Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Túrin’s first tragedy

“To ease his sorrow and the rage of his heart, that remembered always how Úrin and his folk had gone down in battle against Melko, Túrin was for ever ranging with the mosst warlike of the folk of Tinwelint far abroad, and long ere he was grown to first manhood he slew and took hurts in frays with the Orcs that prowled unceasingly upon the confines of the realm and were a menace to the Elves (pg 74).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we begin to learn a bit about Túrin and experience his first tragedy of character while trying to understand Tolkien’s purpose in the themes of this tale.

Tolkien spends much of his time in this early version of Turmabar, striving to show the differences between Men and Elves (the more Tolkien created, the less he described Elves as Gnomes. It seems like he started to think of Gnomes as anything fay-like, as the moniker became a catch-all). Men tended to be less unkempt, more creatures of passion, whereas Elves were much better groomed and stoic.

Through this time, Tolkien was still developing his story, language, world, and its peoples, and these lost tales were written as an exploratory first draft to get the world out of his head and onto paper, but, as evidenced by The Silmarillion, Tolkien was not happy with these early drafts. They lacked cohesion and a thematic goal.

An example of this is as follows: “Now Túrin lying continually in the woods and travailing in far and lonely places grew to be uncouth of raiment and wild of locks, and Orgol made jest of him whensoever the twain sat at the king’s board; but Túrin said never a word to his foolish jesting, and indeed at no time did he give much heed to words that were spoken to him, and the eyes beneath his shaggy brows oftentimes looked as to a great distance (pg75).”

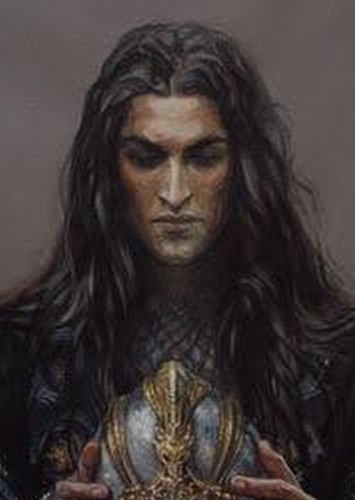

Túrin is a Man (as in every other Blind Read; read this as Human whenever capitalized), and Men are described as much more feral creatures. This classification was the original intent of Men, specifically because of Tolkien’s experiences in The Great War, he distrusted human instinct and saw humans as impetuous and violent creatures. Violent and feral is a very apt description of how Túrin (and almost every other Human in this story thus far) is described. He is animalistic; he “seemed to see far things and to listen to sounds of the woodland that others heard not (pg 75).” “He was moody (pg 75).”

One function of this could be because the majority of Men in these early stories that came from Hithlum were captured by Melko and held as thralls and slaves for many years, and Túrin (in The Book of Lost Tales, not The Silmarillion) is no exception, but more realistically Tolkien initially created Men this way because they were not born of the gods the way the Eldar were. Their lives are short; thus, they are much more emotional and prone to reaction because they need to feel the depths of emotion and experience much quicker than their immortal brethren.

This version of Turambar is much less tragic and much more vicious. Orgof, the Eldar we saw above who was a playground bully of Túrin, takes the place of Saeros. In the later Silmarillion version, Saeros is still a bully, but when Túrin finds him in the wilds, he turns the tide and strips Saeros naked, intending to embarrass the bully. Saeros, terrified, tries to jump a Fjord and falls to his death. This accidental death is the first event that makes Túrin an outlaw, but in this version, nearly everyone in Doriath sympathizes with Túrin and tries to get him to come back, but his conscience is what pushes him further into exile.

This earlier version is entirely different:

“Then a fierce anger born of his sore heart, and these words concerning the lady Mavwin blazed suddenly in Túrin’s breast so that he seized a heavy drinking vessel of gold that lay by his right hand and, unmindful of his strength, he cast it with great force in Orgof’s teeth, saying: ‘Stop thy mouth therewith, fool, and prate no more.’ But Orgof’s face was broken and he fell back with great weight, striking his head upon the stone of the floor and dragging upon him the table and all it’s vessels, and he spake nor prated again, for he was dead (pg 75).”

Túrin’s actions were murder in this earlier version. It was an act of a feral and impetuous being, as we should expect from any Human in these early tales of Tolkien.

To take that a step further and show the difference between Elves and Men, Tinwelint and his court show incredible understanding. “Yet they did not seek his harm, although he knew it not, for Tinwelint despite his grief and the ill deed pardoned him, and the most of his folk were with him in that, for Túrin had long held his peace or returned courtesy to the folly of Orgof (pg 76).”

