Blind Read Through: J.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, The Link of Tinúviel

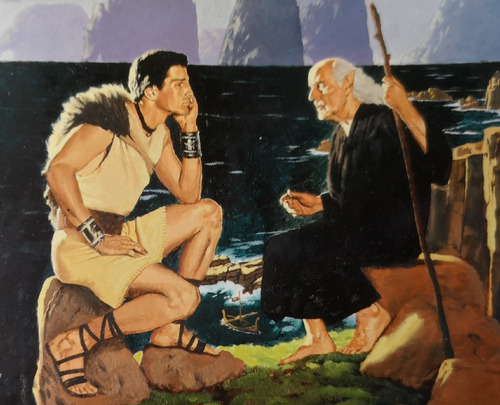

“Then there was eagerness alight, and Eriol told them of his wanderings about the western havens, of the comrades he made and the ports he knew, of how he was wrecked upon far western islands until at last upon one lonely one he came on an ancient sailor who gave him shelter, and over a fire within his lonely cabin told him strange tales of things beyond the Western Seas, of the Magic Isles and that most lonely one that lay beyond. Long ago had he once sighted it shining afar off, and after had he sought it many a day in vain (pg 5).“

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we begin The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, with the story of Middle-earth, which was closest to Tolkien’s heart.

This story is the earliest written tale in the Legendarium, even earlier than the tales of Ilúvatar and the Valar. Tolkien wrote the first manuscript in 1917 amid the Great War, and I have to imagine that he did so because he wanted a release from the horrors of the war happening around him.

Tolkien wrote the Tale of Tinúviel about his wife, Edith Tolkien, and it is both a beautiful homage and the seed from which all Middle-earth blossoms.

Those who know the story of Beren and Lúthien realize it is the tale of a man who falls in love with the most beautiful elven maid alive. Not only is she beautiful and sings like a nightingale, but she is a strong woman, a warrior, and a leader. Tolkien has been very forthright with the fact that Lúthien is, in fact, Edith, and the story of Beren seeing Lúthien singing and dancing in the forest was a call back to their walks in the dense woods of England when they first met.

This also means that the world of Middle-earth that Tolkien built would not be possible without Edith. Everything that happens in the Legendarium stems from this first origin (though doubtless there are poems written before this story, this was the first instance Tolkien wrote a new world through the lens of prose instead of poetry). Lord of the Rings even stems from this story. It echoes in Aragorn and Arwen, the Third Age’s version of Beren and Lúthien. There is even a passage in The Lord of the Rings compares Aragorn and Arwen to Beren and Lúthien.

This love story was at the core of everything that Tolkien wrote, and he built the greater Legendarium to support the story of his love for his wife. Though the tale grew beyond this conception, it remains the core of everything in Middle-earth.

Reviewing this tale will take multiple weeks, so to kick it off, I’d like to start with Eriol’s story and the link between where we left off in The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Also with where this book begins with The Tale of Tinúviel.

The tome takes up days after the events of Book of Lost Tales, part 1, with Eriol wandering in Kortirion, learning Elvish language and lore. One day as he is talking with a young girl and in a role reversal, she asks him for a tale:

“‘What tale should I tell, O Vëanne?’ said he, and she, clambering upon his knee, said : ‘A tale of Men and of childrren in the Great Lands, or of thy home – and didst thou have a garden there such as we, where poppies grew and pansies like those that grow in my corner by the Arbour of the Thrushes?'”

It may seem strange to call out this quote, but I do so because the passage ends here. Tolkien must have had the idea that Eriol would tell the history of Men, whereas the people of the Cottage of Lost Play would tell the story of the early times and the Elves.

Christopher gives a few different iterations of this interaction. Still, in every one of them, the story gets taken out of Eriol’s mouth as Vëanne interrupts him and begins the Lay of Lúthien (I.E., The Tale of Tinúviel).

I wonder if the intent was for Eriol to have his section of the book (which never actually happened) because Tolkien spends time here to set it up:

“‘I lived there but a while, and not after I was grown to be a boy. My father came of a coastward folk, and the love of the sea that I had never seen was in my bones, and my father whetted my desire, for he told me tales that his father had told him before (pg 5.)'”

