beyond the western sea, to muse upon her sorrows in the gardens of Lórien, whence she came.“

Two dwarves escaped the attack on the murderers of Thingol, however, and went back to their kin in Nogrod. These Dwarves vowed vengeance and gathered a great host to march on Doriath, “and there befell a thing most grievous among the sorrowful deeds of the Elder Days.”

The Dwarves lost many of their kin in the battle in Menegroth, but they sacked the city; “ransacked and plundered.” Finally, they killed Mablung and took back Nauglamír and the Silmaril.

Word spread quickly of the terrible act the Dwarves perpetrated, and soon Beren and Lúthien heard of it. So Beren gathered his son Dior and a host of Green Wood Elves and went after the Dwarves; their confrontation is the opening passage of this essay.

They slaughtered the Dwarves, Beren himself killing the King of Nogrod. Then, finally, the Elves and Beren drowned the treasure of Menegroth in the river Ascar, all that is, but Nauglamír and the Silmaril.

Now the Silmaril was back in his hands, the item he fought so hard to win Lúthien’s hand in marriage by cutting it out of Morgoth’s crown. He took it to Lúthien, and she wore it for protection, and “it is said and sung that Lúthien wearing that necklace and that immortal jewel was the vision of greatest beauty and glory that has ever been outside realm of Valinor.”

Dior, Thingol’s heir, took it upon himself to bring the glory of Doriath back. So he brought his wife Nimloth, his boys Eluréd and Elurín, and his daughter Elwing to Menegroth, and there he became the new King of Doriath and raised a new kingdom there.

There, in Menegroth, Dior brought greatness back until one day a group of Green Elves came calling. They brought with them Nauglamír and the Silmaril. Proof that Beren and Lúthien, his parents, had passed from the world of Men and Elves. “But the wise have said that the Silmaril hastened their end, for the flame of the beauty of Lúthien as she wore it was too bright for mortal hands.“

Dior knew this, but the call of the Silmaril was too strong, so he began to wear it, and in doing so, the Silmaril called for another end of Doriath.

The Sons of Fëanor laid a new claim to the Silmaril and demanded that Dior relinquish the jewel. When he refused, “Celegorm stirred up his brothers to prepare an assault on Doriath.”

They fought a battle that all would remember. Celegorm, Curufin, and dark Caranthir all died by Dior’s hand, but they, in turn, killed the new king of Doriath and Dior’s wife, Nimloth. The “cruel servants of Celegorm” also took Dior’s boys Eluréd and Elurín and set them to be lost and starve in the woods. The only survivor of the household was Elwing, who was given Nauglamír, and fled to the sea at the mouth of the River Sirion.

“Thus Doriath was destroyed, and never rose again.”

The sons of Fëanor sought, all the way back when they were still in Valinor, to gain the three gems known as the Silmarils their father made. The light of the trees of Valinor infused within them gave a longing call to the life they once had lived. So they spent more time on Beleriand than they did in Valinor, pining for the gems which reminded them of the world they left behind.

The Murder of the King of Nogrod also had a lasting effect on the Dwarves, and because of their stubbornness was something their race never forgot, even though the whole war was pretty much their fault in the first place. Beyond that, the Elves have proven time and time again that they can’t trust anyone, not even their own kin.

I find it fascinating that the whole world was turned upside down because of these artifacts that were only sought because of their beauty. They were created to be an homage to the light of Valinor, and they became the destruction of Beleriand. The strange part about that is that they don’t hold any specific power; it’s just that they are beautiful, which shows the ignorant and selfish nature of the Elves. They are called the Children of Ilùvatar, and that is precisely how they act, like petulant children who can’t share.

Only two chapters are left, and one has to wonder where the Valar are. Will Melian inform them about how bad the infighting had gotten? How will Morgoth be handled? Where will Elwing and the Silmaril end up next?

Let’s find out next week as we dive into “Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.