Meanwhile, Túrin runs away and joins a group of people in the woods described as “wild spirits (pg76).” Again, Túrin is a Human and feeds into his animalistic tendencies. His emotions are so high that he cannot understand that there could be clemency for him in Doriath because he does not hold any for himself. His emotions again overpower him, and he runs off to the only place where he feels at home, in the forest with ruffians.

This kind of childish behavior is endemic to Men in early Tolkien, and it isn’t until the later versions (I believe The Silmarillion is either the Third or Fourth draft) that they begin to get more depth and character. The whole point of these stories evolved from being a general history of our world to actual ages of time, and this time was the Age of the Eldar. Tolkien’s main goal, however, was leading his fairy tale, through Eriol and The Cottage of Lost Play, to the fourth Age. The Age of Men.

Join me next week as we introduce one of The Silmarillion’s best characters, Beleg, and discover Túrin’s second tragic act.

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Turambar

“Now coming before that king they were received well for the memory of Úrin the Steadfast, and when also the king heard of the bond tween Úrin and Beren the One-handed and the plight of that lady Mavwin his heart became softened and he granted her desire, nor would he send Túrin away, but rather said he: ‘Son of Úrin, thou shalt dwell sweetly in my woodland court, nor even so as a retainer, but behold as a second child of mine shalt thou be, and all the wisdoms of Gwendheling and of myself shalt thou be taught (Pg 73).'”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we introduce Túrin and his tragedy while getting some commentary about Tolkien’s decision to create a story throughline instead of the history that the tale became.

Christopher begins this chapter by speaking of the timeframe of the writing itself and how his father wrote Turambar in the time between the original script of Tinúviel and the edits of that tale:

“There is also the fact that the rewritten Tinúviel was followed, at the same time of composition, by the first form of the ‘interlude’ in which Gilfanon appears, whereas at the beginning of Turambar there is reference to Ailios (who was replaced by Gilfanon) concluding the previous tale (pg 69).”

I bring this to your attention because of the profound changes Tolkien was making at the time and the apparent fact that Christopher missed when he made the assertion of Beren always being intended to be Eldar.

Ailios or Gilfanon said, shortly after his introduction, “‘Now all folk gathered here know that this is the story of Turambar and the Foalókë, and it is,’ said he, ‘a favourite tale among Men, and tells of very ancient days of that folk before the Battle of Tasarinan when first Men entered the dark vales of Hisilómë (pg 70).'”

Tolkien establishes almost immediately that this is a story about Men, not Gnomes or Elves, and it is only a few pages later that we get this passage:

“…but the deeds of Beren of the One Hand in the halls of Tinwelint were remembered still in Dor Lómin, wherefore it came into the heart of Mavwin, for lack of other council, to send Túrin her son to the court of Tinwelint, begging him to foster this orphan for the memory of Úrin and of Beren son of Egnor (pg 72).”

Here, we get a direct correlation between Beren and Úrin, one of which is a Man and the other is an Elf in the established setting. To go even further, in the opening quote of this essay, Tolkien states that Beren and Egnor were friends, and before this passage, in early Tolkien, there was no love lost between Elves and Men. This is the first instance of the earlier works where an Elf and a Man were friends.

I contend that this was an accident on Tolkien’s part because he was already beginning to think of Beren and Egnor as Men. After all, it fits the story so much better. There is even a passage where Egnor is “akin to Mavwin.” Egnor is Beren’s father, and Mavwin is Túrin’s mother, thereby stating that Egnor was, at the very minimum, a half-elf, but such things never existed in Tolkien. (You might remember Elros and Elrond, who were born half-elves; however, the Vala made them decide which side they were to fall on, and Elros became a man and founded the Númenóreans and Elrond became an Elf…and we know how that story ends)

Tolkien also brings back the Path of Dreams, or Olórë Mallë, to explain how Ailios (Gilfanon) knows these stories firsthand (there is a reference that he also knows the story of the fall of Gondolin: “and I knew it long ere I trod Olórë Mallë in the days before the fall of Gondolin (pg 70).” The more that I read of these Lost Tales, the more I understand why Tolkien took Gilfanon out of the story, and why he also took out the transitions.

Tolkien initially wanted these stories to flow into one another with a central story hub (think Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man) because he was worried that people would not be interested in the dry history of a land that didn’t exist. To tell this tale in a “Hobbit” style might make it more accessible to the everyday reader. However, he ran into the problem of how to make it work. He knew who Eriol was, and there were plans for him (which I believe will come to light in the last chapter of The Book of Lost Tales, part 2), but how does he get the surrounding characters into the work? The people who tell the tale? Well, he created things like Olórë Mallë, a sleep bridge that can get men (and only men apparently, as no Elves needed it because of their immortality) to different areas of space and time. He also created spaceships (literally ships that could sail across the sky) but decided to limit that to elevate a single character, Eärendil, to a godlike being as he sails his ship Vingilot across the sky.