The opening quote in this section talks about his “wanderings.” Before we get into the Tale of Tinúviel proper, there is also Eriol’s unwitting interaction with a Vala:

“‘For knowest thou not, O Eriol, that that ancient mariner beside the lonely sea was none other than Ulmo’s self, who appeareth not seldom thus to those voyagers whom he loves – yet he who has spoken with Ulmo must have many a tale to tell that will not be stale in the ears even of those that dwell here in Kortirion (Pg 7).'”

Eriol, to me, is a fascinating character because he has such a history, and he’s a mariner. If Tolkien created some stories from Eriol’s perspective, we might be able to see Middle-earth from a slightly different perspective, that of a sea-faring folk.

We know that all the history had come before this discussion. All of the first age (The Silmarillion) and the Second age (Akallabeth), and even the Third Age (The Lord of the Rings) came before Eriol’s time. So we can think of this soft opening in Kortirion as a Fourth Age, where Men (read Humans) run the world, the Elves have retreated to hidden Valinor, and much of the pain from the Dark Lord has disappeared, or at very least forgotten, from the world.

Join me next week as we start The Tale of Tinúviel!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, Final Thoughts

“Melko shalt see that no theme can be played save it come in the end of Ilúvatar’s self, nor can any alter the music in Ilúvatar’s despite. He that attempts this finds himself in the end but aiding me in devising a thing of still greater grandeur and more complex wonder:–for lo! through Melko have terror as fire, and sorrow like dark waters, wrath like thunder, and evil as far from the light as the depths of the uttermost of the dark places, come into the design that I laid before you. Through him has pain and misery been made in the clash of overwhelming musics; and with confusion of sound have cruelty, and ravening, and darkness, loathly mire and all putrescence of thought or thing, foul mists and violent flame, cold without mercy, been born, and Death without hope. Yet is this through him and not by him; and he shall see, and ye all likewise, and even shall those beings, who must now dwell among his evil and endure through Melko misery and sorrow, terror and wickedness, declare in the end that it redoundeth only to my great glory, and doth but make the theme more worth the hearing, life more worth the living, and the World so much the more wonderful and marvellous, that of all the deeds of Ilúvatar it shall be called his mightiest and his loveliest.”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we recap The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, and in doing so, speak about the more fantastic aspect of Middle-earth and Tolkien’s intention.

The Book of Lost Tales is an amalgam of Tolkien’s work throughout his life. Christopher has included some of his father’s earliest poems, scraps of notes stuck into notebooks, various illustrations, and books and books of re-writes to show the thought and care Tolkien put into the work.

John wanted to tell a fantastic story that would give people meaning. He wanted a new fairy tale that would anchor into our world and give people wonder and hope (and perhaps even give reasoning for things like The Great War).

Many critics have said that The Lord of the Rings is an allegory to Tolkien’s time in the war, and if you only read the book itself, it is easy to understand why. Tolkien, however, hated allegory and had often stated that he pulled inspiration from his time in the war, but there was no allegory there. That can be hard to swallow, especially when his fellow Inkling (a society of writers who met to critique and edit each other’s work), C.S. Lewis, thought allegory one of the greatest literary techniques.

The story produced in The Lord of the Rings was a work of love developed over many decades, but to create a work so deep and well established Tolkien wanted a robust history of the world, that history is what eventually became The Silmarillion.

But Tolkien, like many authors, wanted the history of the world to be a story in and of itself, so in the earlier iterations, we get the tale of Eriol, who in turn is told the story behind The Silmarillion.

The problem Tolkien ran into, however, was that history is difficult to tell in a story format. There are fantasies, records, and fairy tales told in the Silmarillion, but they come late in the book and feel more like what he would eventually write in The Lord of the Rings. The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, is Eriol learning instead about the Valar and how the Eldar (Gnomes in this earlier version) came into being. However, even in these earlier versions, we still need to catch minor differences with how Tolkien later decided to frame everything.

Facts, like the Maiar being the children of the Valar, the Eldar being Gnomes, and the sparse inclusion of Fëanor are stark differences to how the story eventually played out, and what is great about reading through this book was being able to read Christopher’s analysis (Tolkien’s son and editor) of where Tolkien tried to take the story, and where he decided to end up. This process is the magic of reading The Book of Lost Tales, part 1. Part 2, I’m sure, will have just as many quirks, but part 2 is where the stories that built the history of Mankind came into being. Stories like the Lays of Lúthien, the Tale of Túrin Turambar, and the Fall of Gondolin all take place in the second half of these histories. These tales inform our characters in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Beyond The Silmarillion, there is minimal mention of the Valar or Ilúvatar.

In Christopher’s sentiment, the first book is less interesting because it’s about the development of the world itself and not necessarily about the people; thus, it’s harder to give stakes because we know what will eventually happen.

Knowing all this, Ilúvatar is the most provocative being or concept in Tolkien’s oeuvre. Ilúvatar is God for this World (even though the Valar intermittently are called gods, Tolkien later stripped them of that title for The Silmarillion).

The quote to start this essay is a perfect example of the fallibility of gods in general. Tolkien was deeply religious, and I’m sure he wrote Ilúvatar to be Middle-earth’s Yahweh and much of the struggle and philosophy in Middle-earth is how to accept or deal with the concept of Death. Death is a “gift” given to Man when they are born, so they might make life more meaningful. Death was not a concept until Morgoth sang its theme into existence.

This path makes Melkor the most tragic character in the pre-history of Middle-earth because, as we see from the opening quote, he has no choice. Ilúvatar, as the master creator, knew every theme he wanted to put into the world, and Death, hate, and suffering would be part of existence.

Iluvatar created each Vala to inform specific parts of his themes, but themes were all they were, meaning that the Valar had free will over what theme they were given. Iluvatar created Melkor to suffer. He created him to be a Dark Lord because he knew that without a Dark Lord making people work for their freedom, they would take their lives for granted.

Tolkien didn’t write Allegory; he wrote philosophy. Death is a gift because we cannot appreciate light without darkness. We cannot fully appreciate life without death.

Come join me next week as we begin our foray into “The Book of Lost Tales, part 2,” the second book of the Histories of Middle-earth!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1; Gilfanon’s Tale

“Suddenly afar off down the dark woods that lay above the valley’s bottom a nightingale sang, and others answered palely afar off, and Nuin well-neigh swooned at the loveliness of that dreaming place, and he knew that he had trespassed upon Murmenalda or the “Vale of Sleep”, where it is ever the time of first quiet dark beneath young stars, and no wind blows.

Now did Nuin descend deeper into the vale, treading softly by reason of some unknown wonder that possessed him, and lo, beneath the trees he saw the warm dusk full of sleeping forms, and some were twined each in the other’s arms, and some lay sleeping gently all alone, and Nuin stood and marvelled, scarce breathing (pg 232-233).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we conclude The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, discussing symbolism and creative editing.

This chapter is more of Christopher’s musings on how his father was positioning the editing of the book rather than the tale itself. Gilfanon only has a few pages, and the rest of his story remains unfinished. In a more accurate sense, this is an early iteration of the chapter in the Silmarillion “Of Men.”

The origin of Men for Tolkien was a difficult thing to tackle. Christopher tells us that there were four different iterations throughout the process of coming up with the concept. Tolkien ended up significantly cutting down the chapter to be what it eventually became, which was relatively uninspired and just about as long as Gilfanon’s tale. One has to wonder if the weight of the linchpin of his mythology was so great that the chapter says, “They wake,” and then moves on.

Gilfanon’s tale tells of one of the Dark Elves of Palisor, Nuin. Nuin is restless and curious about the world, so he ventures out to experience it and comes across a meadow that holds The Waters of Awakening and humans sleeping near it (described in the quote above).

Nuin then heads back home and tells a great wizard who ruled his people about the humans sleeping by the waters and “Then did Tû fall into fear of Manwë, nay even of Ilúvatar the Lord of All (pg 233).” because of this fear he turned to Morgoth, and learned deeper and darker magic from him.

From what Christopher tells us, each version of the story Tolkien worked on evolved, and eventually, Tû, the Wizard, was cut from the Silmarillion. Tolkien cut nearly all mention of the elves who went to Morgoth’s side from the main context. There are only a few mentions of thralls throughout the main storyline.