These ideas were a means to an end, and he only used them to tell the story. He eventually realized that these plot devices were only taking away from the story instead of enhancing it, but his quandary was that to take them away removes all credence of the story that was being told. For this reason, I believe Tolkien took out the transition pieces with Eriol learning the histories.

That leads us right into Turambar because, as Ailios describes Úrin and how he knew Beren and his travails. Mavwin, Túrin’s mother and Úrin’s wife, decided that Túrin would be safer staying with Tinwelint, than he would up north with the threat of Melko.

Thus, Túrin’s story begins.

“Very much joy had he in that sojourn, yet did the sorrow of his sundering from Mavwin fall never quite away from him; great waxed his strength of body and the stoutness of his feats got him praise wheresoever Tinwelint was held as lord, yet he was a silent boy and often gloomy, and he got not love easily and fortune did not follow him, for few things that he desired greatly came to him and many things at which he laboured went awry (pg 74).”

Join me next week as we continue the tragedy of Túrin Turambar!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, Tale of Tinúviel, commentary

“In the old story, Tinúviel had no meetings with Beren before the day when he boldly accosted her at last, and it was at that very time that she led him to Tinwelint’s cave; they were not lovers, Tinúviel knew nothing of Beren bu that he was enamoured of her dancing, and it seems that she brought him before her father as a matter of courtesy, the natural thing to do (pg 52).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week, we’ll briefly cover Christopher’s commentary on The Tale Of Tinúviel and give some final thoughts on the story.

Much of what Christopher covers (Christopher is J.R.R. Tolkien’s son and editor. This book is posthumously published, and Christopher both compiled it and edited it) in his lengthy comments following the Tale of Tinúviel are the same or very similar to everything that I have covered in the previous Blind Reads, so we’ll speak about the most critical insights and give some context.

Before we jump into that, however, Christopher included a second draft (or at least pieces) of The Tale of Tinúviel just after the first edition and before his comments.

“This follows the manuscript version closely or very closely on the whole, and in no way alters the style or air of the former; it is, therefore, unnecessary to give this second version in extenso (pg 41).”

The most significant change that I noticed was the nomenclature. The forest’s name changed to Doriath, and the names Melian and Thingol are introduced here for the first time.

We also have the adjustment of Beren’s father from Egnor to Barahir and Angamandi to Angband. Most importantly, we first mention Melko as Morgoth (The Sindarin word for Melkor).

This last adjustment may seem like an alteration of monikers to streamline the narrative; however, knowing how The Silmarillion was published and the extensive lists of names, not to mention the number of names in each language many of the characters had, we know he did this intentionally.

Many people assume (and rightly so because the theory has become so ubiquitous) that Tolkien built a language (Elvish) and then developed a story and world based on that language. This theory makes a certain amount of sense because he was a linguist. Still, read these books (or, more importantly, Christopher’s annotation). You’ll understand that the world-building and the language came conjointly because of Tolkien’s desire to tell a fairy tale that would become England’s own. It was all supposed to start with this first story: The Tale of Tinúviel.

The names evolved because Tolkien was developing his language and the world the story took place in, and the names he originally used no longer made sense.

A prime example of this is in the second version of the story, “Beren addresses Melko as ‘most mighty Belcha Morgoth (pg 67).'” I’ll let Christopher explain:

“In the Gnomish dictionary Belcha is given as the Gnomish form corresponding to Melko, but Morgoth is not found in it: indeed this is the first and only appearance of the name in the Lost Tales. The element goth is given in the Gnomish dictionary with the meaning ‘war, strife’; but if Morgoth meant at this period ‘Black Strife’ it is perhaps strange that Beren should use it in flattering speech. A name-list made in the 1930s explains Morgoth as ‘formed from his Orc-name Goth ‘Lord of Master’ with mor ‘dark or black’ prefixed, but it seems very doubtful that this etymology is valid for the earlier period (pg 67).”

Tolkien was evolving and creating new languages for the Eldar and the Orcs, Dwarves, and Valar. Beyond that, he was developing dialects within these languages, so a Sindarin name would be different from a Noldoli name, which is where many people get confused about the number of names in The Silmarillion and how the rumor got started that Tolkien created the languages first and the world second. The above quote is the irrefutable proof (not to mention the extensive changes to The Lost Tales).

We can see the linguistic changes Tolkien is making, which in turn changes the story’s core, but there is some very interesting world-building that Tolkien has done in the augments between drafts.

The first example surrounds the Simarils; “The Silmarils are indeed famous, and they have a holy power, but the fate of the world is not bound up with them (pg 53).”