One has to wonder if this was Tolkien’s decision that the Elves themselves shouldn’t turn to the “dark side.” Even though the Noldor did some heinous things in Swan Haven, they ultimately did it out of a hatred that burned so deep for Morgoth’s blood that they wouldn’t let anyone stand in their way.

The inclusion of Tû, even if he is more of a fay creature than Elvish, creates issues with Tolkien’s history. So he took the name Tû out of the book to keep the Elvish lines as “pure” as possible, but the character of Tû is still in the book, AND I believe he plays a much larger part.

Remember that Tû is described as a fay wizard, and the only wizards in the history of Eä were the Istari (of which Saruman and Gandalf were a part). The Istari were Maiar, otherwise known as lesser Valar. In general, they were servants to the Valar (in The Book of Lost Tales, many of them were the children of the Valar) and aided in bringing the will of Ilúvatar into being.

The Istari were sent to Middle-earth in the Second Age to assist the people of that land in their fight against Sauron. They could turn into a mist and travel vast distances to reach their destination – something Sauron did after the Drowning of Númenor.

So this early Wizard trained in the dark arts by Morgoth must be an earlier version of Sauron himself. Sauron, after all, assisted the Elves in the creation of the Rings of Power, was known to be a wizard himself, and eventually picked up Morgoth’s mantle when the Dark Lord was locked behind the Door of Night.

The other exciting portion of the quote I’d like to discuss before closing thoughts is the mention of Nightingales and the Coming of Man in the opening quote.

Nightingales generally have a long history of symbolism, more specifically revolving around creativity, nature’s purity, or a muse. All of these aspects center around virtue and goodness.

Tolkien is using the nightingale song to indicate a more artistic and virtuous age because when Nuin followed the song, he came across the sleeping children by the Waters of Awakening.

Tolkien’s tale is ultimately (as we’ve covered many, many times) about Man (read that as Humans), so everything we have read thus far has been pre-history, which is also why Christopher separated The Book of Lost Tales into a part 1 and a part 2. Part 1 is about how the world became what it was. Now that we have humans, Part 2 is about the rest of the first age and carries what Christopher calls “all the best stories.”

So the nightingale indicates to the fay and the Eldar (Gnomes in The Book of Lost Tales) that there will be a shift in the world, and they will no longer be the focal point. This also spooks Nuin because, at the moment, by the Waters, he sees that his time will come to a close eventually, even though he’s immortal. The world was not built for him but for the new creatures just now waking into the world.

Join me next week as we have some final thoughts on The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, before jumping into The Book of Lost Tales, part 2, the week after!

Blind Read Through: J.R.R. Tolkien; The Book of Lost Tales, part 1; The Hiding of Valinor, part 2

“Thereat did Tulkas laugh, saying that naught might come now to Valinor save only by the topmost airs, ‘and Melko hath no power there; neither have ye, O little ones of the Earth’. Nonetheless at Aulë’s bidding he fared with that Vala to the bitter places of the sorrow of the Gnomes, and Aulë with the mighty hammer of his forge smote that wall of jagged ice, and when it was cloven even to the chill waters Tulkas rent it asunder with his great hands and the seas roared in between, and the land of the Gods was sundered utterly from the realms of the Earth (pg 210).”

Welcome back to another Blind Read! This week we conclude the tale of The Hiding of Valinor, as Tolkien delves deep into how he wanted to create the world.

This week is a perfect example of what a plotter writer does to create their world. Speaking from my own experience, worldbuilding is one of the hardest things to do as a writer because you want to thread the needle between creating a full, lush, believable world and muddling that same world with incessant useless details.

The Book of Lost Tales was never an actual book but a collection of notebooks, poems, anecdotes, and loose scrap paper Tolkien used to create his world over decades. From The Great War’s trenches to The Hobbit’s eventual publication, he filtered these notes to make what would later become The Silmarillion.

The Book of Lost Tales holds all the different cockamamie concepts which could comprise a fairy world. Christopher tells us many times that some of the detail has been cut because the text was re-written so many times (potentially multiple times in pencil and erased until Tolkien had a version he liked enough to write it out in pen… which many times was still not the last iteration)

What I’d like to cover this week for some fun differences is the detail Tolkien went to explain how the world came into being, which he later cut because much of it has little or nothing to do with the actual world.

The first instance I’d like to cover is the minutia of the Sun and the Moon route.

The Valar have a council for multiple pages concerning how they would go about hiding Valinor: “Nonetheless Manwë ventured to speak once more to the Valar, albeit he uttered no word of Men, and he reminded them that in their labours for the concealment of their land they had let slip from thought the waywardness of the Sun and the Moon (pg 214).”

We’ve previously discussed the path the Sun and the Moon had taken because of where different Valar (and Ungoliant) took up their residence. Still, they worry about “removing those piercing beams more far, that all those hills and regions of their abode be not too bringht illumined, and that none might ever again espy them afar off (pg 214).”

Yavanna worried that the change in the movement of the light from either the Sun or the Moon could create strife in the world, so Ulmo told them they had nothing to worry about. The Ocean is so large that the Valar don’t even fully comprehend its magnitude, nor have they ever interacted with any of the creatures of the world, “but Vai runneth from the Wall of Things unto the Wall of Things withersoever you may fare…ye know not all wonders, and many secret things are there beneath the Earth’s dark keel, even where I have my mighty halls of Ulmonan, that ye have never dreamed on (pg 214).”

Ulmo tells the other Valar they have nothing to worry about because the world is so vast that Ilúvatar’s children could never find them after centuries of looking. To counteract that worry, Ulmo and Aulë say they will build ships that can sail into Valinor so that Men and Eldar can come home.

The way Tolkien writes it, it’s unclear whether he means for the “children” to come home to heaven, or something a little more fairy tale-esque, like the Elysian Fields of Greek Mythology fame or Valhalla of the Norse. In any case, it’s a clunky bit of logic. I find it fascinating to see how Tolkien began devising the world, but I agree with Christopher that this level of detail is unnecessary for the greater story.

Finally, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention one more cut—the creation of time.

“‘Lo, Danuin, Ranuin, and Fanuin are we called, and I am Ranuin, and Danuin has spoken.’ Then said Fanuin: ‘And we will offer thee our skill in your perplexity – yet who we are and whence we come or whither we go that we will tell to you only if ye accept our rede and after we have wrought as we desire (pg 217).'”

Instead of having time be attributed to the movement of the Sun and the Moon, Tolkien went much more mythological and created Tom Bombadil-type characters to create a way to understand the passing of time.

Danuin is the anthropomorphized concept of a Day, Ranuin is Month, and Fanuin is Year. They appear out of nowhere and approach the gods, offering gifts that later become this understanding of the passing of time.

Tolkien tells this tale at the end of the Hiding of Valinor because it is meant to be a passage of responsibility of the world to the next generation, the Eldar. The Valar are hiding away in Valinor, and the coming of these brothers created the concept of an “age.”

Before this moment, time didn’t exist, so the Valar just went about doing what they thought necessary, but this is also why the Eldar are immortal as well because they were born before time existed, men were born just after, so they were beholden to its aspect:

“Then were all the Gods afraid, seeing what was come, and knowing that hereafter even they should in counted time be subject to slow eld and their bright days to waning, until Ilúvatar at the Great End calls them back (pg 219).”

The brothers bestow this curse (or gift) of time and then say, “our job is done!” and peace out.

It’s curious how the brothers came into being, seeing as the Valar created everything in the world, but then again, there are deeper and unknown places in the world that others don’t know about, so this is a slight possibility; it’s just a clunky and unnecessary addition and one that even Christopher is glad he eventually cut:

“The conclusion of Vairë’s tale, ‘The Weaving of Days, Months, and Years’, shows (as it seems to me) my father exploring a mode of mythical imagining that was for him a dead end. In its formal and explicit symbolism it stands quite apart from the general direction of his thought, and he excised it without a trace (pg 227).”

Even Tolkien creates things where he looks back at it and realizes how out of sorts they are. Stand proud when you find mistakes because you know you FOUND them!

Join me next week as we jump into the last chapter of The Book of Lost Tales, part 1, “Gilfanon’s Tale: The Travail of the Noldoli and the Coming of Mankind.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.