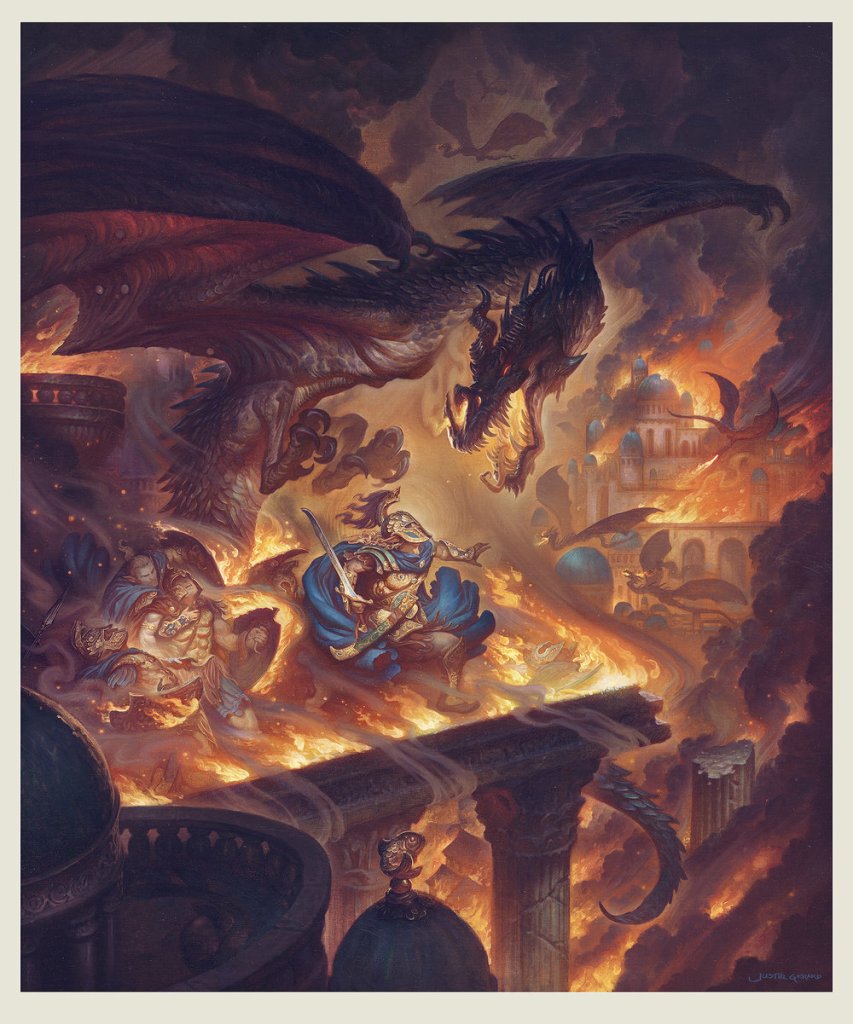

Tolkien understood the Maguffin (a plot device that sets the characters into motion and drives the story) early on. Still, his original intention was to tell the tale of two lovers, he and Edith, but in the names of Beren and Lúthien (Tinúviel). What he came to realize as he went through drafts and started to build the history of the world (this second version was also the first mention of Turgon the King of Gondolin because Tolkien had begun working on the story The Fall of Gondolin before he went back to the second draft of the Tale of Tinúviel), was that there needed to be a through line to bring the different tales together into one single history, rather than having a bunch of disparate short stories spattered throughout history. The Silmarils became that Maguffin. They grew in mystery and power in his mind. The tale of Valinor became the precursor and introduction to the power that the Silmarils contained so that they might tell a much larger story and have the whole of the world seeking the power they held (much like the One Ring in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings).

The Tale of Tinúviel is a fascinating addition to the Legendarium, but it does feel a little one-note beside its later counterpart, Of Beren and Lúthien. What is most interesting is the fairy tale manner in which Tolkien tells the tale. The first big bad we see is a cat who captures our hero and makes him hunt for them because they’re lazy cats. This anthropomorphized creature is a common theme in fairy tales, and Tevildo never truly poses a real threat, especially when Huan the Hound shows up. Then, when Tinwelint imprisons Tinúviel in a tall tower to keep her from going after her love, we get impressions of all the old Anderson Fairy Tales. In this early version, it is apparent that Tolkien was going for a fairy tale vibe (which in fact was his original intention before realizing that he wanted to make it more realistic, more gritty), but instead of eventually disneyfying it, he went deeper and darker and turned the tale into something bold and breathtaking, and seeing the transformation is something to behold.

We’ll take a week off before returning to the next story, “Turambar and the Foalókë.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.